When HSBC Bank placed posters at airports such as Gatwick and Dubai in 2013 as part of its global campaign „The future is full of opportunity” – showing a fingerprint, a QR code, and the provocative slogan „Your DNA will be your data” – the message was unambiguous: the future will be personal, perhaps unsettlingly personal. The bank sought to position itself as a forward-looking company that addresses digitalization, artificial intelligence, sustainability, and genetics head-on.

The slogan seemed ambiguous – both a promising vision and an alarming prospect. Critics immediately sounded the alarm: your DNA becomes readable, analyzable, and digitally accessible – an open book about ancestry, health risks, perhaps even personality traits – comparable to biometric data such as fingerprints or facial scans. What was once considered the most intimate aspect of a person is now becoming a file: machine-decipherable, potentially storable, possibly tradable. The human being is reduced to information – „bits and bytes” that could be processed, sold, or misused.

Who owns the rights to your genetic data? And who has access to it? You yourself? The company that conducted the test? Do surveillance, data leaks, and misuse by state and private actors reach a new dimension as a result? The vision of designer babies, genetic selection, and personalized advertising based on biological markers raises serious ethical questions. Will progress ultimately be paid for at the price of individual freedom?

However, the biotech revolution has long since gained tremendous momentum, and more and more voices recognize the enormous potential of this development. The March 2024 e-book edition of HSBC Bank Frontiers – Biotech – Five Big Ideas Shaping the Biotech Revolution states:

„The idea of exploiting nature for goods and services is nothing new. But the practice entered its modern era in the 1970s, with the advent of genetic engineering and the establishment of the first biotech companies. This brought together science and business like never before, and the influx of capital galvanized research and development efforts.

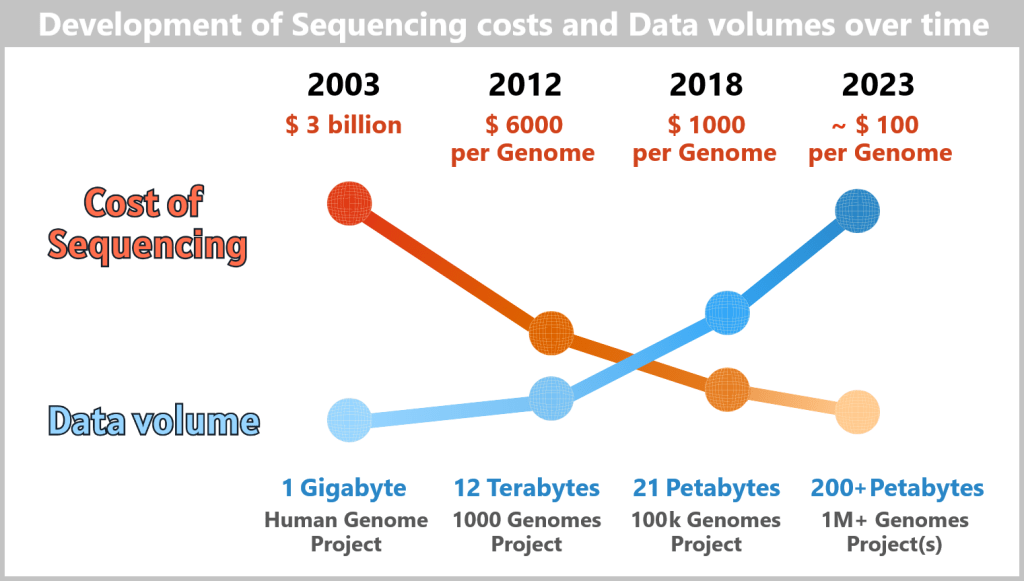

Over the three decades that followed, the field was accelerated by breakthrough devices such as DNA sequencers and synthesizers, and biology itself slowly morphed into a computational, data-driven discipline. Following the turn of the millennium, as researchers successfully charted ever greater regions of the human genome, and the cost of sequencing that genome rapidly declined – from around $100 million in 2001 to less than $1,000 today – the potential of biotech to transform our lives has become electrifyingly apparent.

Over the past few years, the possibilities unlocked by biotech advances – from treating genetic diseases to de-extincting animal species – have been enlarged by progress in complementary fields such as artificial intelligence. This has underpinned a coming-of-age moment in this space.“

Nowhere else do benefits and risks collide as directly as in personalized – or precision-based – medicine. Its goal is to use individual genetic and biological information to refine diagnoses, personalize therapies, and detect diseases at an early stage. The vision is promising: fewer side effects, better chances of recovery, more effective prevention – medicine tailored to the individual.

But here, too, what is celebrated as medical progress brings societal, legal, and ethical challenges:

- Who decides which genetic data are relevant?

- What role does access to these technologies play – does it exacerbate social inequalities?

- And how can discrimination, for example through genetic scoring by insurance companies or employers, be prevented?

Between the hope for individual healing and the fear of collective disempowerment lie fundamental questions: Does access to one’s biological data empower the individual – or expose them? Is personalized medicine a blessing – or the beginning of an era of subtle dehumanization?

Hence the crucial question is: Is personalized medicine the promised ascent into heaven – or the plunge through the gates of hell?

This blog post invites readers to consider personalized medicine in all its complexity – beyond hype or alarmism. It is deliberately aimed as well at non-experts who wish to engage critically with the opportunities, risks, and ethical tensions of this medical revolution.

📑Table of Contents

1. Conceptual Classification and the Fundamental Paradigm

2. Driving Forces – Between Vision and Reality

3. The Future of Medicine Begins in the Cell

3.1. How Biology and Technology Come Together

3.2. Data, Responsibility, and the Bigger Picture

4. From DNA to Knowledge – A High-Speed Train of Innovation

4.1. DNA – The Blueprint of Life

a) DNA: The Molecular Information Archive of Life

b) From Code to Protein: How Instructions Become Reality

c) Epigenetics & Non-coding DNA: The Conducting Team of Our Genome

d) The Hidden Control Center: What Non-coding DNA Regulates

e) When the Operating System Makes You Sick

f) Open Mysteries in Research

g) The True Magic of Genes

4.2. Genetic Variation and Its Consequences

4.3. Genome Sequencing: Key to Individual Genetic Material

a) The Journey of DNA: From Umbilical Cord Blood to Genetic Information

b) Three Directives for Gene Diagnostics: WGS, WES, and Panel

4.4. Methods of Genome Sequencing

4.4.1. Method 1: Copying with Fluorescent Dye

a) Sanger Sequencing

b) Illumina Technology

c) Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing

4.4.2. Method 2: High-Tech Tunnel – Electrically Scanning DNA

a) Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

4.4.3. Genome Sequencing – Technologies Compared

a) Throughput vs. Usability – Quantity Does Not Always Equal Quality

b) Cost-Effectiveness – Cost per Base vs. Cost per Insight

c) From Sample to Result – How Quickly Does the Whole Genome Speak?

d) Clinical Applications – Which Technology Fits Which Purpose?

e) AI as Co-Pilot – Automation Without Relinquishing Responsibility

f) Comparison Table: Sanger, Illumina, PacBio, ONT

g) Key Takeaways: Between Maturity and Routine

4.5. Genome Sequencing: The Next Technological Leap

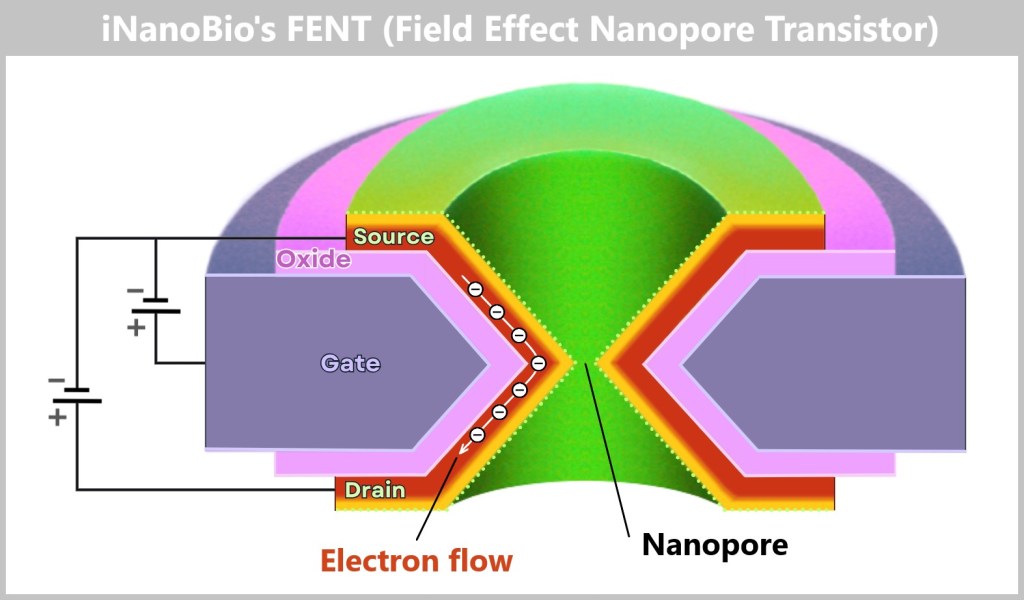

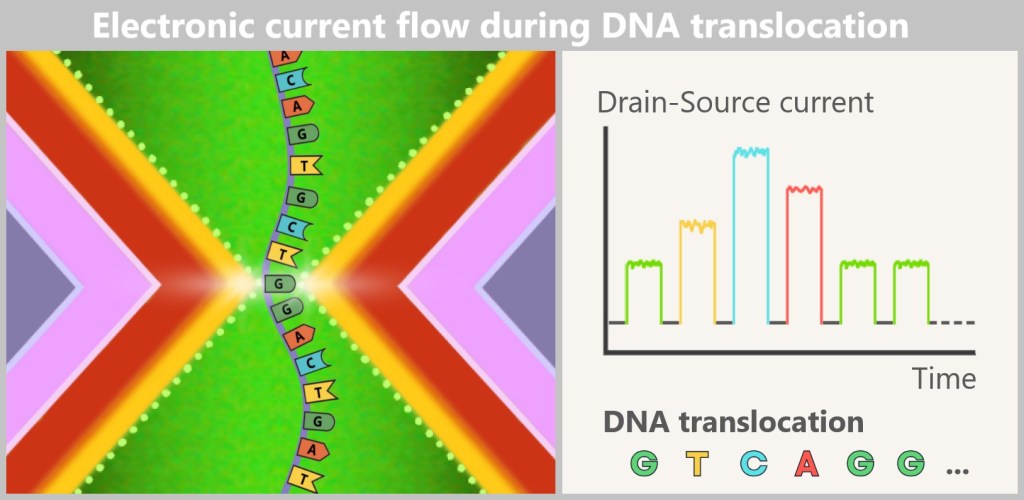

a) FENT: How a Microchip Is Revolutionizing DNA Analysis

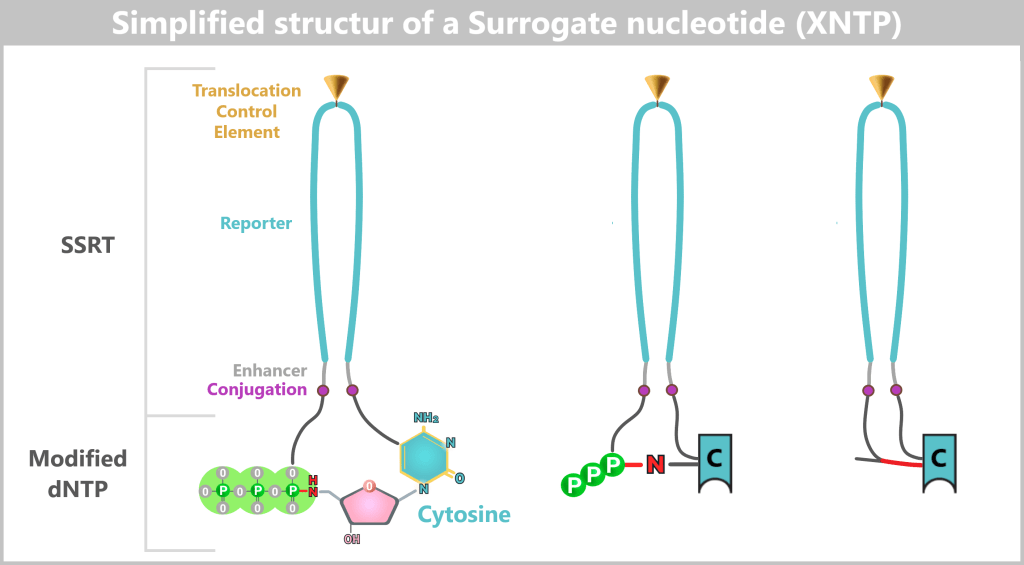

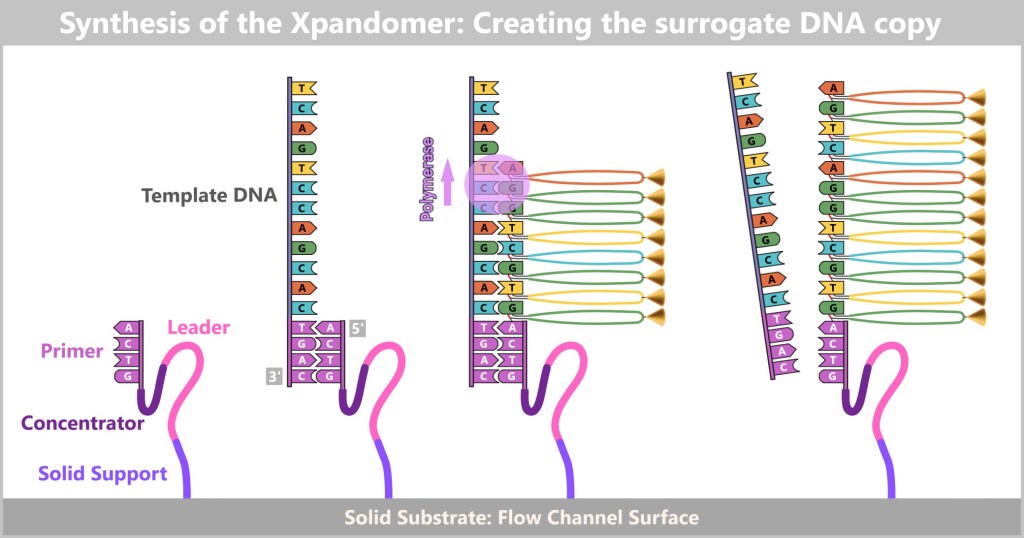

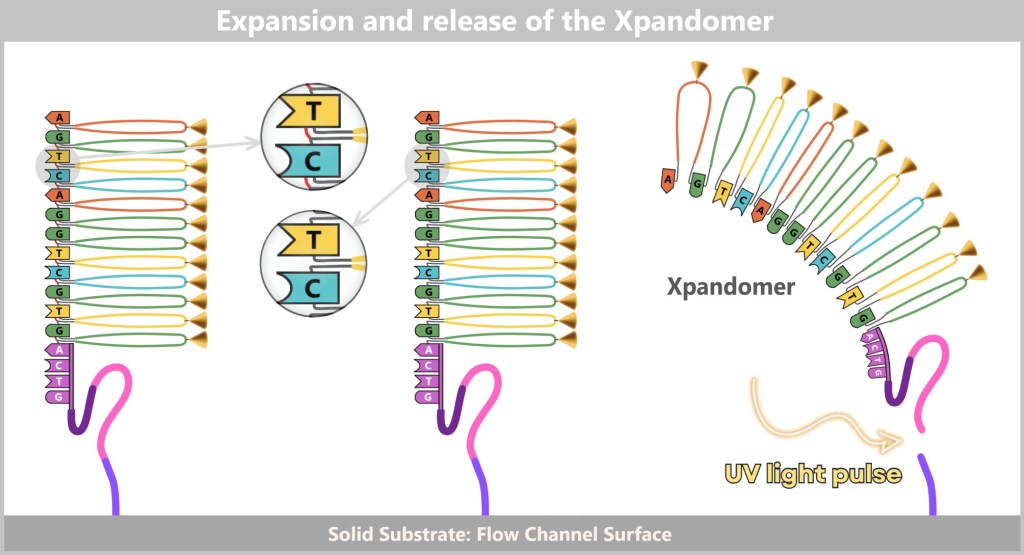

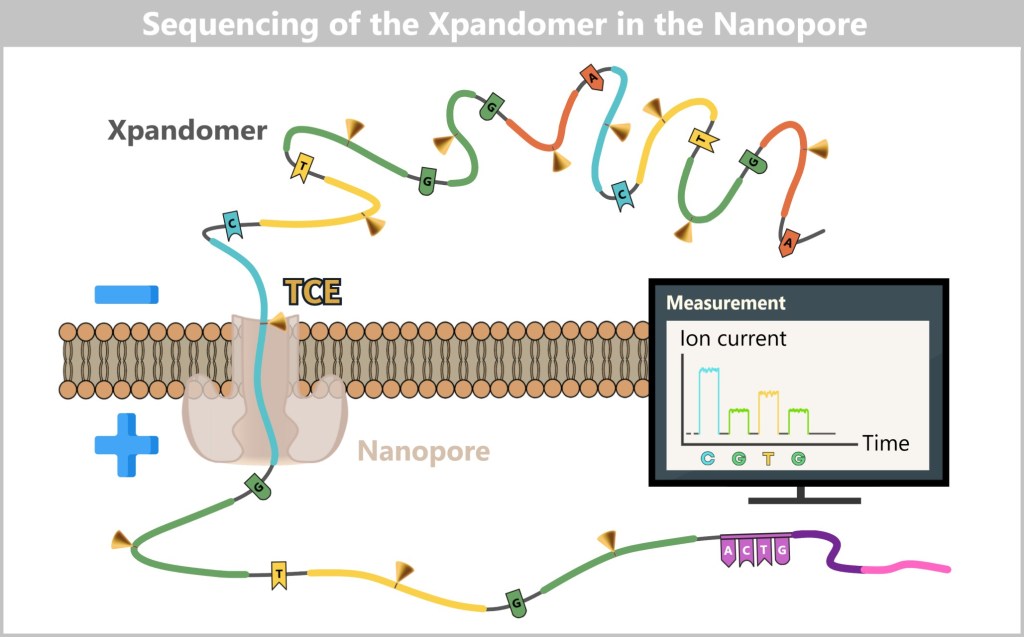

b) SBX: When DNA Stretches to Be Understood

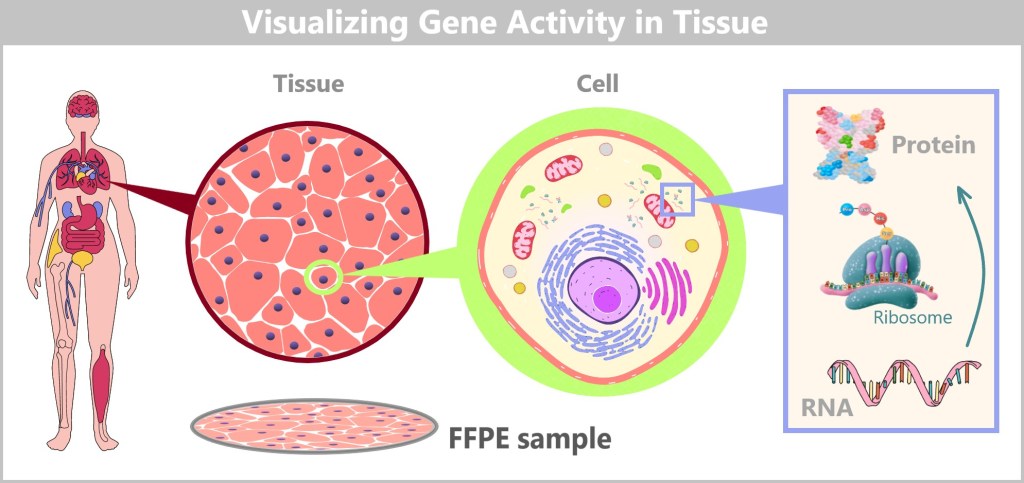

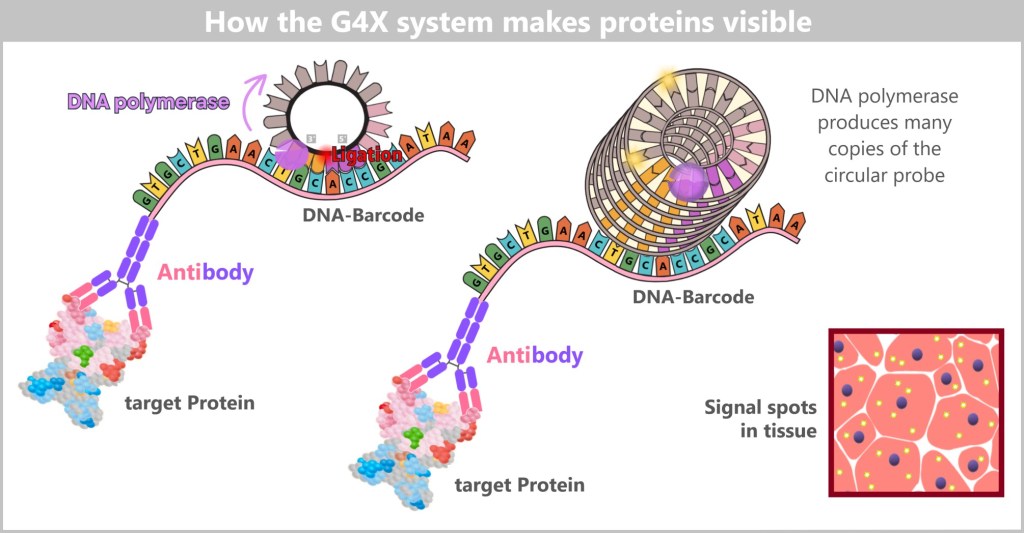

c) The G4X System: From the Genetic Recipe to the Spatial Atlas of the Cell

4.6. From Code to Cure – Bioinformatics as the Key to Tomorrow’s Medicine

4.6.1. From the Genetic Code to Computer-Aided Genome Analysis

4.6.2. Modern Bioinformatics – The Digital Toolbox of Biology

5. A Success Story

6. A Look into the Future: The Synthetic Human Genome Project

7. Personalized Medicine and Smart Governance

7.1. Power, Governance, and Smart Governance

7.2. Governmentality

7.3. Personalized Medicine as a Catalyst for Biomolecular Governmentality

7.4. The Global Trend: Worldwide Biomolecular Governmentality

7.5. Conclusion: The Global Ambivalence of Biomolecular Power

8. Epilogue

1. Conceptual Classification and the Fundamental Paradigm

The development of modern medicine toward tailored treatments is often described using terms such as „personalized medicine”, „individualized therapy” or „precision medicine”. But what exactly do these buzzwords mean?

Personalized medicine is currently considered one of the most popular terms – catchy like a marketing slogan. It carries the promise of tailoring therapies to each individual: to their genes, their lifestyle, their biology. Accordingly, the term is frequently used in the media and public debate.

Individualized therapy sounds less glamorous but conveys a similar idea: the adjustment of medications or dosages to the needs of individual patients. This term is used primarily in clinical practice.

Finally, precision medicine is the most sober of the three terms – a technical term that dominates research laboratories and scientific publications. It emphasizes the data-driven approach: algorithms, genetic analyses, and biomarkers determine which therapy works for which patient group. This is the language of science.

But regardless of which term is used, they all represent a paradigm shift: moving away from standardized procedures toward medicine that focuses on the biological uniqueness of each individual.

2. Driving Forces –Between Vision and Reality

The driving forces behind personalized medicine are diverse and closely interconnected. On one hand, there are scientific and technological developments that have enabled enormous progress in recent decades: new methods to read genetic material quickly and accurately, powerful data analysis through artificial intelligence, and the availability of large biomedical datasets. These technologies form the foundation for recognizing individual differences between patients and leveraging them medically.

On the other hand, social and political impulses act as accelerators of this transformation. Public health programs, targeted research funding, strategy papers from international health organizations, and specific legislative initiatives actively drive the integration of personalized medicine into healthcare practice. Increased health awareness among the population, as well as growing expectations for individualized treatment options, further reinforce this trend.

Personalized medicine is therefore not merely a product of technological feasibility, but emerges at the intersection of innovation, politics, and societal demand.

A current example of the practical implementation of this development comes from the United Kingdom: under a new 10-year plan, every newborn is to undergo a DNA test. The so-called whole-genome sequencing will screen for hundreds of genetically linked diseases – with the aim of detecting potentially life-threatening conditions early and preventing them in a targeted manner. According to British Health Secretary Wes Streeting, the goal is to fundamentally transform the National Health Service (NHS): moving away from mere disease treatment toward a system of prediction and prevention. Genomics – the comprehensive analysis of genetic information – will serve, in combination with artificial intelligence, as an early warning system.

„The revolution in medical science means that we can transform the NHS over the coming decade, from a service which diagnoses and treats ill health to one that predicts and prevents it“, said Streeting. The vision: personalized healthcare that identifies risks before symptoms even appear – thereby improving quality of life and alleviating pressure on the healthcare system.

But as convincing as this vision may sound, there are also cautionary voices coming from the scientific community. For example, geneticist Prof. Robin Lovell-Badge from the Francis Crick Institute warns against underestimating the complexity of genomic data. Not only is technical expertise required for data collection, but above all qualified personnel who can communicate the information obtained in a responsible and comprehensible manner. Data alone does not constitute a diagnosis – what is crucial is its meaningful and patient-oriented interpretation.

What does it concretely mean to rethink medicine?

The real revolution is taking place in laboratories and data centers, where the building blocks of personalized medicine are being developed. The following chapters take you behind the scenes, step by step, and reveal the key technologies needed to bring personalized medicine from concept to clinical practice.

3. The Future of Medicine Begins in the Cell

3.1. How Biology and Technology Come Together

Our bodies consist of billions of cells – tiny, specialised units that work together day after day to enable health and life. In every single cell, countless processes occur that are precisely coordinated with one another. These cellular mechanisms are crucial for understanding health, disease, and the development of new, targeted therapies.

One central mechanism is energy production: cells convert nutrients and oxygen into ATP (adenosine triphosphate) – the body’s „energy currency”. Without ATP, no cell could function, no muscle could move, no thought could arise.

At the same time, cells continuously produce proteins – based on genetic information. These complex molecules perform essential tasks in the body, serving as chemical catalysts, signaling molecules, structural components, or transporters.

Cellular cleaning and renewal are also vital: processes such as autophagy break down and recycle damaged cellular components – an internal waste disposal system that can help prevent diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

For cells to work together in a coordinated way within the body, they need functioning signaling pathways – they „communicate” with one another through chemical messengers. This cell communication controls when cells should grow, rest, or respond to changes.

Another key process is cell division – essential for growth, wound healing, and tissue renewal. At the same time, DNA repair mechanisms ensure that errors in the genetic material are corrected. If this fails, apoptosis, the programmed cell death, takes over to limit potential damage.

All these mechanisms run in the background – constantly and with high precision. However, if one of these processes is disrupted, it can lead to serious diseases such as cancer, autoimmune diseases or metabolic disorders. This is exactly where personalized medicine comes in. It uses state-of-the-art technologies to better understand these cellular processes and influence them in a targeted manner.

Thanks to genome sequencing (for example through „next-generation sequencing”), it is possible to identify genetic alterations that influence protein production or repair mechanisms.

Biomarker analyses (the examination of specific molecules) in blood, tissue, or other bodily fluids reveal whether certain signaling pathways are over- or underactive – and help predict individual disease progressions or select appropriate therapies.

Single-cell analysis makes it possible to visualize differences even between individual cells – for example, in a tumor, where some cells respond to therapy and others do not. This enables more precise treatment.

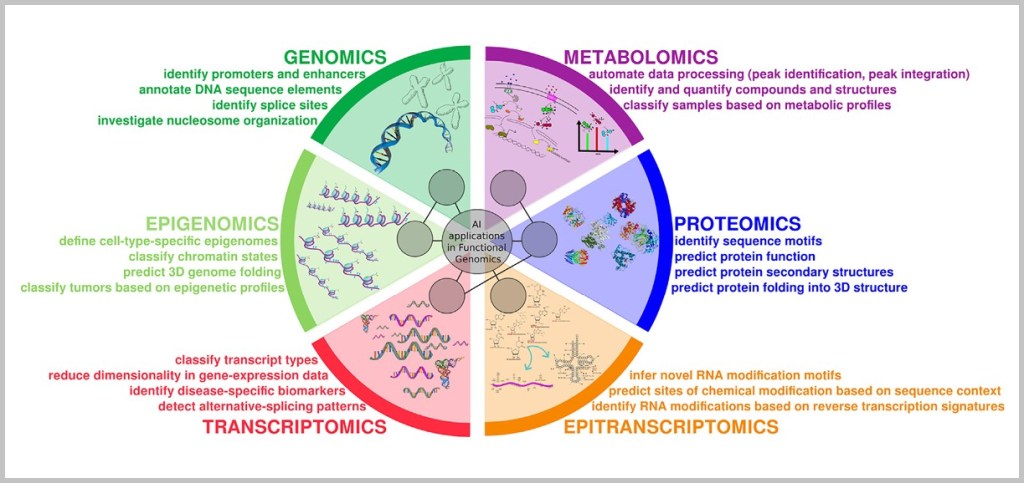

Proteomics (the analysis of all proteins in a cell) and metabolomics (the analysis of metabolic products) also provide a current picture of how active specific cellular mechanisms really are – for example, whether a cell is stressed, has sufficient energy, or is in the process of dividing.

Artificial intelligence (AI) helps analyze these vast amounts of data and identify patterns – for example, which combination of cellular disorders is typical for a particular type of cancer. Digital health data (such as from wearables) complement this picture in daily life and enable precise long-term monitoring.

Even new therapeutic approaches are based on understanding cellular processes: gene therapies and CRISPR-based gene editing target the DNA to correct faulty mechanisms. In organoids – mini-organ models in the lab – drugs can be tested directly on patient-specific cell models, without any risk to humans.

Modern technologies now reveal what was previously hidden: how cells work, what causes imbalances in disease – and how to intervene in a targeted manner. This has given rise to individualized medicine that is no longer based on conjecture, but on measurable biology.

This new precision brings not only opportunities, but also new responsibilities.

3.2. Data, Responsibility, and the Bigger Picture

The complexity of these cellular processes is directly reflected in the complexity of personalized medicine: the more precisely we understand the intricate processes and interactions in our cells, the more targeted – but also more demanding – diagnosis and therapy become. This new precision requires new technologies, new ways of thinking, and a deep biological understanding. At the same time, it opens the door to more effective, sustainable, and tailored treatment concepts.

However, the more targeted and profound these interventions become, the greater the responsibility – and the challenge of identifying and controlling undesirable long-term effects or side effects at an early stage. Particularly in the case of innovative procedures such as gene therapy or immunomodulation, it is important to carefully weigh up the benefits against the potential risks. Personalized medicine therefore requires not only precision, but also foresight.

A central element of this foresight is the availability of personal health data – not only in individual cases, but on a large scale.

Only by combining individual data with population data is it possible to understand biological processes in detail, predict disease progression and develop personalised therapies. Genetic information, laboratory values, imaging data and digital everyday measurements provide clues as to how cellular mechanisms work in a specific person – and how they vary in others.

To interpret these individual patterns medically, large datasets are needed for comparison. Only in this way can AI systems detect complex relationships that escape the human eye – such as rare genetic variants, molecular risk constellations, or unexpected therapy effects. The rule here is: the larger and more diverse the data base, the more reliable the models – especially when they are continuously enriched with new information.

However, this progress can only be achieved if people are willing to share their health data – and can trust that it will be used securely and responsibly.

The future of medicine begins where all life originates: in the cell. But its success depends on the interplay of three forces: technological innovation, scientific depth – and ethical responsibility.

4. From DNA to Knowledge – A High-Speed Train of Innovation

How genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis are revolutionizing medicine

4.1. DNA – The Blueprint of Life

a) DNA: The Molecular Information Archive of Life

b) From Code to Protein: How Instructions Become Reality

c) Epigenetics & Non-coding DNA: The Conducting Team of Our Genome

d) The Hidden Control Center: What Non-coding DNA Regulates

e) When the Operating System Makes You Sick

f) Open Mysteries in Research

g) The True Magic of Genes

4.2. Genetic Variation and Its Consequences

4.3. Genome Sequencing: Key to Individual Genetic Material

a) The Journey of DNA: From Umbilical Cord Blood to Genetic Information

b) Three Directives for Gene Diagnostics: WGS, WES, and Panel

4.4. Methods of Genome Sequencing

4.4.1. Method 1: Copying with Fluorescent Dye

4.4.2. Method 2: High-Tech Tunnel – Electrically Scanning DNA

4.4.3. Genome Sequencing – Technologies Compared

4.5. Genome Sequencing: The Next Technological Leap

4.6. From Code to Cure – Bioinformatics as the Key to Tomorrow’s Medicine

Imagine standing on a train platform and watching a train rush by at such speed that you can barely make out the image in the window. This is how many people perceive developments in personalized medicine: technologies are advancing at breakneck speed, terms seem abstract – and yet there is a common thread running through it all: the human genome.

As diverse as modern approaches may be – from organoids and CRISPR-based gene editing to RNA-based medicines – at the center lies the human genetic blueprint. Today, genome sequencing forms the foundation of many diagnoses and therapeutic decisions. It reveals which genetic alterations trigger diseases, which signaling pathways are affected – and where targeted interventions might be possible.

What once cost billions and took years can now be done in a matter of days: the entire human genome can be decoded. But the sequence alone does not constitute a diagnosis. The sequence of three billion base pairs only has medical value once it is understood – and this is where the real challenge begins.

Bioinformatics enters the stage: an interdisciplinary field that combines mathematics, computer science and biology to derive patterns, risks and treatment options from raw data. It is the real bottleneck of personalized medicine – because it determines whether genetic variants are considered harmless, risky or disease-causing.

Individual sequences are compared with international reference databases, algorithms analyze millions of genetic variants, and learning systems model the complex interplay of genetics, environment, and metabolism.

This process is highly complex – and at the same time essential. Only computer-assisted evaluation makes DNA medically usable. There is an inseparable symbiosis between genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis: the sequence provides the data, the analysis provides the understanding. Without it, DNA remains a mere string of letters.

This is precisely why the following sections focus on the crucial question:

What does it mean to decode the genome – and to truly understand it?

What conclusions are possible – and where are their limits?

For anyone who wants to understand the future of medicine, it is essential to know how we read the human genome today – and how we are learning to interpret it.

The high-speed train of innovation has long since departed. Anyone who wants to ride along must understand where it is headed.

4.1. DNA – The Blueprint of Life

To embark on this journey, it is worth taking a brief look at the molecular foundations: how our DNA becomes a blueprint, how proteins are formed from it via the intermediate step of RNA, and how epigenetics fine-tunes these processes. Only this foundation makes it possible to understand what is actually happening when we decode the genome.

a) DNA: The Molecular Information Archive of Life

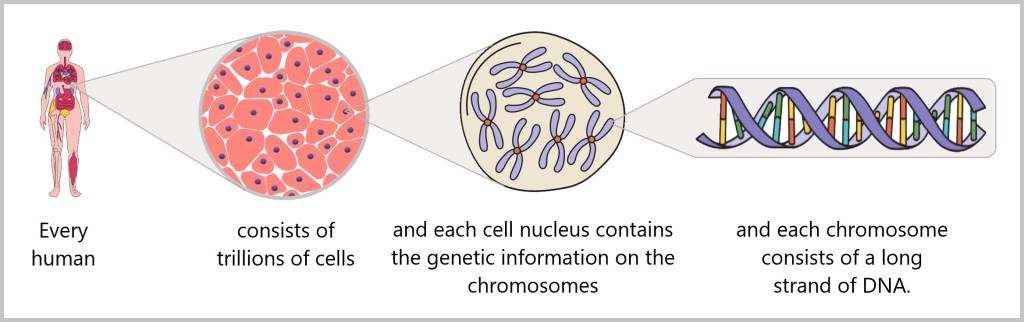

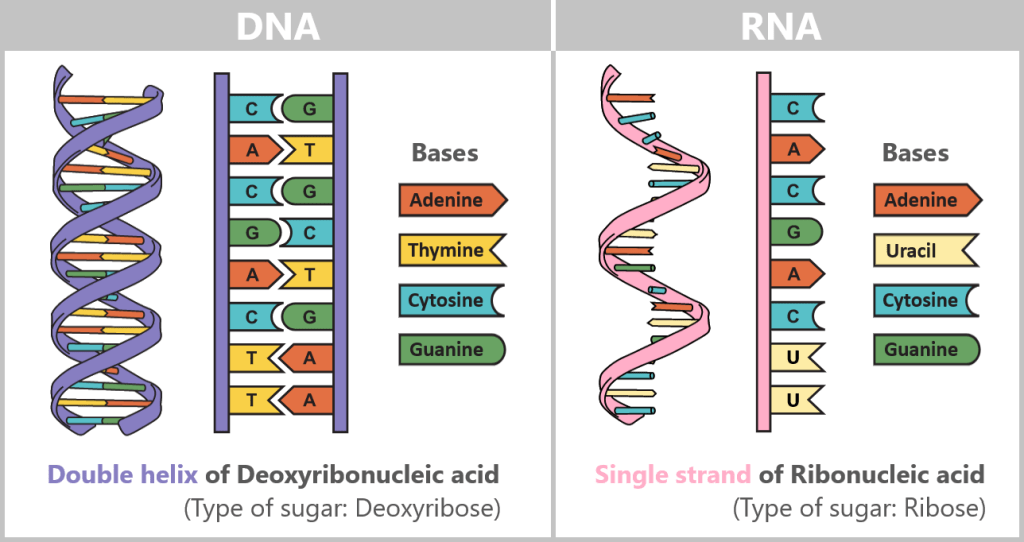

In every cell of our body lies a carefully packaged and astonishing molecule: DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). It contains the complete blueprint and operating instructions of our body – a molecular archive of life’s information.

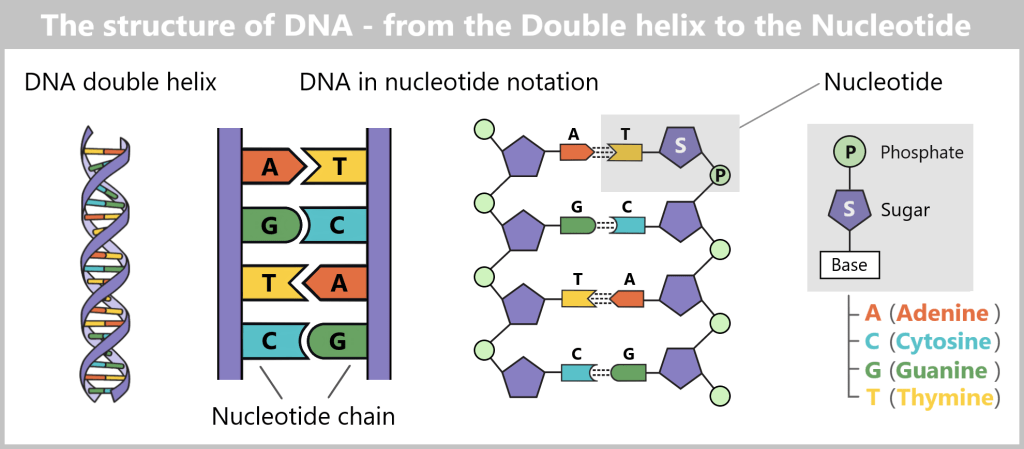

Structurally, it resembles a spiral-shaped rope ladder: two sugar-phosphate chains form the sides, with the „rungs“ – the bases adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T) – in between. They always pair up according to fixed rules: A with T, C with G. This complementary bond makes each strand a template for the other – a molecular backup system.

If you unravel the DNA from a single cell, it measures around two meters – with a diameter of just a few millionths of a millimeter. Life therefore literally hangs on a wafer-thin but astonishingly long thread.

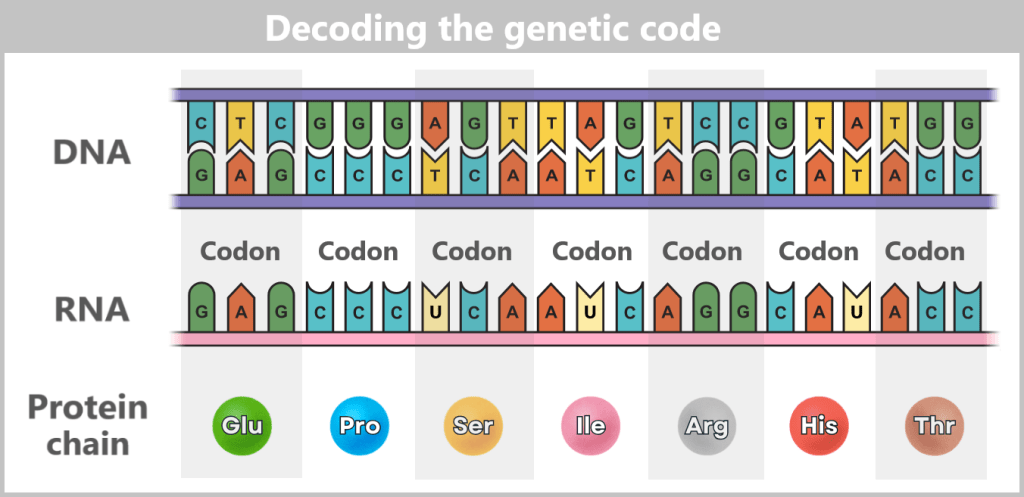

The sequence of around three billion base pairs is as unique as a fingerprint. It forms the genetic code – the instructions for producing proteins, the molecules that control the structure, function and regulation of all biological processes.

As a central information archive, DNA is both extremely valuable and sensitive. That is why it is stored safely in the cell nucleus, comparable to a safe. In order for the body to access the information in this safe, it needs a clever transport system. After all, the blueprints for proteins – the molecular architects of all life processes – must reach the ribosomes, the so-called „protein factories“ in the cytoplasm. This is where proteins are produced – a process known as protein biosynthesis.

But how does a specific blueprint travel safely from the cell nucleus to these factories? In other words: How is the genetic information for a particular protein transferred from its protected archival location to the site of production?

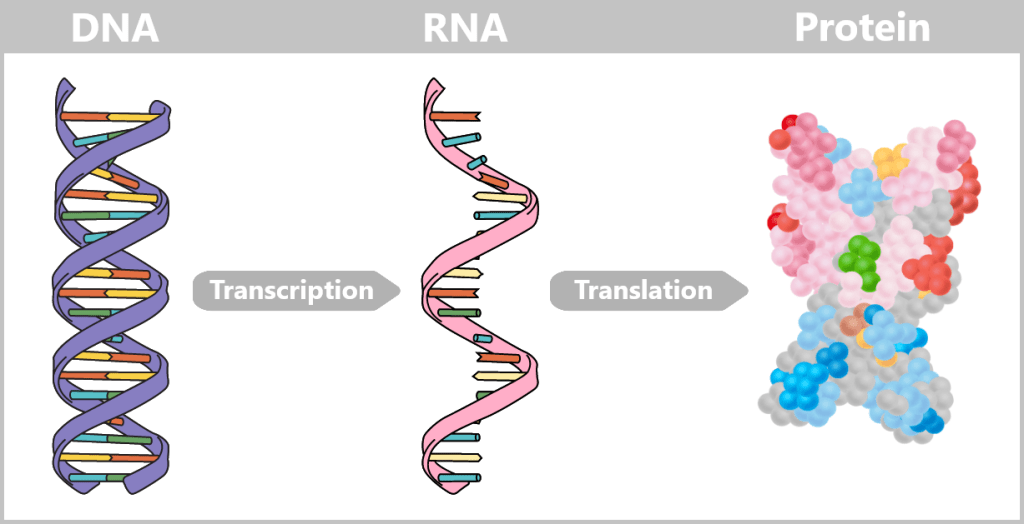

b) From Code to Protein: How Instructions Become Reality

The journey begins with the genes – specific sections of DNA that contain the blueprints for proteins. There are around 20.000 such genes in the human genome.

DNA is not just a passive information archive in the cell nucleus – it contains an active repertoire of instructions. You can think of each gene as a chapter in a molecular cookbook: often with multiple versions of a recipe, adapted to the cell type, developmental stage, or external conditions.

First, a temporary „working copy” of a gene is created – in the form of RNA (ribonucleic acid). It resembles DNA but uses the base uracil (U) instead of thymine (T) and usually consists of a single strand. This transient structure makes RNA ideal for short-term use – it is degraded after fulfilling its function.

Alternative Splicing: The Flexible Kitchen of Genes

Cells must adapt flexibly to changing demands: responding to inflammation, defending against pathogens, building muscle, or regulating blood sugar levels. This requires not a rigid set of instructions, but a system capable of improvising depending on the situation.

Depending on the cell type and external signals, the RNA strand is dynamically modified by being cut at specific markers – transferred from the DNA. Unneeded sections (introns) are removed, and the remaining sections (exons) are reassembled. This process creates a multitude of possible messages from a single template. The result is messenger RNA (mRNA), which carries the genetic information from the nucleus to the ribosomes in the cytoplasm – the cell’s „protein factories”.

You can think of this process like following a recipe: depending on the need, the cell leaves out certain ingredients, adds spices, or adjusts the preparation steps. In this way, a single basic instruction can yield a wide variety of dishes.

Through this process – called alternative splicing – cells can produce a variety of different proteins from a single gene, each performing specific functions.

The entire process „from gene to protein” is often referred to as gene expression.

💡Example: The Titin Gene

👉 Longest human gene (≈ 300,000 base pairs).

👉 Through alternative splicing, more than 20,000 different protein variants are produced – each adapted to the specific requirements of different muscle types.

Our genome is therefore not a rigid recipe book – it is a dynamic kitchen, where the cell constantly develops new solutions from the same templates.

📌 If you are interested in how genetic information in DNA is translated into protein step by step, you can find further information here.

But as in any creative kitchen, errors can also occur during the transfer from DNA to mRNA: if a „letter” in the recipe is missed, swapped, or incorrectly assembled, the message can end up misleading or unusable. Such mutations or faulty splicing are sometimes harmless – but they can also produce defective proteins that fail to perform their function or even cause harm. A small slip in copying the molecular cookbook – and the flavor of life changes.

c) Epigenetics & Non-coding DNA: The Conducting Team of Our Genome

Although all cells contain the same DNA, they only use a fraction of it. A liver cell needs different instructions than a nerve cell – the rest remain dormant. This targeted gene regulation is controlled by epigenetic mechanisms: small chemical markers – such as methyl groups – do not change the genetic sequence itself, but influence whether a gene is active, how often it is read, or whether it remains completely silenced.

But who actually gives the conductor his instructions? This is where non-coding DNA comes into play – 98% of our genome, long dismissed as useless „junk”. It is the operating system that provides the epigenetic control programs. Only through its interaction is it determined when, where, and how strongly our genes become active – and thus it helps decide over health and disease.

d) The Hidden Control Center: What Non-coding DNA Regulates

These „dark“ regions conceal precise circuits that control the fate of each cell:

Enhancers act like invisible remote controls for genes. Even across thousands of base pairs, they can activate or silence a target gene – for example, for heart development in the embryo.

Telomeres are the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, like the plastic tips on shoelaces. But when they shrink, aging begins – a central mechanism of cellular decline and cancer development.

Non-coding RNAs act as hidden directors: microRNAs block disease-causing genes, while the long RNA XIST silences an entire X chromosome in females.

Epigenetic markers lay an invisible map over the genome. With methylations acting like red stop signs, they decide whether an enhancer or gene may be read – or silenced.

This is how order emerges in the molecular cookbook: each cell type reads only the pages it needs – guided by non-coding DNA and its epigenetic interpretation.

e) When the Operating System Makes You Sick

Almost all genetic risk markers for common diseases – from diabetes and heart disease to mental disorders – are located in non-coding zones:

Mutations in an enhancer of the MYC gene can trigger leukemia by driving cell division out of control.

Epigenetic misprogramming in these regions – caused, for example, by chronic stress or environmental toxins – can permanently switch genes on or off incorrectly, thereby promoting diseases such as cancer or autoimmune disorders.

Some of these epigenetic patterns are partially reversible – a glimmer of hope for new therapies.

f) Open Mysteries in Research

Despite tremendous progress, the genome remains full of unsolved mysteries:

The „dark matter”: About half of the non-coding genome remains functionally unexplored. Is it evolutionary noise – or an as-yet uncharted regulatory network of life?

Long-range communication: How does an enhancer reliably find its target gene among millions of DNA bases? The spatial folding of the genome – a true „chromatin origami” – could be the key.

Environmental influences: Why do identical non-coding mutations lead to completely different clinical pictures in different life contexts?

RNA codes: Tens of thousands of non-coding RNAs have been discovered – but which are mere footnotes, and which might emerge as leitmotifs for new therapies?

g) The True Magic of Genes

Non-coding DNA is not junk data, but the cell’s mastermind. Epigenetics, in turn, acts as its conductor – flexibly interpreting the instructions of the operating system. Together, they shape our development, regulate our health, and respond to environmental signals.

Genes are not a rigid destiny, but more like a musical score that can be continually reinterpreted. In this interplay, an orchestra emerges that not only shapes our cells but constantly retunes itself – influenced by experiences, environmental factors, and even traces that can be passed on to future generations.

The true magic lies in the fact that from a limited set of notes, an infinite diversity of life can emerge.

4.2. Genetic Variation and Its Consequences

When the genome miswrites, falls silent, or improvises.

With every cell division, DNA is carefully copied and passed on to daughter cells – ensuring that genetic information is preserved across generations.

However, the system is not infallible: mutations – changes in the DNA sequence – can affect the structure and function of proteins. Sometimes only a single „letter” is incorrect. Sometimes a „sentence” is missing, or an entire „paragraph” has been rearranged. In genetics, these are called variants – genetic changes that can be harmless, pose a risk, or cause disease, depending on their type, size, and location.

The following overview presents the main types of variants – and what they mean in the molecular manuscript of life:

📌 SNVs (Single Nucleotide Variants) – A single „letter” is swapped. Usually barely noticeable, but sometimes enough to rewrite entire stories, as in the case of sickle cell anemia.

📌 Indels (Insertions/Deletions) – Small fragments of text are inserted or deleted. Even a tiny shift can throw entire „sentences” out of sync, sometimes so much that the original meaning is lost.

📌 Structural Variants (SVs) – Long stretches of DNA are inverted, duplicated, or relocated. These hidden „rewritings” are difficult to detect – and can often have serious consequences, as seen in cancer

📌 Splice-Site Variants – Errors at the junctions disrupt the RNA syntax. This creates incorrect blueprints, resulting in proteins that no longer function properly.

📌 Repeat Expansions – Base sequences are compulsively repeated until they distort the „text”. This causes diseases such as Huntington’s disease.

📌 Copy Number Variants (CNVs) – Entire „chapters” (genes) are missing or duplicated. The balance of the story is lost.

📌 Mitochondrial variants – Changes in the DNA of mitochondria, the cell’s power plants. If the „text” here is altered, the drive of life falters.

📌 Somatic variants – Arise only during a person’s lifetime and affect specific groups of cells. They mainly shape the story of tumors.

📌 Epigenetic signals – Not new letters, but a different emphasis: volume, rhythm, timing. They transform the same text into an entirely new melody.

The list shows that our genome is not a rigid structure but can be altered by variants. Some of these changes remain inconspicuous footnotes, while others can rewrite the entire story – sometimes with dramatic consequences.

To make such subtle differences visible, tools are needed that capture every detail – every letter, every punctuation mark, every shift. This is precisely where modern genome sequencing comes in.

4.3. Genome Sequencing: Key to Individual Genetic Material

The genetic material of a human being resembles a gigantic library: billions of letters, neatly arranged in long volumes. To read it, genome sequencing is required – which, like a high-precision scanner, provides the raw text of our genetic blueprint.

Thus, it becomes the heart of personalized medicine – a form of medicine that bases its decisions on the individual, not on the average.

But how do we even get hold of the „Book of Life“ so that we can read it page by page?

Let’s imagine the following: shortly after birth, a newborn undergoes a DNA test – a scenario that has already become reality in the United Kingdom, as described earlier.

a) The Journey of DNA: From Umbilical Cord Blood to Genetic Information

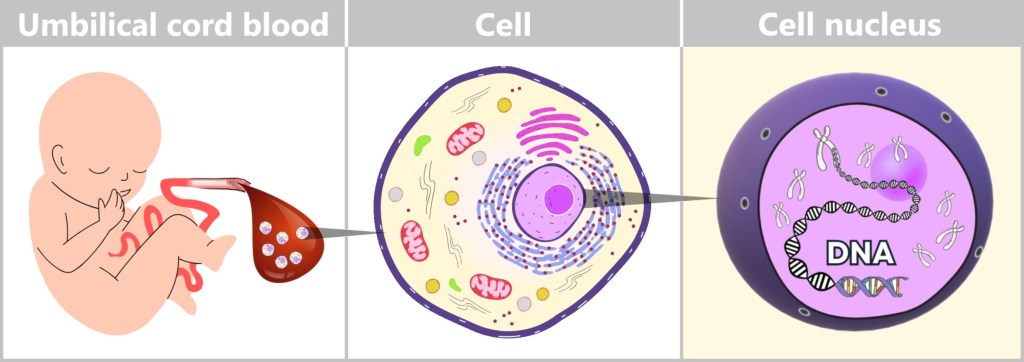

Immediately after birth, blood can be collected from the clamped umbilical cord – a safe and painless procedure. Umbilical cord blood originates from the newborn and contains numerous valuable cells, especially stem cells and white blood cells. Hidden within their nuclei lies what truly matters: the DNA – the child’s genetic inheritance.

Left: Umbilical cord blood as a rich source of diverse cell types.

Center: Schematic representation of a human cell.

Right: Inside the cell nucleus lies the DNA, the carrier of genetic information.

To isolate and analyze this DNA, it undergoes a multi-step process in the laboratory. This involves established molecular biology methods that can be divided into four key steps:

Cell Lysis: Gaining Access to the Genetic Material

First, the blood is centrifuged – spun at high speed. During this process, the components separate according to their density: the white blood cells settle as a cell pellet at the bottom. They contain the majority of the DNA of interest.

These cells are then treated with specialized solutions and enzymes that dissolve the cell and nuclear membranes. This releases the DNA – initially, however, as part of a mixture containing proteins, lipids, and other cellular components.

DNA Isolation: Obtaining Pure Genetic Material

In the next step, the DNA is extracted from the cell lysate – the „cell soup.” Several methods can be used for this purpose:

Filtration or column purification: The solution is passed through special filter systems to which the DNA adheres, while smaller molecules are washed out.

Magnetic beads: More modern methods use tiny beads with a DNA-binding surface. The DNA sticks to them and can be removed in a targeted manner using a magnet.

Both methods allow for an effective separation of genetic material from contaminants.

Purification and Concentration of the DNA

At this stage, the DNA from many white blood cells is present in a relatively pure form – but still dissolved in an aqueous solution. To further purify and concentrate it, cold alcohol (e.g., ethanol or isopropanol) is added. This causes the DNA to precipitate and become visible as a whitish, thread-like substance.

Human DNA is extremely long: if fully stretched out, it measures about two meters per cell. During extraction, however, it is broken into many smaller fragments by chemical and mechanical forces. At first, this seems chaotic – but because the DNA is identical in all cells, many fragments contain overlapping information. This random distribution becomes an advantage during sequencing: the fragments can be read multiple times independently and then assembled on a computer into a complete sequence. This significantly increases the accuracy of the analysis.

Quality Control: Is the DNA Intact?

Before the DNA sample can be analyzed, its quality must be assessed. Two common methods are:

Spectrophotometry: Measures the concentration and purity of the DNA by analyzing light absorption.

Gel electrophoresis: DNA fragments are passed through a gel and separated by length (longer fragments move more slowly than shorter ones). This allows assessment of whether the sample is sufficiently intact.

Why is this process so important?

Human DNA is fragile – contaminants or fragmentation can distort analyses or render them unusable. Careful and controlled purification is therefore essential for reliable genetic results.

Umbilical cord blood is a particularly valuable source of medical information: it enables early diagnosis, prognoses, and in some cases targeted prevention.

What appears to be a routine procedure in the lab is, in fact, a highly precise process – it requires technical expertise, modern equipment, and biochemical finesse. With automated extraction methods, it is now possible to obtain a high-quality DNA sample from just a few drops of umbilical cord blood in less than an hour. Although the DNA consists of fragments, it still contains all the information needed to decode an individual’s genetic code – and thus lays the foundation for the medicine of tomorrow.

b) Three Directives for Gene Diagnostics: WGS, WES, and Panel

Before we dive deeper into the tools of genome sequencing, it is worth taking a look at the three central strategies used today to decode genetic information – like stage directions in the script of life:

🎯 Panel Sequencing – The Targeted Scene

Only a selected part of the genome is examined here – usually a few dozen to a few hundred genes. Such tests are used when a specific disease is suspected, such as hereditary breast cancer (BRCA1/2).

Advantage: Fast, cost-effective, and precise – as long as the medical question is well-defined.

Limitation: Everything outside the selected scene remains in the dark.

🎥 Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) – The Classic Director’s Cut

WES analyses all protein-coding sections of the genome – approximately 1–2% of the entire genetic material. It is a proven method, particularly for rare hereditary diseases, as most known mutations are located in these areas.

Advantage: Efficient identification of faulty blueprints for proteins.

Limitation: Regions outside the genes – important switches and regulators of the genome – are not captured.

🎬 Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) – The Complete Movie in 4K

WGS reads the entire genome – all three billion letters. This provides the most comprehensive picture, including non-coding regions, regulatory elements, structural variants, and rare mutations.

Advantage: Maximum resolution for complex cases.

Example: In children with unclear developmental disorders, WGS provides clarity twice as often as WES – for instance, by uncovering mutations in distant „remote-control” regions (enhancers) that incorrectly switch genes on or off.

Conclusion:

Depending on the question at hand, the right perspective is needed – sometimes a zoom on the key scene suffices, other times the entire film must be re-edited. Choosing the method is therefore not a mere technical detail, but a strategic decision in the diagnostic playbook.

4.4. Methods of Genome Sequencing

How is the genetic code read?

Imagine DNA as a book – written in a language with only four letters: A, T, C, and G. To decipher this genetic text, scientists use modern technologies. Two central methods have become established. They pursue the same goal: to determine the sequence of DNA letters as precisely as possible.

The first method works – put simply – like a molecular photocopier equipped with color sensors. The second uses a high-tech tunnel through which the DNA is guided and electronically „scanned”, comparable to running your fingers along a rope to detect the smallest irregularities. These techniques form the foundation of DNA sequencing.

4.4.1. Method 1: Copying with Fluorescent Dye

a) Sanger Sequencing

b) Illumina Technology

c) Single-Molecule Real-Time(SMRT) Sequencing

4.4.2. Method 2: High-Tech Tunnel – Electrically Scanning DNA

a) Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

4.4.3. Genome Sequencing – Technologies Compared

a) Throughput vs. Usability – Quantity Does Not Always Equal Quality

b) Cost-Effectiveness – Cost per Base vs. Cost per Insight

c) From Sample to Result – How Quickly Does the Whole Genome Speak?

d) Clinical Applications – Which Technology Fits Which Purpose?

e) AI as Co-Pilot – Automation Without Relinquishing Responsibility

f) Comparison Table: Sanger, Illumina, PacBio, ONT

g) Key Takeaways: Between Maturity and Routine

4.4.1. Method 1: Copying with Fluorescent Dye

This method takes advantage of the fact that DNA consists of two complementary strands. If the base sequence of one strand is known, the sequence of the complementary strand can be automatically deduced. To obtain this information, one of the two strands of the DNA under investigation is copied. The aim is to record the exact sequence of bases in the resulting copy during this copying process.

To better understand how this process works, let’s first take a look at the key components and basic steps involved in producing a DNA copy in a test tube (in vitro).

Producing a DNA Copy – The Basic Principle

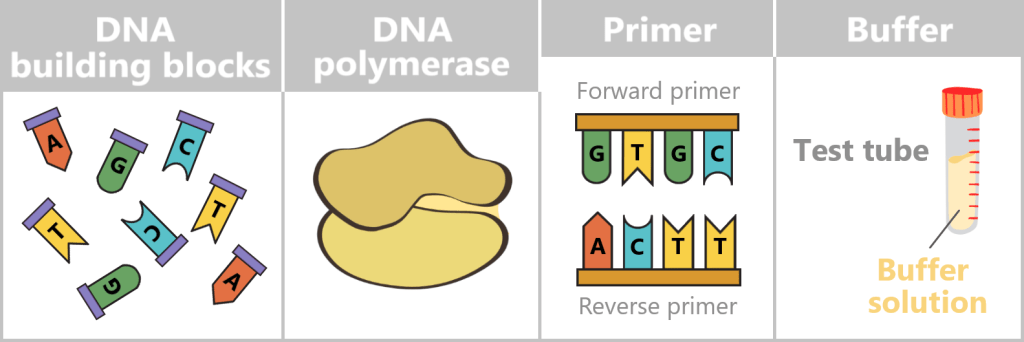

At the centre is a DNA template that is to be copied. This requires four main components:

- dNTPs (deoxynucleoside triphosphates): the DNA building blocks A, T, C, and G.

- DNA polymerase: an enzyme that functions as a molecular copying machine.

- Primers: short DNA fragments that provide the polymerase with a starting point.

- Buffer solution: ensures stable conditions during the reaction.

DNA building blocks: Individual nucleotides (A, T, C, G), shown in different colors and letters. They serve as the raw material from which the new DNA strand is assembled.

DNA polymerase: A schematic enzyme that links the nucleotides together to form a DNA strand.

Primer: Short DNA fragments that provide the polymerase with a defined starting point.

Buffer: A test tube containing buffer solution, ensuring stable chemical conditions during the reaction.

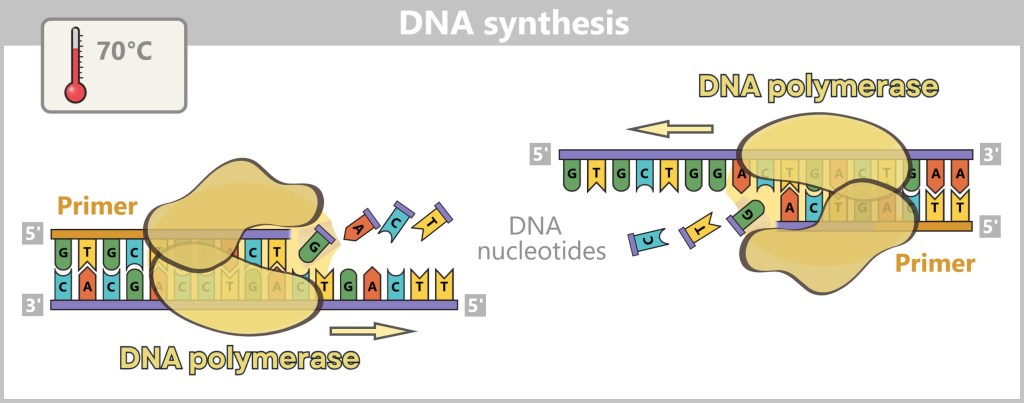

What does DNA polymerase do?

DNA polymerase is a specialized enzyme that generates complementary DNA strands – essentially the „printhead” of a molecular copying machine. Enzymes act as biological tools that enable chemical reactions in a targeted and efficient manner, which is why they are often described as „biological catalysts”.

In order for the polymerase to work, it needs a primer as a start signal. You can think of it like this: just as a printhead only starts working when a sheet of paper is inserted correctly, the polymerase only begins its work when a primer is present. This small piece of DNA shows it where to start – essentially acting as the first sheet in the molecular printer.

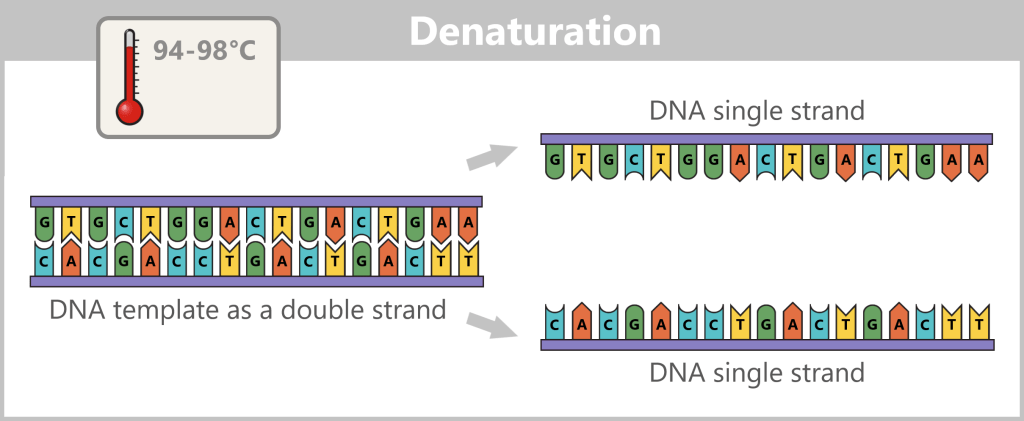

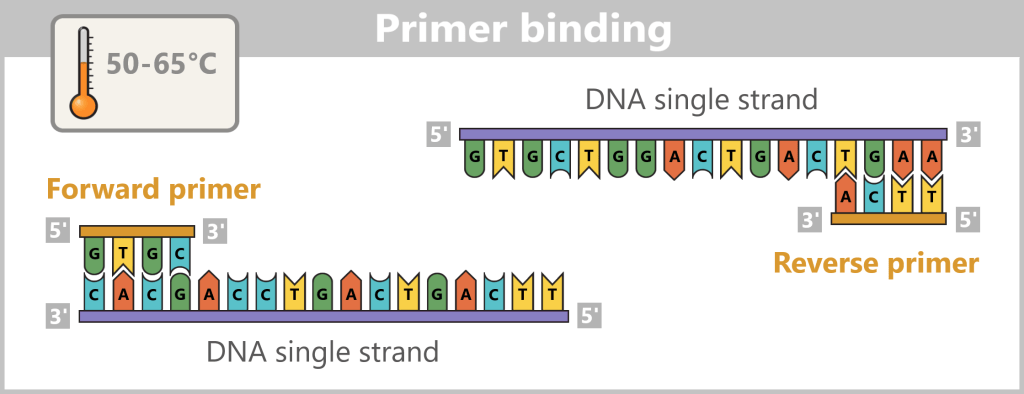

Before copying can begin, the double-stranded DNA must first be separated into two single strands – this step is called denaturation.

Next, the primers bind to their complementary target sites on the single strands. This primer binding marks the starting point for the DNA polymerase.

Now the synthesis of the new strands begins: The polymerase reads the template strand in the 3′-to-5′ direction and extends the copy in the opposite direction – 5′ to 3′ – while obeying the base-pairing rules (A with T, G with C).

What do 3′ and 5′ mean?

The designations 3′ (three-prime) and 5′ (five-prime) come from the chemistry of the DNA backbone. They indicate at which end certain carbon atoms are located in the sugar molecule, to which new building blocks can be attached.

Imagine the DNA strand as a one-way street. The polymerase can only travel in one direction – from the 5′ end to the 3′ end. New building blocks can only be chemically attached at the 3′ end. Therefore, the polymerase reads the ‘old’ strand backwards (3′ → 5′) and builds the new strand forwards (5′ → 3′).

In this way, a new, complementary strand is gradually formed from a single strand – with the help of the base pairing rules: adenine (A) pairs with thymine (T), and cytosine (C) with guanine (G).

The result is perfect genetic replicas – new DNA strands that are exact copies of the original DNA.

Fluorescent Nucleotides: How Sequencing Works

Modern sequencing methods enhance this copying process with a sophisticated technique: they use fluorescently labeled dNTPs (DNA building blocks). Each of the four nucleotides (A, T, C, G) is tagged with a dye that emits a specific light signal when it is incorporated.

As the polymerase extends the DNA strands, it inserts the colored building blocks with precision. Each time a new nucleotide is incorporated, it sends out a tiny light signal – like a small flash that reveals which „letter“ has just been added. High-resolution cameras capture these light signals, enabling the DNA sequence to be reconstructed step by step.

Overview of Sequencing Methods

Several major technologies apply this principle in specific ways:

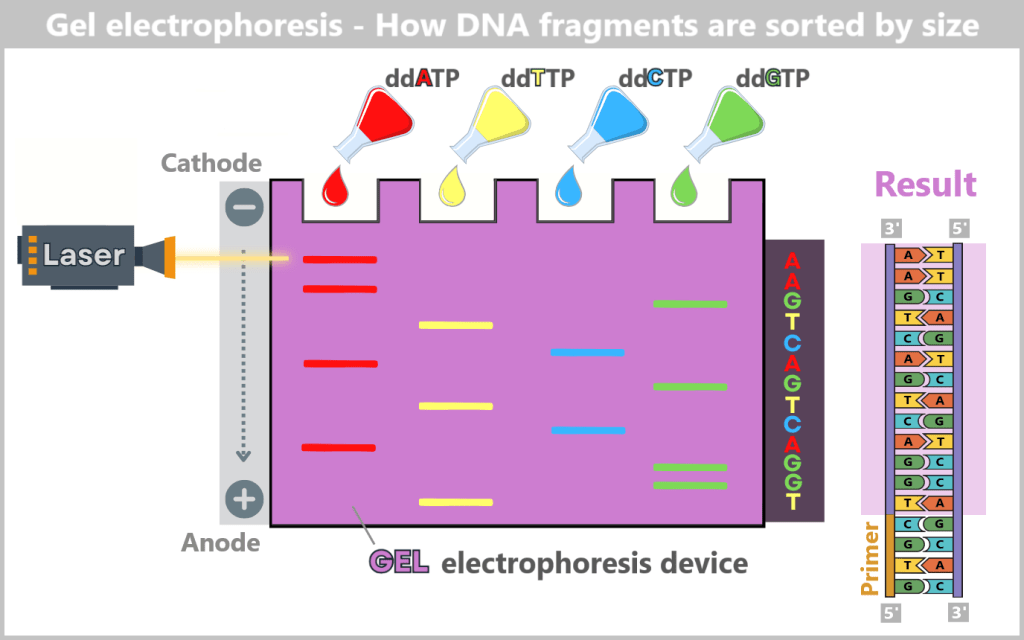

Sanger Sequencing: The classical method, in which fluorescent chain-terminating nucleotides halt DNA synthesis at random positions. The resulting fragments can be read in sequence.

Illumina Technology: A widely used high-throughput method in which millions of DNA fragments are sequenced in parallel. The fluorescent signals are recorded step by step.

SMRT Sequencing (PacBio): In this method, synthesis is observed in real time on a single DNA molecule, offering high precision and long read lengths.

a) Sanger Sequencing

The classic „letter-by-letter” reading method.

Sanger sequencing, also known as the chain-termination method, was developed in the 1970s and was the first technique to read DNA accurately and reliably. It is fundamentally based on the same principles as DNA synthesis but differs in several key aspects:

👉 Only a single primer is used.

👉 In addition to the normal DNA building blocks – the dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) – special fluorescent chain-terminating nucleotides, called ddNTPs (ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, ddTTP), are added in small amounts. When a ddNTP is incorporated, DNA synthesis stops precisely at that point. Each of the four ddNTP types carries a different fluorescent color corresponding to its base.

The process – step by step

For sequencing, four separate reaction mixtures are prepared. Each contains:

- the single-stranded target DNA,

- a primer (starting point for synthesis),

- a DNA polymerase,

- normal dNTPs,

- and one type of the fluorescently labeled ddNTPs.

Each mixture contains the same basic components but differs in the specific type of fluorescently labeled chain-terminating nucleotides (ddNTPs) added.

After primer binding, the polymerase reads the DNA strand and incorporates the complementary nucleotides to build a new strand. If a ddNTP is randomly incorporated, synthesis terminates precisely at that position.

This generates many DNA fragments of varying lengths – each ending with a fluorescently labeled nucleotide. Since each of the four reactions contains only one type of ddNTP, the terminal base of each fragment is known precisely.

Each reaction mixture contains only one type of modified DNA building block (ddATP, ddTTP, ddCTP, ddGTP). When such a „stop” nucleotide is incorporated during DNA synthesis, the copying process halts precisely at that point. In the ddATP mixture, synthesis stops upon incorporation of a modified adenine (A); in the ddTTP mixture, it ends with a modified thymine (T). Likewise, ddCTP and ddGTP terminate synthesis when a modified cytosine (C) or guanine (G) is added. This procedure generates many DNA fragments of varying lengths, each ending with a specific stop nucleotide. The goal is to produce all theoretically possible fragments so that the complete DNA sequence can be read.

Sorting and Analysis

The DNA fragments are then denatured (converted into single strands) and sorted by length using gel electrophoresis. The negatively charged fragments migrate through a gel towards the positive electrode. Smaller fragments move faster, larger ones slower, creating an orderly „ladder“ of fragments.

A laser then excites the fluorescent dyes attached to the terminal bases. The resulting light signals are captured by a detector. Each signal corresponds to a specific base at a specific position. The sequence of light signals thus directly reveals the DNA sequence – much like reading a book letter by letter.

Since the generated fragments are complementary to the original DNA, the original base sequence can be deduced precisely from them.

In the reaction mixtures, DNA fragments of varying lengths are generated, each ending with the same chain-terminating nucleotide – either adenine, thymine, guanine, or cytosine, depending on the mixture. These reaction mixtures are applied to a gel. When an electric field is applied, the negatively charged DNA fragments migrate from the cathode (−) toward the anode (+). The size of the fragments determines their migration speed: smaller fragments move faster through the gel’s fine pores and reach the anode first, while larger fragments move more slowly. By reading the fluorescent signals at the fragment ends, the exact order of the bases can be determined, allowing the DNA sequence to be reconstructed step by step.

Why is Sanger sequencing still considered the gold standard today?

Even half a century after its development, the Sanger method remains indispensable in many areas of molecular biology and medicine. The reason: reliability and precision.

Compared to modern high-throughput methods, Sanger sequencing is slower and suitable only for analyzing smaller DNA segments – not entire genomes. But that is precisely where its strength lies:

- Targeted questions, such as checking individual genes,

- Detection of specific mutations, or

- Validation of critical results previously identified using other methods

can be answered with precision, clarity, and interpretability using Sanger sequencing – often so clearly that the sequence of bases can be read directly from the sequencing plot.

In medical diagnostics – such as the analysis of inherited diseases or in quality control of genetic engineering procedures – this high level of accuracy is crucial. Even a single misread base can have life-altering consequences.

Another advantage: the method is standardized worldwide, has been reliably used for decades, and is governed by well-defined quality guidelines.

A Classic with Staying Power

In a world where new technologies constantly emerge, Sanger sequencing remains a reliable anchor – the old-timer among sequencing methods: not the fastest, but extremely robust, proven, and reliable. And sometimes that’s exactly what matters.

b) Illumina Sequencing

The High-Speed Copy Machine

Sanger sequencing is like precise hand-crafted work: each DNA strand is decoded step by step – reliable, but slow and expensive.

Imagine having to copy an entire book – or even an entire library – while being allowed to write down only one letter per minute.

This is precisely where the problem lies: modern cancer research, the decoding of rare diseases and the genetic monitoring of pandemics require the analysis of large amounts of data – i.e. many and/or very long DNA segments. This requires a method that is not only accurate, but also fast and affordable.

This is precisely where Illumina sequencing comes into play. It has elevated the principle of DNA decoding from manual work to industrial mass production and is now one of the most commonly used methods for high-throughput sequencing (Next Generation Sequencing, NGS). Instead of individual letters, entire pages are now read simultaneously – millions of times, in parallel, with high precision and cost-efficiency.

Unlike the classic Sanger method, where each DNA fragment is analyzed individually, Illumina operates with massive parallelization – meaning that many DNA fragments are amplified and sequenced simultaneously. How does this work?

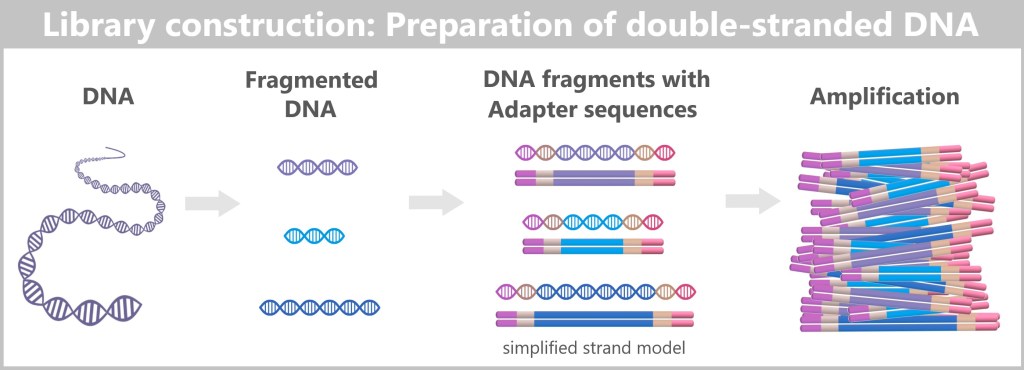

Step 1: Preparing the DNA Fragments

– Turning the DNA into a „Lego Construction Site” –

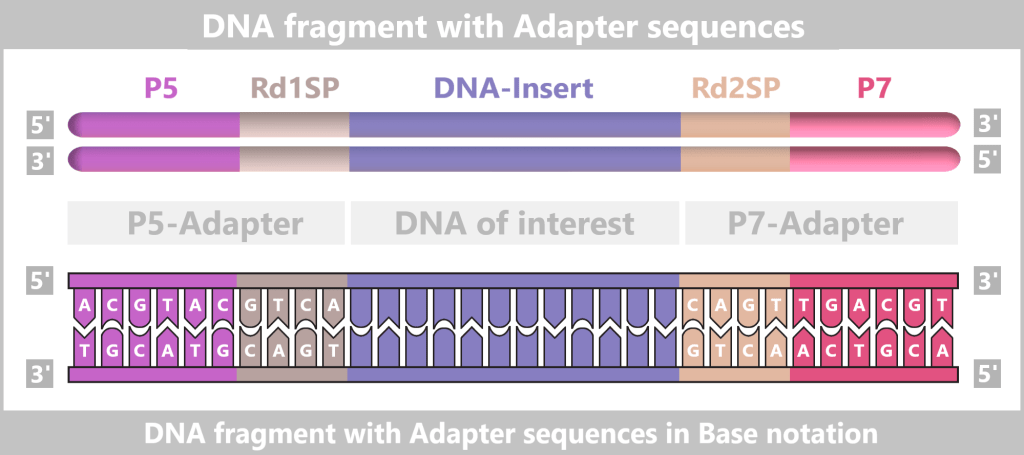

First, the DNA sample to be analyzed is broken down into many short pieces – called fragments – typically 100 to 300 base pairs long. Small synthetic DNA sequences, known as adapters, are then attached to both ends of these fragments. You can think of them as LEGO connectors. On the one hand, they act as molecular docking sites that allow the DNA fragments to bind to a special carrier – the flow cell chip. On the other hand, they serve as binding sites for universal primers.

The P5/P7 sequences serve to attach the fragments to the flow cell. The Rd1SP/Rd2SP sequences act as binding sites for universal primers.

Denaturation separates the prepared double-stranded DNA fragments into single strands.

Step 2: Bridge Amplification

– The Dance of DNA on the Flow Cell –

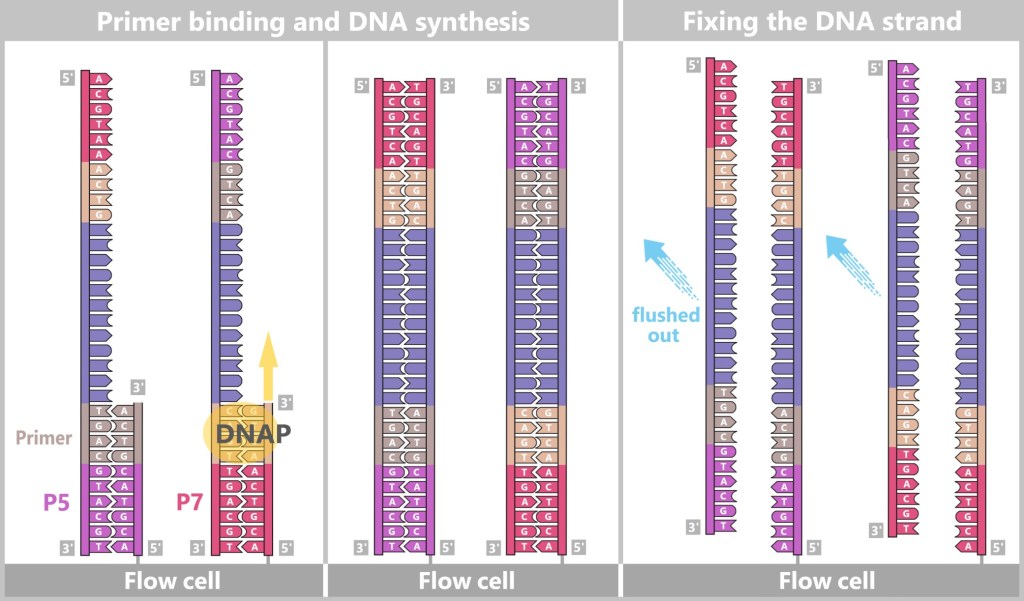

At the heart of Illumina technology is the flow cell – a glass-like plate covered with millions of tiny DNA docking sites (short DNA segments called oligonucleotides) that are firmly anchored to the surface.

The single-stranded DNA fragments bind to the anchors via their adapters. Then the molecular copying process begins: complementary copies of the DNA snippets are produced, which are now firmly anchored to the flow cell.

Left: Primers bind to the adapters (P5, P7), and DNA polymerase (DNAP) initiates the synthesis of a new complementary strand.

Center: The DNA polymerase then synthesizes the first strand.

Right: The newly formed DNA double strand is separated. After denaturation, the original strand is no longer connected to the flow cell and is flushed out. The newly synthesized strand remains firmly bound to the flow cell with its 5′ end.

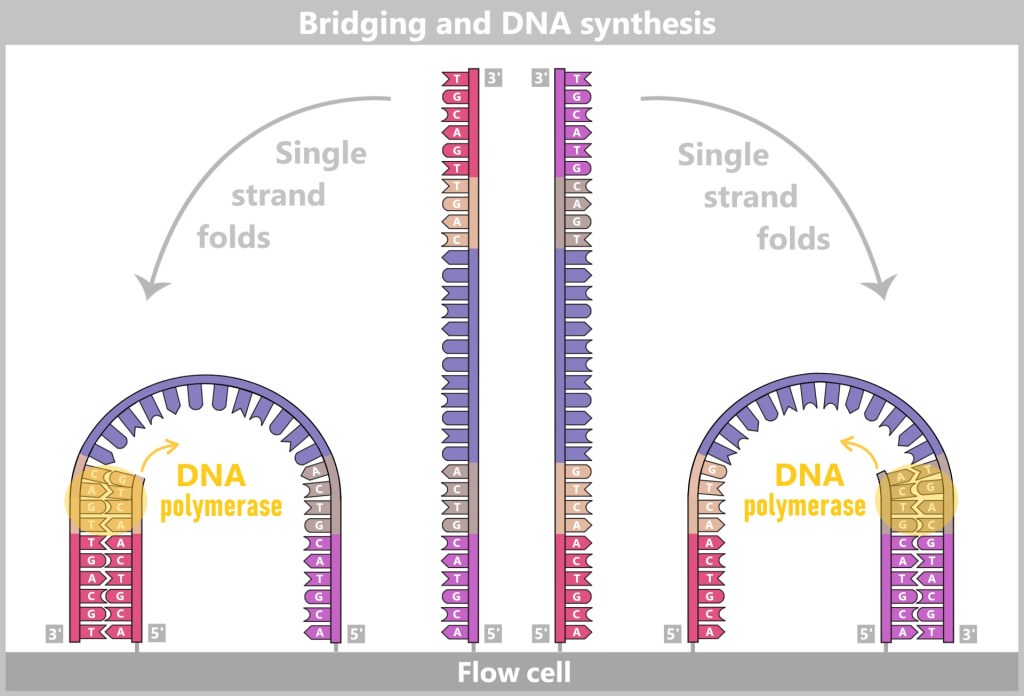

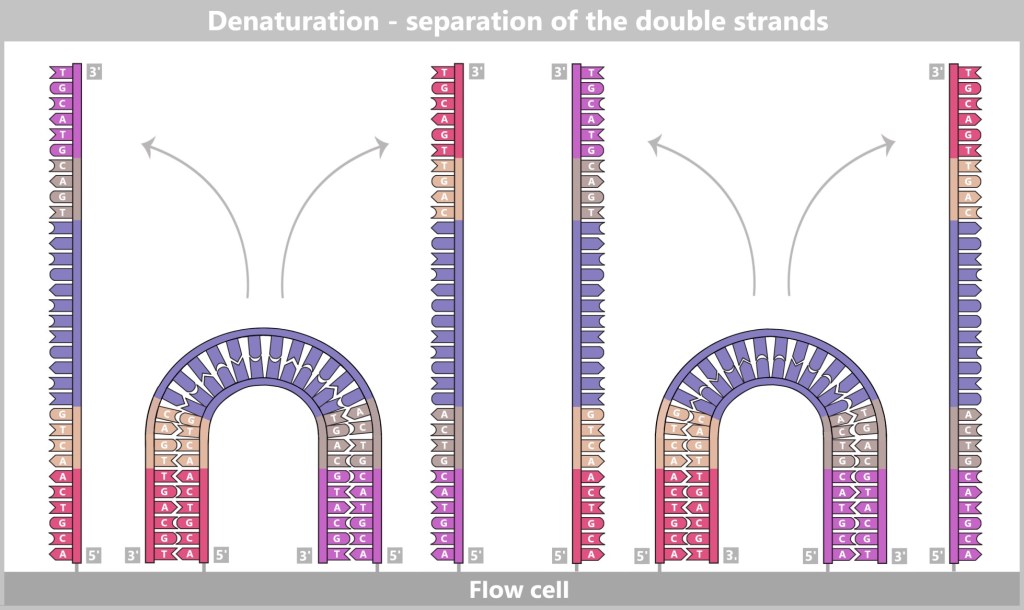

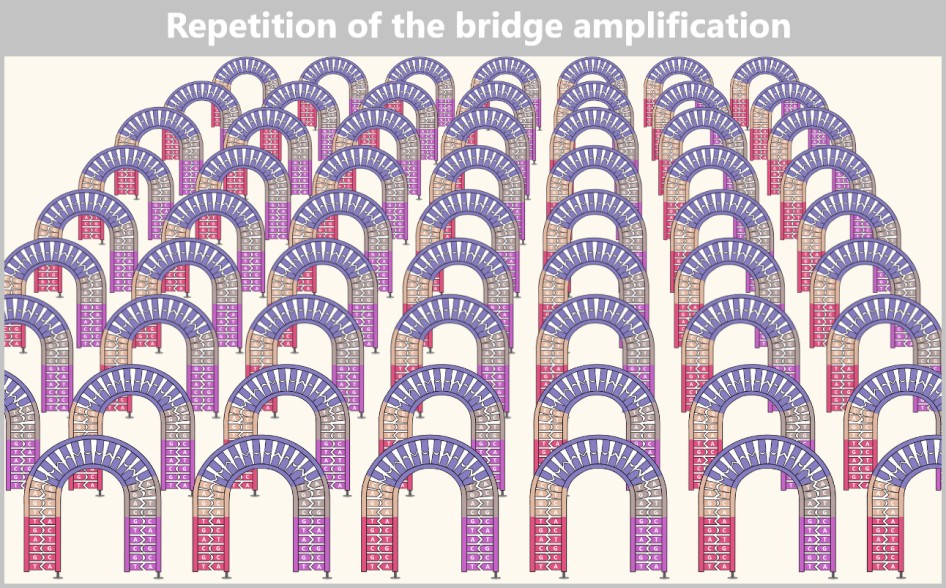

Then a fascinating process begins: the DNA strands bend to form small bridges, as their free adapters attach to neighboring oligonucleotides on the flow cell. At these points, they are copied again. After copying, the bridge is dissolved, and the number of anchored DNA strands doubles. This process, known as bridge amplification, is repeated dozens of times. In the end, dense clusters of millions of identical copies of a single DNA fragment are formed.

The anchored single strands fold and connect with neighboring anchors on the flow cell, forming a bridge structure. The copying process is then initiated.

After the copying process, the bridge double strands are separated. The number of firmly anchored DNA strands doubles, making them ready for further amplification.

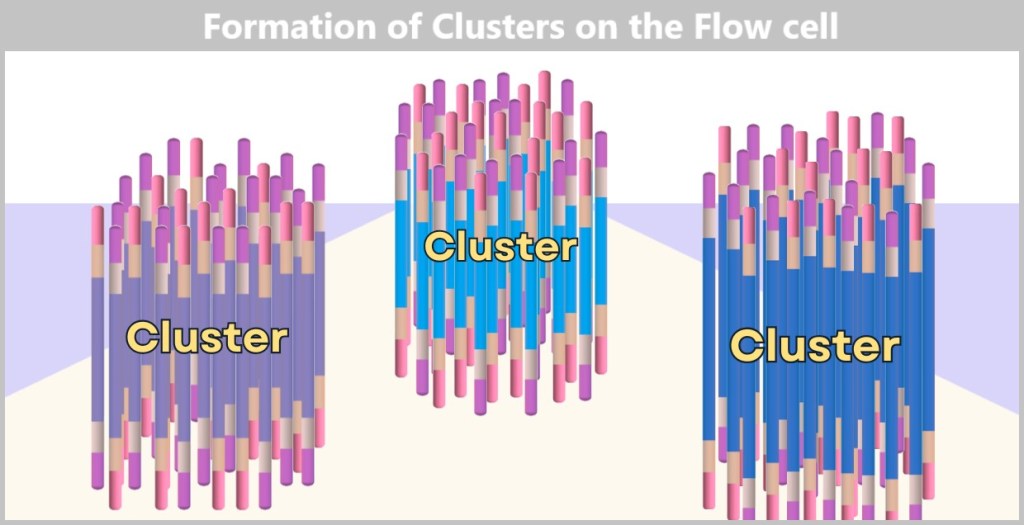

Each cluster consists of numerous copies of a single DNA fragment. In this illustration, only three clusters are shown as examples. In reality, millions of such clusters cover a flow cell, enabling high sequencing capacity.

The result is a densely packed ‘map’ consisting of millions of DNA clusters, each containing only a specific sequence – ideal for simultaneous reading.

Without this replication, reading DNA would be like trying to spot a single firefly in the wind. The clusters, on the other hand, make the DNA bases (A, T, C, G) clearly visible – like bright neon lettering in the dark.

Step 3: Sequencing-by-Synthesis

– The Light Show of DNA Bases –

Now the actual sequencing by synthesis begins. Once again, the principle of a „molecular copying machine with color sensors“ is used – but in an optimized form:

At the beginning, the universal primers bind to the corresponding adapter sites of the DNA fragments in each DNA cluster.

Then modified dNTPs – so-called RT-dNTPs (reversibly terminating nucleotides) – are added to the reaction solution. Each of the four DNA building blocks (A, T, G, C) is labelled with its own fluorescent color and carries a reversible blocker.

Only one nucleotide per cycle can be incorporated because the block temporarily stops further strand formation. Unincorporated RT-dNTPs are washed away.

After each incorporation step, the flow cell is scanned with a high-resolution camera. Each fluorescent signal corresponds to an incorporated nucleotide, and its color indicates which base has just been added.

Afterwards, the blockage and dye marking are chemically removed, and the next cycle begins.

This process is repeated cycle by cycle until each DNA strand is completely read.

Step 4: Data Analysis

– The Supercomputer as Puzzle Master –

After the „light show„, millions of photos are available – one for each cycle and each cluster. Each image shows which color (and thus which letter: A, T, C, or G) was added to each cluster.

Now powerful computers come into play – equipped with software that works as precisely as a detective piecing together a cut-up book from a stack of numbered Polaroids. Each cluster on the sequencing chip is like a small crime scene, each color pixel a clue. And from millions of such clues, a story gradually emerges – the story of DNA.

The color patterns are translated into sequences of letters, known as „reads”: tiny pieces of text from an enormous genome novel. In the end, a flood of such fragments piles up – like a mountain of cut-up book pages, scattered loosely about.

This is precisely where the real art begins: bioinformatics takes the stage. Using specialized algorithms, the snippets are analyzed, sorted, and stitched together – constantly searching for overlapping regions, familiar patterns, and known structures.

Piece by piece, the bigger picture comes back together – until, in the end, the original DNA sequence becomes visible, like a reconstructed book that suddenly makes sense.

The real „magic” therefore doesn’t happen in the flow cell, but in the computer! Without the software, the images would be nothing more than colorful flickering – but with it, they become the key to medical breakthroughs.

A more detailed yet clear explanation of the Illumina sequencing technology method can be found in the video „Illumina Sequencing Technology“.

Modern high-throughput sequencing platforms such as those from Illumina can generate the raw data of a complete human genome within just a few days – at pure sequencing costs that are significantly lower than the price of a premium smartphone.

This technology has revolutionized genome research and made it considerably more accessible: today, it is an extremely versatile tool – fast enough for real-time analysis of pandemics, precise enough to form the basis for personalized cancer therapies when combined with robust bioinformatics and clinical expertise.

Illumina sequencing is now considered the industry standard for large sequencing projects – such as the analysis of whole genomes, gene expression research, and modern cancer diagnostics.

And best of all: While you are reading this text, somewhere in the world a Flow Cell is decoding millions of DNA fragments.

However, Illumina technology also has its limitations. It reaches its limits particularly with long, repetitive DNA segments, such as those found in some chromosome regions. It is like trying to reconstruct a song from thousands of 3-second snippets. For such challenges, Illumina is often combined with other sequencing methods that can reliably capture long segments – like an investigator who needs both close-ups and panoramic images to understand the entire crime scene.

c) Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing

The Novel in One Go

Imagine you want to read a long novel – full of recurring chapters and hidden clues that span many pages. If you cut the book into thousands of small snippets, as in Illumina sequencing, read them individually and then put them together like a jigsaw puzzle, there is a risk that chapters will be missing, mixed up or incomplete. The secret messages of the story – what the novel actually wants to tell us – could be lost or appear only fragmentarily.

This is where PacBio’s Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing shines: it reads entire chapters in one go – no snippets, no breaks.

Instead of breaking the DNA apart, PacBio keeps it in very long fragments – often tens of thousands of base pairs at a time, sequenced as a whole. These strands enter tiny stages in a SMRT cell, called nanowells (Zero-Mode Waveguides). They are so small that they can hold only a single DNA molecule and a polymerase. Each of these stages allows light to act on just one tiny spot – exactly where the polymerase reads the DNA. Like a spotlight highlighting an actor during a monologue on stage.

The polymerase plays the leading role: it adds building block by building block (A, T, C, or G) to the DNA copy. Each of these blocks lights up in a different color, like neon lights at a DJ set. With every addition, a flash of light is emitted and recorded in real time by a camera – a dancing light code that reveals the DNA sequence.

The video Introduction to SMRT Sequencing by PacBio illustrates this process impressively.

Let’s analyze the individual steps of this fascinating process in detail.

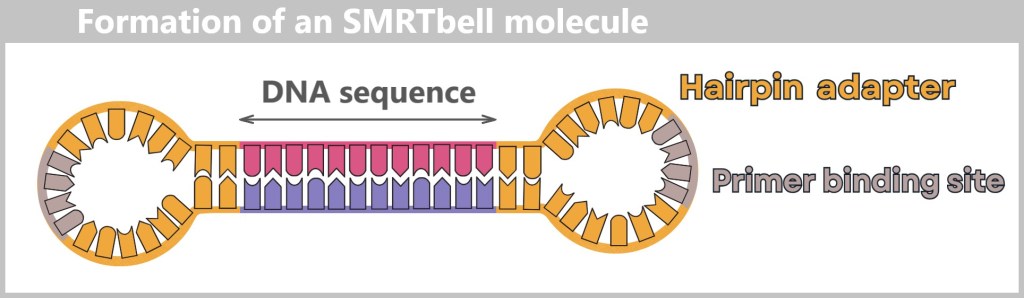

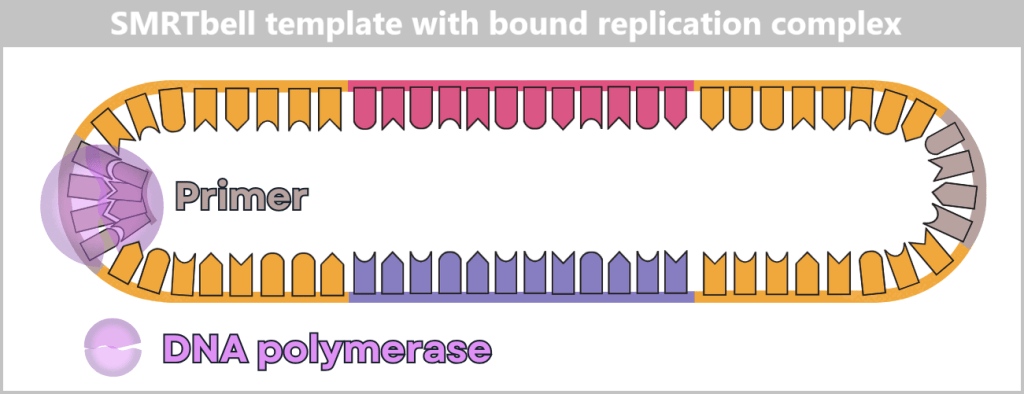

Step 1: Preparation

– DNA Loops for Continuous Reading –

Even with PacBio, the DNA to be analyzed is first fragmented – but into much larger pieces than with Illumina, usually 10,000 to over 20,000 base pairs long. These fragments are then converted into circular DNA molecules:

So-called Hairpin adapters are added to both ends – small loops of DNA that close the fragment onto itself.

The adapters contain a primer binding site, which later provides the starting point for the polymerase.

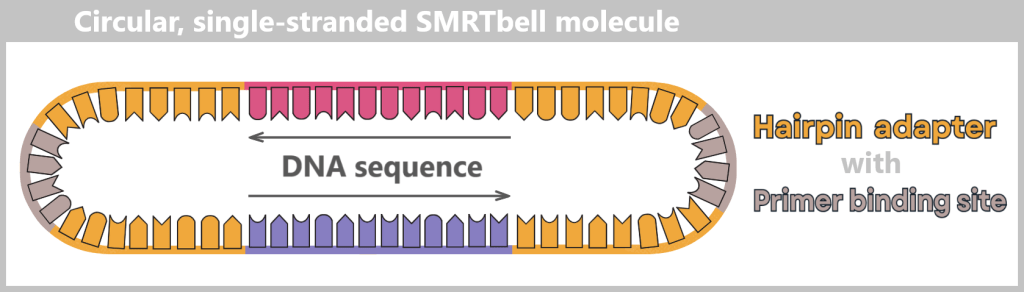

Subsequent denaturation produces a circular, single-stranded SMRTbell molecule in the form of an open loop.

Denaturation converts the double-stranded template into a single-stranded SMRTbell molecule. It forms a circular structure, shown here as an open loop.

The result is a SMRTbell: a closed DNA loop that can be read repeatedly by the polymerase – like a model train running around a circular track.

Each hairpin adapter contains a defined binding site to which the universal primer binds. This is the starting point for the polymerase.

The DNA polymerase binds to the primer complex, forming a fully functional replication complex: polymerase + primer + SMRTbell.

The primer is bound to the adapter binding site, the polymerase to the primer. This complex is ready to start DNA synthesis.

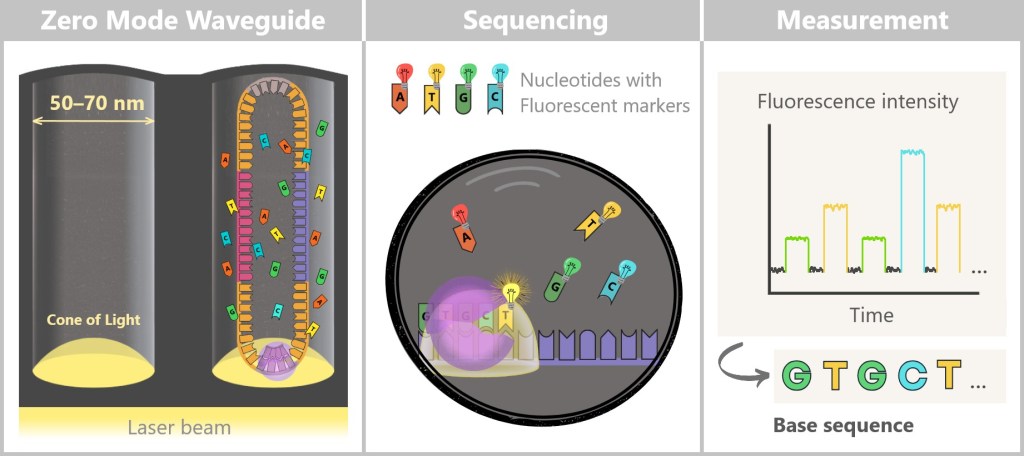

Step 2: The Sequencing Stage

– Light Shows at the Nanoscale –

Now it gets spectacular: the prepared replication complexes are guided into their tiny observation chambers – the Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs). These nanowells are so small that typically only a single SMRTbell template fits inside. The polymerase is anchored firmly at the bottom of the ZMW, ready for action.

The start signal comes with the addition of the four nucleotides (A, C, G, T), each labeled with its own fluorescent dye.

The polymerase now begins its work – it reads the DNA strand and synthesizes a complementary strand. The crucial event occurs the moment it incorporates a nucleotide:

Each nucleotide emits a brief, color-coded flash of light.

Left: At the bottom of the Zero-Mode Waveguide (ZMW), a laser beam enters and generates what is known as an evanescent field (shown as a cone of light). Unlike normal light, this field does not propagate throughout the solution but decays exponentially within only 20–30 nanometers. This creates an extremely small excitation volume in which the fluorescent dyes of the nucleotides can be excited.

The left zero mode waveguide (ZMW) contains a single replication complex (polymerase + SMRTbell). The polymerase (purple) is firmly anchored to the (glass) bottom. In the presence of the fluorescently labelled nucleotides, the polymerase begins its work.

Centre: The four nucleotides (A, T, G, C) carry different fluorescent markers. As soon as the polymerase incorporates a nucleotide, it lights up briefly before the dye is cleaved off.

Right: These flashes of light are measured in real time and translated into fluorescence signals. This is how the base sequence of the DNA is determined step by step.

The luminescence occurs in real time, at the exact moment of insertion – hence the name: Single Molecule Real-Time Sequencing. A sensitive detector records these light signals – like a molecular live microscope at work.

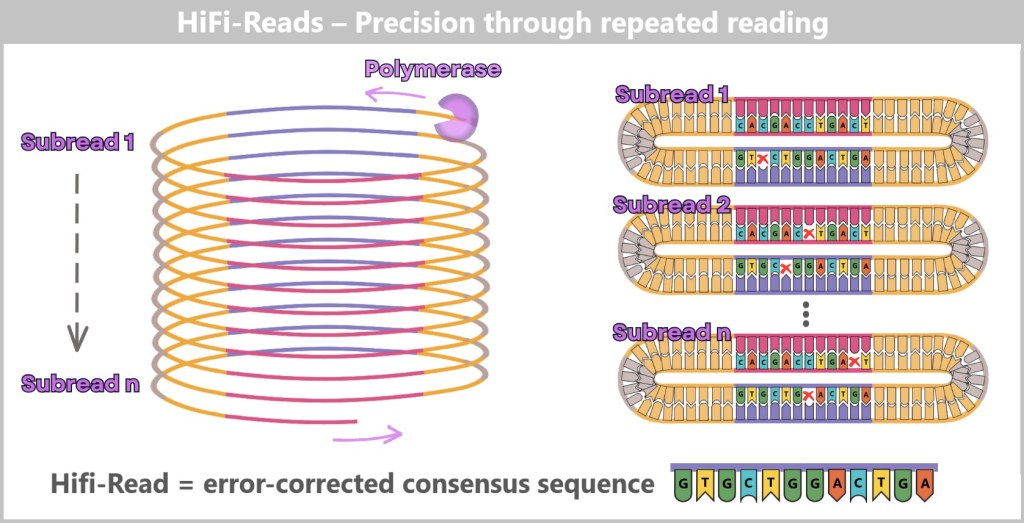

Step 3: The Long-Range Secret

– Repetition Makes It Robust –

Since PacBio reads very long DNA segments at once – comparable to reading entire chapters of a book instead of individual verses – more individual errors occur in a single run than with Illumina. This is exactly where the ring-shaped SMRTbell structure comes into play. The DNA polymerase can circle the ring molecule multiple times, like a train conductor. In doing so, the same DNA fragment is read over and over again – like a reader revisiting the same passage until it is fully mastered.

A computer compares the repeated reads with one another and filters out the errors – like an editor polishing a manuscript. This results in a particularly precise consensus sequence.

PacBio calls this approach HiFi reads – high-precision single-molecule readings.

The polymerase circles the SMRTbell template multiple times, generating multiple subreads. Each cycle corresponds to a complete reading of the DNA sequence. Individual subreads may contain random errors (x), but by comparing many repetitions, a highly accurate consensus is formed – the so-called HiFi read (High-Fidelity Read).

Additional info: How the polymerase loops around the DNA multiple times

First sequencing run

The polymerase reads the single-stranded template strand and synthesizes a complementary strand.

The result is a complete double helix – the original template strand and the newly created daughter strand are now firmly bound together.

This first, uninterrupted round produces a subread – a single base sequence generated by the polymerase in a single pass.

Second and subsequent sequencing runs

Now the question arises: how can the polymerase continue reading when the DNA ring is already double-stranded?

This is where Φ29 phage DNA polymerase comes into play – a specially modified enzyme variant with two key properties:

High processivity: It remains bound to the DNA strand for a very long time and hardly ever detaches – this enables long reads.

Strong strand-displacement activity: It can break the hydrogen bonds between the template and daughter strands.

The polymerase runs into the double helix, separates the strands locally and displaces the old daughter strand while simultaneously synthesizing a new one – like a molecular bulldozer.

The previously synthesized strand is not degraded; it remains as a loose, single-stranded DNA fragment in the nanowell. With each subsequent round, this process repeats: the polymerase reads the same template again – producing multiple subreads from the same DNA molecule.

Step 4: Data Analysis

– Turning Flashes of Light into Readable DNA –

Once all the light signals have been captured, the real detective work begins: data analysis.

The first step is called base calling: the recorded fluorescence signals – encoded in time and color – are translated into nucleotide sequences – A, T, G, or C.

Next, the raw data from each polymerase pass is cleaned up: the hairpin adapter sequences are bioinformatically trimmed. What remains are the subreads – the uncut reading records of each individual polymerase pass through the DNA chapter text.

But it is only the next step that reveals the whole truth: like a master philological detective comparing multiple copies of a manuscript, the algorithm combines all subreads of the same SMRTbell molecule. This comparison – known as Circular Consensus sequencing (CCS) – produces a highly accurate HiFi read: an error-corrected master copy that reproduces the DNA chapter word for word.

Only now is the text fragment ready for final classification – and in the process it goes through several stages:

First, a quality check – just like a meticulous editor reviewing the text for clarity and consistency.

This is followed by alignment: the sequence is classified like a new chapter in the correct compartment of a reference genome shelf.

Finally, assembly takes place – the final act, in which all chapters are brought together to form a complete novel of the genome.

The video PacBio Sequencing – How it Works clearly summarizes the steps involved.

Applications and Advantages – The Strengths of Long-Read Sequencing

PacBio SMRT technology has a particular strength: it can read very long DNA segments in one go – with highest accuracy. This makes it ideal for:

- Detecting complex genomic structures

- Analysis of repetitive sequences

- Distinguishing very similar gene variants (e.g., in immune receptors or cancer genetics)

- De novo sequencing – reading entirely new genomes without a reference

- Detecting epigenetic modifications (e.g. methylations)

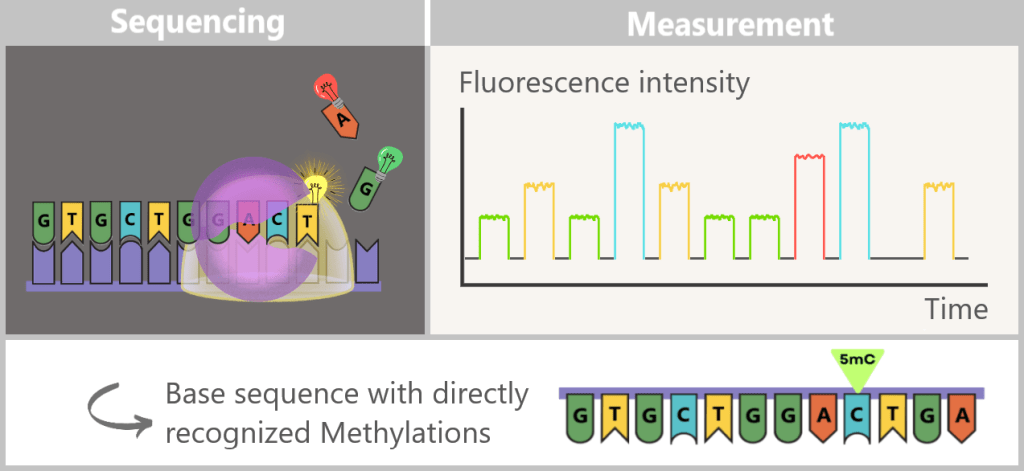

How can SMRT sequencing make epigenetic modifications visible?

As already described, epigenetic mechanisms play a central role in targeted gene regulation. These are small chemical markers – such as methyl groups – that are attached to specific DNA bases. They do not change the genetic sequence itself, but influence when and how often genes are read – depending on cell type, environment or stage of development.

They function like notes or markings in the margin of a book: the text remains the same, but the „reading” changes – some passages are emphasized, others skipped over.

If this finely tuned system falls out of balance, it can have far-reaching consequences – such as in cancer, autoimmune diseases, or mental disorders.

Unlike Illumina technology, which reads a chemically modified copy of the DNA, SMRT analyses the original DNA in real time. It measures not only the base sequence, but also the dwell time of the DNA polymerase at each base – known as incorporation kinetics.

This is precisely where the key to detecting epigenetic modifications lies: methylation and other chemical changes influence these kinetics. They act like small obstacles or skid marks on the DNA strand. The polymerase „lingers“ longer at such sites – and it is exactly this delay that is directly captured by the SMRT camera.

SMRT is particularly well suited for the direct detection of certain chemical markers, such as methyl groups on adenine or cytosine bases, which play an important role especially in bacteria and plants. For cytosine methylation (5mC), which is central in human epigenetics, direct detection is less sensitive but can be reliably derived using specialized bioinformatics tools such as pb-CpG-tools.

How SMRT Sequencing Reveals Epigenetic Modifications

During SMRT sequencing, the fluorescence signals of the incorporated nucleotides are measured in real time. At the same time, modifications such as 5-methylcytosine (5mC) can be detected, as they slightly alter the kinetics of the polymerase.

The key advantage: the extremely long read lengths reveal how methylation patterns are intertwined across large genomic regions with other factors, such as:

- gene variants,

- haplotypes (groups of co-inherited gene variants),

- repetitive sequences.

In this way, PacBio provides not only the genetic sequence of letters but also a „map” of epigenetic regulation – revealing which „pages” functionally belong together and how this network influences disease processes such as cancer or neurological disorders.

Defective Scissors in the Genome: How PacBio Unmasks Splice-Site Variants

In the section Alternative Splicing: The Flexible Kitchen of Genes, we described in simplified terms how our DNA, as a molecular cookbook, produces recipes in the form of mRNA transcripts. These transport the genetic information from the cell nucleus to the ribosomes in the cytoplasm – the cell’s „protein factories”.

The recipe is subsequently adjusted: molecular scissors remove certain ingredients (introns) and recombine other building blocks (exons). This process is controlled by splice sites – markers that are „copied“ from the DNA. These can be thought of as cutting instructions: they determine which parts of the recipe are used and how they are assembled.

But what happens if these cutting instructions are faulty? The consequences can be severe:

- Exons are skipped → parts of the blueprint are missing.

- Introns are erroneously retained → „junk” is incorporated into the protein.

- Incorrect splice sites are created → the mRNA text becomes distorted.

Such splice-site variants often lead to defective or non-functional proteins – with possible consequences such as cancer, genetic disorders (e.g. β-thalassemia), or neurological diseases. Since protein biosynthesis depends directly on the mRNA sequence, detecting such errors is crucial.

The key lies in PacBio’s ability to analyze complete mRNA molecules in one piece – usually 500 to 5,000 nucleotides long, sometimes significantly longer. Since PacBio reads DNA, the mRNA is first converted into a stable copy (cDNA, complementary DNA). This can then be sequenced in its entirety. This allows us to see exactly how the recipe is structured and which ingredients are required in which order – no transcription or splicing errors remain hidden.

In addition, the underlying DNA segment can also be sequenced. Bioinformatic tools compare cDNA and DNA sequences with reference data, revealing deviations in the splicing pattern and their genetic cause.

The DNA shows: Here the instruction is faulty.

The cDNA shows: Here the recipe is mutilated.

Only the combination of both pieces of information creates a sound basis for precise diagnoses and targeted therapeutic approaches.

Conclusion – When you want to tell the whole story

When it comes to telling the entire story of a DNA segment in one go – without cutting it into pieces or piecing it back together – SMRT sequencing is the method of choice.

PacBio-SMRT is the archaeologist of genomics: it sees the whole picture where others only provide fragments. In 2022, it played a key role in closing the last gaps in the human genome.

PacBio SMRT technology is not a mass-market product but a precision instrument. It is slower and more expensive per base pair than Illumina – but in return, it provides greater detail and versatility.

In practice, both technologies are often combined: Illumina for breadth, PacBio for depth. Together, they provide a complete picture – like a satellite image and a close-up merged into a single panorama.

4.4.2. Method 2: High-Tech Tunnel –Electrically Scanning DNA

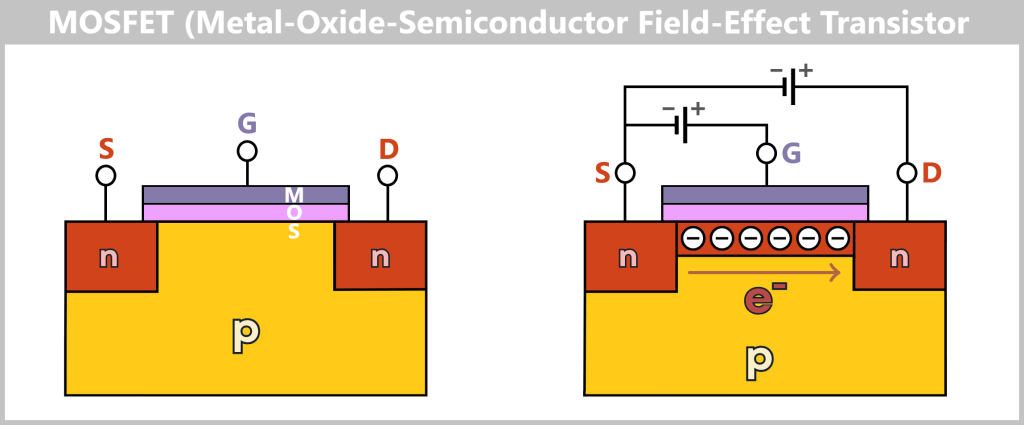

While in the molecular copying machine with color sensors the DNA is first replicated and then „photographed“ in an image, the second method works in a radically different way: the DNA is passed through a high-tech tunnel and scanned electronically in real time.

This is the principle behind Oxford Nanopore sequencing.

a) Oxford Nanopore Sequencing

DNA Through the Eye of a Needle

Imagine reading a rope by letting it slowly slide through your fingers – sensing every subtle irregularity: thickness, dents, knots. That’s exactly how Oxford Nanopore Sequencing (ONT) works: it „feels” the DNA as it passes through a tiny biological eyelet.

This eyelet – a so-called nanopore channel – is embedded in a membrane through which an electrical current flows. As soon as a single DNA molecule is threaded through this high-tech tunnel, the bases (A, T, G, or C) influence the current flow with different intensities – like pebbles of different shapes in a stream. These changes generate characteristic electrical signals that are recorded in real time.

ONT does not read light signals, but rather current patterns – an electrical „finger reading” of DNA.

A single thread – read directly

Before sequencing begins, the DNA is coupled to a motor protein that pulls it precisely through the pore – not too fast, not too slow. Unlike Illumina or PacBio, there is no need for polymerase, fluorescence, or amplification: the original DNA is read directly – a major advantage for sensitive or damaged samples.

The sequencing cell consists of two chambers: the cis chamber (top) and the trans chamber (bottom), separated by a membrane with embedded nanopores. On the left, a DNA molecule has docked onto a nanopore with the help of a motor protein. On the right, an empty nanopore is shown, through which a constant ionic current flows. The applied voltage between the negative electrode (cis) and the positive electrode (trans) drives the ion flow. The ionic current is measured in the well (a small channel in the chip), as shown in the current/time diagram. As long as no DNA passes through the pore, the current remains constant.