They are tiny, invisible, and everywhere: viruses. Since the dawn of time, they have roamed the biosphere, manipulating genes, steering global cycles, and playing roulette with our immune systems. Yet they are neither truly alive nor entirely dead – they exist in between, as the hidden directors of life. Sometimes invisible guardians, sometimes treacherous invaders. And most of the time: completely unnoticed.

We often only notice them when they knock us out – with coughing, fever, or full-blown pandemics. Then, they suddenly become enemies, fearmongers, headlines. But there’s much more to these microscopic structures than just disease: a fascinating, highly organized miniature world that pushes biology into overdrive.

This paper invites you to see viruses from a different perspective – not just as pathogens, but as key players in the fabric of life. What makes them so successful? How do they reproduce with nothing more than a few genes? How do they influence ecosystems? And most importantly: do viruses even truly exist?

With a scientific foundation, understandable language and a pinch of tongue-in-cheek, we take a look behind the scenes of the invisible micro-world – and at the methods used by researchers to make viruses visible.

Curtain up for the invisible…

📑Inhaltsverzeichnis

1. Glimpse into the Invisible World

1.1. Guardians of Nature: Viruses as Regulators of Balance

1.2. Viruses as Drivers of Evolution

1.3. Do Viruses Really Exist?

2. Viral Mechanisms Illustrated by Influenza

2.1. How the Influenza Virus Travels

2.2. The Architecture of the Influenza Virus

2.3. The Infection Process of the Influenza Virus

2.4. The Adaptability of the Influenza Virus

2.5. Entry and Exit Routes of the Influenza Virus

2.6. Mostly Localized Mucosal Infection

2.7. Viral Strategy: Efficient Replication Without Rapid Cell Destruction

2.8. Destruction of the Host Cell

2.9. Self-Limiting Dangerous Viruses: Why They Rarely Cause Pandemics

2.10. Why Does the Virus Make Some People Sick and Others Not?

3. A Look at the Beginnings of Microbiology – How It All Started

3.1. Early Discoveries: The First Glimpses into the Invisible

3.2. The Birth of Modern Microbiology

3.3. The Step into the World of Viruses

3.4. Viruses and Koch’s Postulates

4. Modern Methods for the Discovery and Analysis of Viruses

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. Sample Preparation

4.2. a) Filtration

4.2. b) Centrifugation

4.2. c) Precipitation

4.2. d) Chromatography

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Making Viruses Visible

4.4. a) Electron Microscopy

4.4. b) Crystallization

4.4. c) Cryo-Electron Microscopy

4.4. d) Cryo-Electron Tomography

4.4. e) Summary

4.5. The Genetic Fingerprint of Viruses

4.5.1. Nucleic Acid Extraction

4.5.2. Nucleic Acid Amplification

4.5.3. Sequencing

4.5.3. a) First Generation: Sanger Sequencing

4.5.3. b) Second Generation: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

4.5.3. c) Third Generation: New Approaches in DNA Sequencing

4.5.3. d) Emerging Technologies: The Future of Sequencing

4.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

5. Do Viruses Really Exist?

6. Where Do Viruses Come From?

6.1. The Tree of Life

6.2. The Main Hypotheses on the Origin of Viruses

6.2.1. Hypotheses in a Cellular World

6.2.2. Hypotheses in the Pre-Cellular RNA World

7. Why Do Viruses Exist?

Epilogue: The Inconspicuous Ones

1. Glimpse into the Invisible World

Our visible world is only half the story – around us, on us, and within us exists an invisible universe full of microscopic players. Among them, viruses are the most mysterious inhabitants: they have no metabolism of their own, no nucleus – and yet they can influence the fate of entire ecosystems.

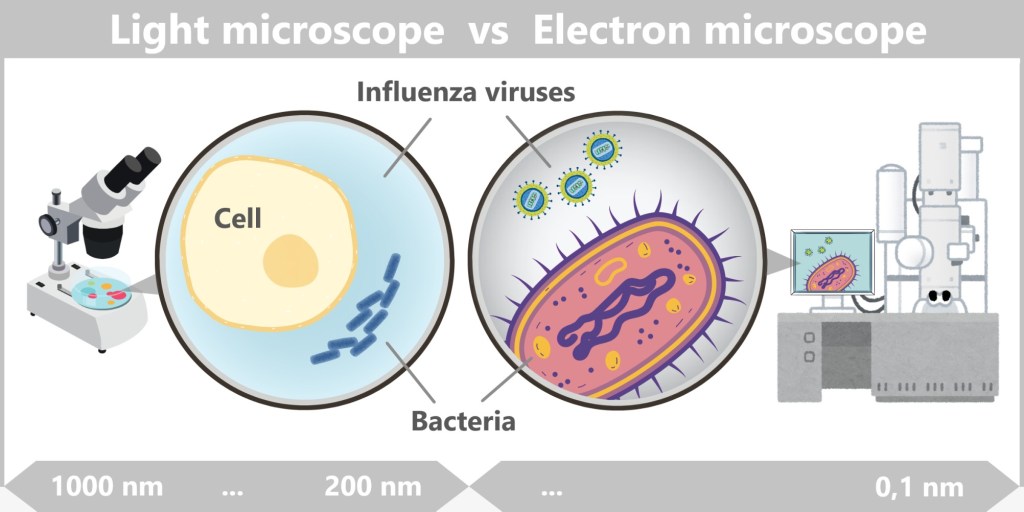

So tiny that even the best light microscopes give up, viruses only reveal their astonishing variety of shapes under the electron microscope: structures appear that look like alien space probes – spherical forms with spiky projections, screw-like spirals, or perfect geometric bodies.

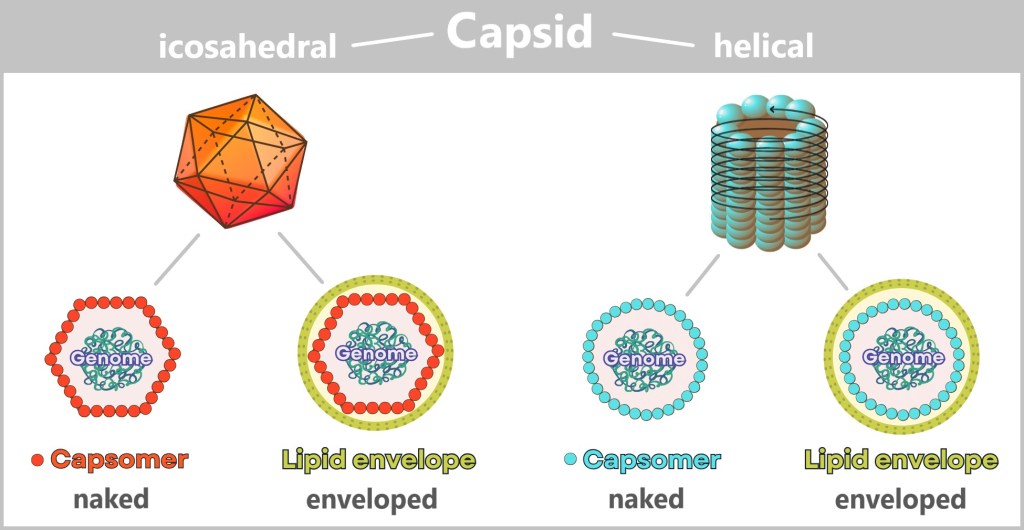

Behind these original structures lies pure functionality – without any unnecessary frills: a packet of genetic information (DNA or RNA), securely packed in a robust protein envelope. Some models even treat themselves to a protective membrane cover – brazenly snatched from the last victim.

Simple yet effective: the recipe for viral success.

Let’s first zoom into this microworld to get a sense of the scale.

The mission of a virus: infect, reproduce, survive

Every virus has a clear mission: it must find a suitable host to reproduce and survive as a species. These hosts can be humans, animals, plants, or bacteria. There are even viruses that infect other viruses. Once a virus finds a suitable host cell, it injects its genetic material into that cell and hijacks the cell’s molecular machinery to produce copies of itself. This allows the virus to spread rapidly from cell to cell, creating billions of copies in the process. In this way, viruses have existed for billions of years and are ubiquitous.

The Life Cycle of a Virus: Dormant Phase vs. Attack Mode

A virus exists in two radically different states – almost like a double agent:

— The Extracellular Phase: The Virion —

Existence as a „nanospore“: an inactive but infectious particle.

Task: surviving outside host cells – on doorknobs, in droplets, in soil.

Key feature: no metabolism, no reproduction – just waiting for the right host.

Like a seed carried by the wind: inert, yet full of potential life.

— The Intracellular Phase: The Active Virus —

Brutal efficiency: A single virion can produce over 10,000 new viruses.

Mission Start: As soon as a suitable host cell is infected.

Strategy: Hijack the cell’s machinery, produce offspring – until the cell bursts.

Virion vs. Virus – Why the Distinction Matters

In science, every detail counts – even whether a virus is „dormant” or actively invading a cell.

- Virion: The infectious particle outside of cells – the traveling form.

- Virus: The generic term – includes both phases, inactive and active.

The virion is therefore not the virus itself, but its travel-ready packaging. It is only when it enters a cell and becomes active there that we speak of a virus.

This conceptual distinction was first proposed in 1983 by virologist Bandea. Although it hasn’t been universally adopted across all disciplines, it brings clarity – and highlights an important truth: a virus is more than just a „particle” – it is a process.

1.1. Guardians of Nature: Viruses as Regulators of Balance

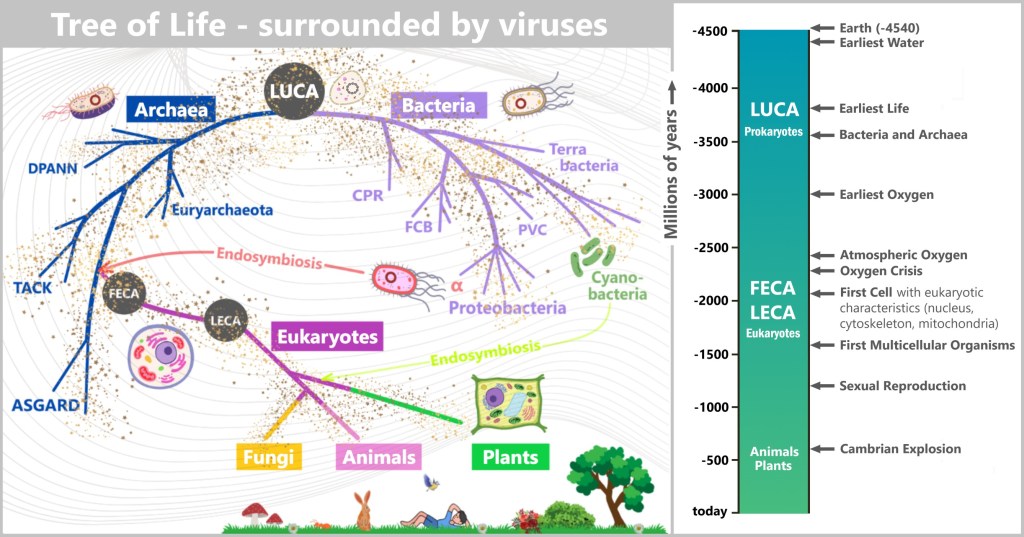

The word „virus” instantly sets off alarm bells for most people: influenza, COVID, HIV, Ebola – disease, danger, pandemic. But this image represents only a tiny fraction of the truth. Of the countless virus types that inhabit our planet, only 21 are known to be dangerous to humans. The rest? Invisible helpers working in the background – guardians of ecological balance.

So no need to panic: most viruses couldn’t care less about us. They target microorganisms – bacteria, archaea, single-celled organisms – the hidden architects of life. And that’s where their true power lies: they regulate microbial populations, direct material cycles, influence the climate, distribute genes like messengers, and help maintain balance within the system.

There’s hardly a place on Earth where they can’t be found. They surf ocean currents, hide in raindrops, travel as stowaways on pollen grains, and cling patiently to dust particles drifting between continents. Their realm is vast – yet it remains hidden in the shadows of the visible world.

Mind-Boggling Numbers

With an estimated 100 million species, viruses are among the most abundant biological entities on Earth. Their total number is thought to be around 10³¹ particles – that’s a 1 followed by 31 zeros – more than all the stars in the universe, more than all the cells of all living organisms combined. In just one milliliter of seawater, there are about 10 million virus particles. Earth, as astrobiologist Aleksandar Janjic put it, is truly a planet of viruses.

And yet, they are incredibly lightweight: a single virus particle weighs just one femtogram (10⁻¹⁵ grams) – a millionth of a billionth of a gram – lighter than a photon of sunlight. Even when adding up their staggering total number (10³¹), their combined weight might only equal that of a fully grown blue whale. And still: without them, no balance, no cycles – no life as we know it.

But what makes them an integral part of the ecosystem?

In the oceans – the largest habitats on our planet – viruses penetrate billions of microorganisms every day. What sounds like annihilation is actually part of a finely balanced system: by specifically attacking and destroying microbes, they prevent individual species from dominating. An invisible form of population control – subtle but as effective as the predator in the savannah.

And they do even more: when their host cells burst, they release valuable nutrients – carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus. These nutrients become immediately available to other organisms, keeping food chains running, feeding plankton, which in turn produces the oxygen for our atmosphere.

At the same time, viruses act as evolution boosters. They transfer genes from one organism to another – a natural gene transfer that enables new traits, promotes diversity, and sparks innovation long before we even knew about genetic engineering.

And so it becomes clear: viruses are not mere carriers of disease. They are intricate cogs in the machinery of nature – unseen, rarely noticed, but indispensable.

A look into various habitats reveals their impact.

🌊 In the World’s Oceans

Population Control: Deep beneath the water’s surface, a microscopic battle of planetary scale rages on: bacteriophages – viruses that specifically infect bacteria – eliminate up to 40% of marine bacteria every day. By doing so, they prevent explosive algal blooms that could turn entire oceans into oxygen-deprived dead zones.

Without these „microbe hunters”, our planet would have long since sunk under a shroud of algae.

📖 Additional Sources:

Viral control of biomass and diversity of bacterioplankton in the deep sea

A sea of zombies! Viruses control the most abundant bacteria in the Ocean.

The smallest in the deepest: the enigmatic role of viruses in the deep biosphere

Gene Smuggling: In the blue depths of the oceans, Prochlorococcus – a tiny cyanobacterium – performs a mighty feat: it produces about 10% of the world’s oxygen. Yet even this microscopic hero is under the control of even smaller puppeteers: cyanophages – viruses perfectly specialized to infect it. These viruses insert their own photosynthesis genes and compel the infected cell to cooperate. The result: the bacterium remains „operational”, continuing to produce energy – now in service of its viral occupants. This parasitic partnership illustrates the so-called Black Queen Effect: by taking over certain functions, viruses allow microbes to lose those functions themselves and specialize in other tasks.

An involuntary division of labor, orchestrated by viruses.

Dive Deeper: An impressive glimpse into the mysterious world beneath the ocean’s surface is offered by a video from the Schmidt Ocean Institute. It showcases how researchers, using cutting-edge technology, follow the traces of microbial life – and in doing so, also track down viruses.

But viruses don’t just play this regulatory role in water – they are equally active in other ecosystems.

🟫 In the Soil

Even beneath our feet, viral activity is in full swing: viruses keep dominant soil bacteria in check, ensuring that no single microorganism gains the upper hand. This invisible regulation safeguards the delicate balance of the nutrient cycle – the foundation of all growth.

Like invisible gardeners, they comb through the micro-life of the Earth, weeding out excess and creating space for diversity.

🌳 In the Plant World

Trees and fields have secret allies: plant viruses. Around every root network unfolds a hidden web of control, defense, and opposition. Some plant viruses specifically target harmful bacteria that would otherwise sicken the plant. Others stimulate the plant’s own immune system – and when microbes die, viruses break down their remains into fertile compost. Some plants even go a step further: they actively recruit protective viruses that patrol the root zone like microscopic bodyguards.

Without these microscopic alliances, many forests would be far more vulnerable to fungal overgrowth – and our crops would be left defenseless against attacks from the soil.

🔗 Viruses as components of forest microbiome

🪱 In the Gut Flora of Humans and Animals

A silent power struggle also unfolds within our intestines – and we benefit from it. Specialized gut viruses (bacteriophages) specifically target harmful germs like E. coli, helping to maintain a stable bacterial balance. They transfer protective genes between microbes – like secret data packets that fine-tune immune responses. Some viruses even dampen overactive immune reactions, preventing inflammation in the process.

Without these nano-sheriffs, harmful bacteria would overrun the gut within days.

🔗 Over 100,000 Viruses Identified in the Gut Microbiome

☁️ In the Atmosphere

High above our heads, the largest gene transfer on Earth takes place – a single storm can disperse up to 500 million virions per square meter across entire continents, forming the ultimate bio-invasion route. Thanks to their extreme resilience, viruses survive where others fail – in UV-soaked altitudes, icy clouds, and dry air. They travel via dust, sea salt, or plant droplets across oceans and continents. Some even influence precipitation patterns by interacting with clouds.

This atmospheric gene exchange transforms local mutations into global evolution – as if nature had invented its own internet.

🔗 Deposition rates of viruses and bacteria above the atmospheric boundary layer

⚡️ In Extreme Habitats

Even in hot springs, salt lakes, or beneath the Earth’s crust, viruses thrive – regulating local microorganisms and boosting their genetic diversity. In these hostile environments, such regulation is an essential survival strategy.

🔗 Viruses in Extreme Environments, Current Overview, and Biotechnological Potential

The Greatest Paradox in Biology: From billions of microscopic acts of destruction arises global balance. So the next time you fear a virus, remember: with every breath, you carry billions of these tiny entities – and they, in turn, carry you. A pact of life – as old as evolution itself.

„We live in a balance, in a perfect equilibrium”, and viruses are a part of that, says Susana Lopez Charretón, a virologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. „I think we’d be done without viruses.” [Why the world needs viruses to function]

„If all viruses suddenly disappeared, the world would be a wonderful place for about a day and a half, and then we’d all die – that’s the bottom line”, says Tony Goldberg, an epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. „All the essential things they do in the world far outweigh the bad things.” [Why the world needs viruses to function]

1.2. Viruses as Drivers of Evolution

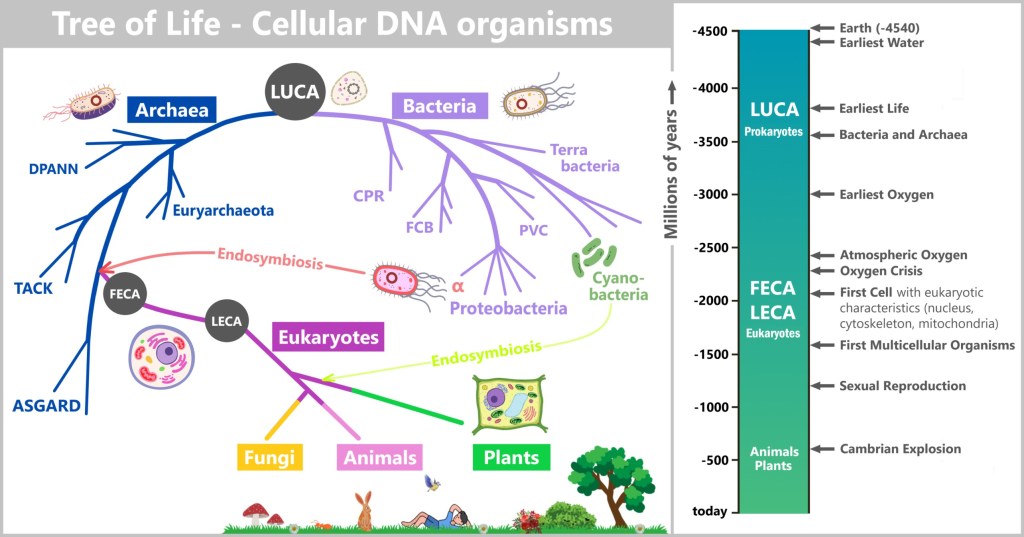

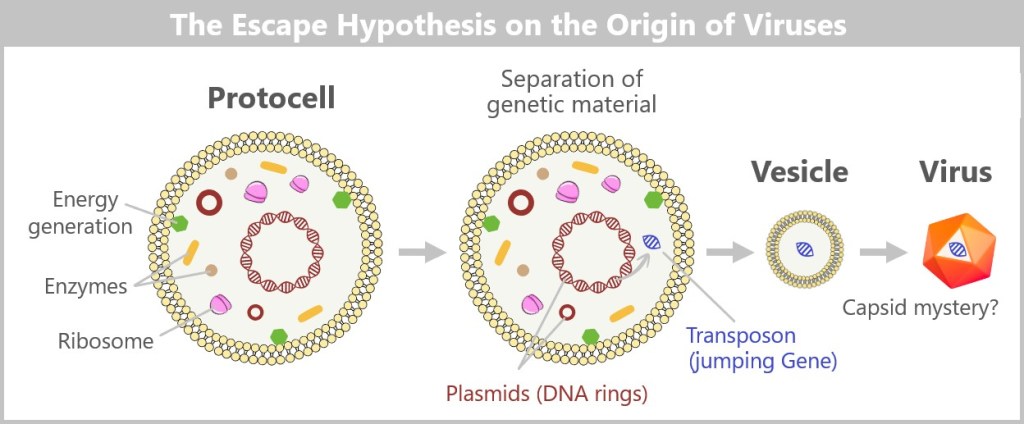

Long before dinosaurs roamed the earth, viruses were already up to mischief – shaping life as we know it today. Their tool: horizontal gene transfer, a biological copy-paste mechanism that enabled evolutionary quantum leaps.

For evolutionary biologist Patrick Forterre from the Pasteur Institute, viruses are the architects of life – without them, evolution might have taken a very different path.

(See also Spektrum der Wissenschaft: „The True Nature of Viruses”, ScienceDirect: „The origin of viruses and their possible roles in major evolutionary transitions” or „The two ages of the RNA world, and the transition to the DNA world: a story of viruses and cells”)

Genetic Sabotage with Lasting Effects

Viruses are masters of manipulation. When they infect a cell, they don’t just inject their own genetic material – sometimes their genes get integrated into the host’s genome and are passed down through generations. Supposed disruptors thus become creative gene architects.

A spectacular example: The placenta of mammals owes its existence to a virus. A viral envelope protein – originally designed to suppress immune responses – was incorporated into the gene pool and helped develop the barrier between mother and embryo. Without this „foreign” gene: no womb, no mammal.

But it goes even further: about 8% of the human genome comes from ancient retroviruses that once embedded themselves into our DNA – silent witnesses of ancient infections that may still influence us today. Even our brain might carry viral traces – for example, genes crucial for the development of the cortex.

Aren’t we all a bit of a virus?

CRISPR, celebrated today as a revolutionary gene-editing tool, traces back to an ancient bacterial defense system – a genetic archive of past viral attacks from which bacteria learn to defend themselves against new enemies.

Some scientists even ask: Could viruses have played a role in the origin of life itself? Certain hypotheses suggest that virus-like particles may have been the first molecules capable of storing and transmitting genetic information – a fundamental prerequisite for life.

The irony of fate: We fear viruses as bringers of death – yet without them, we might never have come into existence.

1.3. Do Viruses Really Exist?

Despite their immense importance, there are always doubts about the existence of viruses. How can we be sure that they are real? This question cannot be answered by simple observation – viruses elude our naked eye and only reveal themselves through indirect traces and specialized detection methods.

To get to the bottom of this question, we first need to understand how viruses act: What mechanisms do they use to replicate? How do they interact with their hosts? And above all, what scientific methods are available to visualize and detect them?

The search for these answers leads us into a fascinating world of advanced technologies and decades of research. In the chapters to come, we will explore step by step how scientists detect viruses – bringing us closer to answering the essential question: Do viruses really exist?

2. Viral Mechanisms Illustrated by Influenza

Let’s begin by taking a closer look at how viruses „hijack” their host cells and exploit them for reproduction. A prime example of this is the influenza virus – not only because it is one of the most thoroughly studied viruses, but also because it vividly demonstrates how viruses manipulate cells and spread. The mechanisms it employs offer us an ideal insight into the mysterious world of viruses and their complex interactions with their hosts.

2.1. How the Influenza Virus Travels

2.2. The Architecture of the Influenza Virus

2.3. The Infection Process of the Influenza Virus

2.4. The Adaptability of the Influenza Virus

2.5. Entry and Exit Routes of the Influenza Virus

2.6. Mostly Localized Mucosal Infection

2.7. Viral Strategy: Efficient Replication Without Rapid Cell Destruction

2.8. Destruction of the Host Cell

2.9. Self-Limiting Dangerous Viruses: Why They Rarely Cause Pandemics

2.10. Why Does the Virus Make Some People Sick and Others Not?

💡Note: The following chapters build upon basic knowledge of cells, the difference between DNA and RNA, proteins, and cellular processes such as protein biosynthesis. If these topics are still new to you, it may be helpful to take a look at Chapters 2, 3, and 4 of the treatise „The Wonderful World of Life” or similar introductory texts.

Chapter 2: The Cell – The Fundamental Building Block

Chapter 3: Proteins – The Building Blocks of Life

Chapter 4: From Code to Protein – Cellular Mechanisms

2.1. How the Influenza Virus Travels

The influenza virus is constantly on the move – an invisible jet-setter with astonishing transmission routes: sometimes it travels first class via a sneeze cloud, other times it hitchhikes over door handles.

Droplet flight – first class through the air

One sneeze is enough: up to 40,000 virus-laden droplets shoot through the air – like a mini missile strike on the surroundings (range: up to 2 meters!).

Smear attack – the secret handshake

Door handle, elevator button, keyboard – the virus chills on surfaces, sometimes for hours. One touch, one swipe of the face – and it has already gained access via a hand-to-face trick.

Mission: Respiratory Tract – Viral Invasion

Once inside the respiratory tract, the virus launches its assault on epithelial cells:

Preferred target: Mucosal cells in the nose, throat, and bronchi.

Why? There are plenty of favourite receptors here – perfect docking sites.

Result: Within hours, it hijacks the cell’s machinery and begins producing new viruses.

From the outside, it looks like a speck of dust with bad intentions – but upon closer inspection, the influenza virus reveals itself as a highly complex nanomachine. To understand how it hijacks cells and constantly mutates, it’s worth taking a closer look inside.

2.2. The Architecture of the Influenza Virus

The influenza virus is the reason we find ourselves bedridden with fever, cursing „the flu”. Of the three strains (A, B, and C), Type A is the most dangerous globetrotter: as shape-shifting as an actor and as unpredictable as April weather. Types B and C, on the other hand, are more „down-to-earth” – less variable and generally less dangerous. Yet all of them share the same ingenious structural blueprint (see illustration below).

The virus particle – a mere 80 to 120 nanometers in size – is a master of survival, resembling a tiny, spherical nano-submarine (sometimes oval-shaped). Inside: its viral genetic material made of RNA – but with a special trick!

While we often think of RNA or DNA as a single, unbroken strand, viruses have different DNA and RNA structures. Some have a single continuous molecule, others carry their genetic material divided into several RNA segments.

The Command Center: Genome in 8 Segments

The influenza virus is based on a modular design: it uses 8 separate RNA segments – like a construction kit whose parts can always be recombined – perfect for surprises!

These RNA segments vary in length – from compact mini-modules to XXL construction manuals – and yet they are perfectly harmonised. To prevent them from getting lost like loose pages in the wind, each segment is carefully packaged: every strand is wrapped in a sheath of nucleoproteins (NP), like precious scrolls in protective foil. But the NP envelope is more than just protection: it assists the viral machinery to precisely read, copy and pass on the genetic information.

The toolbelt: Polymerase complexes

In addition, the virus brings its own 3D printers – the RNA polymerases (composed of the subunits PB1, PB2, and PA). These are firmly attached to the RNA segments, like craftsmen carrying their tools on a belt.

The RNP Complex – the Heart of the Virus

Each RNA segment + nucleoproteins (NP) + polymerase forms a ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP) – a perfectly organized unit: the virus’s command center. All eight – neatly packed and ready for action – like a portable toolbox for taking over the cell.

The Lipid Envelope – the Stolen Cloak of Invisibility

The virus steals its outer layer directly from the host cell: a lipid bilayer – identical to the cell membrane, making it the perfect disguise! Just beneath it lies the matrix protein M1 – the molecular scaffolder that holds everything together. It connects the outer envelope with the inner complex and ensures the virus keeps its shape – like a support frame beneath the cloak.

The Spikes: Key & Scissors

Embedded in the viral envelope are crucial surface proteins that protrude like tiny spikes or grasping arms. These are called „spikes”. The influenza virus has two especially important spikes that help it infect cells: Hemagglutinin (HA) and Neuraminidase (NA).

🔑 HA – The Door Opener: Acts as a key to dock onto the host cell.

→ 18 known variants (H1–H18)

✂️ NA – The Escape Helper: Breaks the connection to the host cell so the virus can move on.

→ 11 variants (N1–N11)

Virus Types: A Numbers Game

The combination of HA and NA determines the strain:

- H1N1 (swine flu)

- H5N1 (avian flu)

- H3N2 (seasonal flu)

Like car license plates: HA/NA codes reveal which „model” is on the move – just without road safety inspection!

2.3. The Infection Process of the Influenza Virus

a) Attachment of the virus to the host cell (Adsorption)

b) Entry into the cell (Endocytosis)

c) Release of the viral genetic material (Uncoating)

d) Viral replication – The molecular factory

e) Assembly of new virus particles

f) Budding and release of new viruses

a) Attachment of the Virus to the Host Cell (Adsorption)

The surface of the respiratory tract is lined with a dense epithelium of mucosal cells. These cells carry sialic acid residues on their surface – sugar molecules that play a central role in cell communication and immunological self-recognition (see chapter „SELF Markers: Sialic Acids” in „The Wonderful World of Life”).

The influenza virus hijacks this mechanism: its surface protein hemagglutinin (HA) specifically binds to the sialic acid of the host cell – a classic lock-and-key interaction that initiates the virus’s entry.

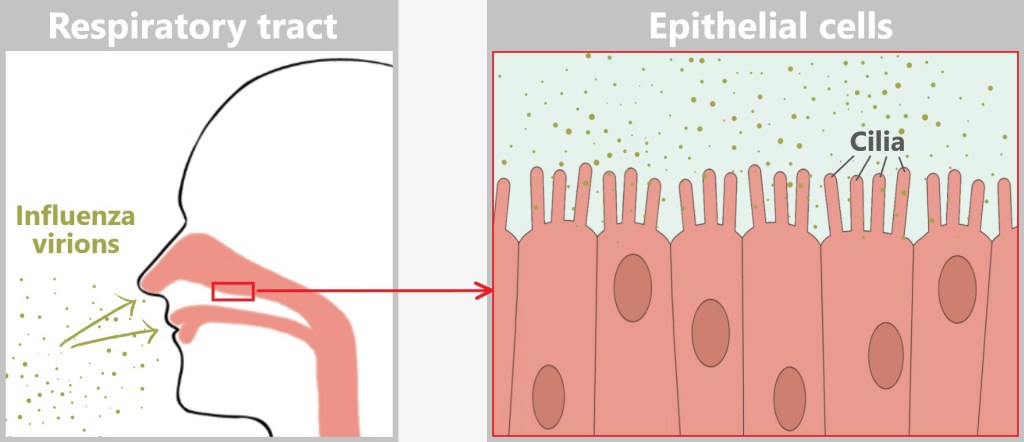

Before the influenza virus can infect a cell, it must first attach to the host cell – a crucial step in the infection process. However, the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract are not defenseless: their motile cilia (tiny hair-like structures) transport foreign particles such as dust, bacteria, or viruses away before they can reach the cell surface.

The illustration shows the relative sizes at the cell surface. The cilia are 5–10 micrometers long, while the mucus layer has a thickness of 10–100 micrometers. At just 80–120 nanometers, the virus particle is tiny. It must quickly reach a cell before the cilia carry it away.

Between the cilia, there are exposed areas of the cell surface where the virus can make direct contact. The sialic acid residues (1 nanometer) on the host cell membrane serve as docking sites for the HA protein (13 nanometers) of the virus, which is large enough to reach these structures. This allows the virus to penetrate the mucus layer and bind to the host cell.

b) Entry into the Cell (Endocytosis)

The influenza virus is a master of disguise: by binding its hemagglutinin to sialic acid residues, it mimics a harmless nutrient molecule. The host cell falls for the trick and initiates its standard uptake mechanism – endocytosis.

What follows is a molecular spectacle:

The cell membrane folds around the attached virus – triggered by signaling molecules normally responsible for nutrient uptake. Like a closing trap, an indentation forms that fully engulfs the virus. With a final „snap” of the membrane, an endosome is formed – a transport vesicle that now innocently shuttles the intruder into the cell’s interior.

What the cell registers as harmless transport turns out to be a Trojan horse.

The virus is now inside the cell – still enclosed within the endosome – but ready to unfold its innermost potential.

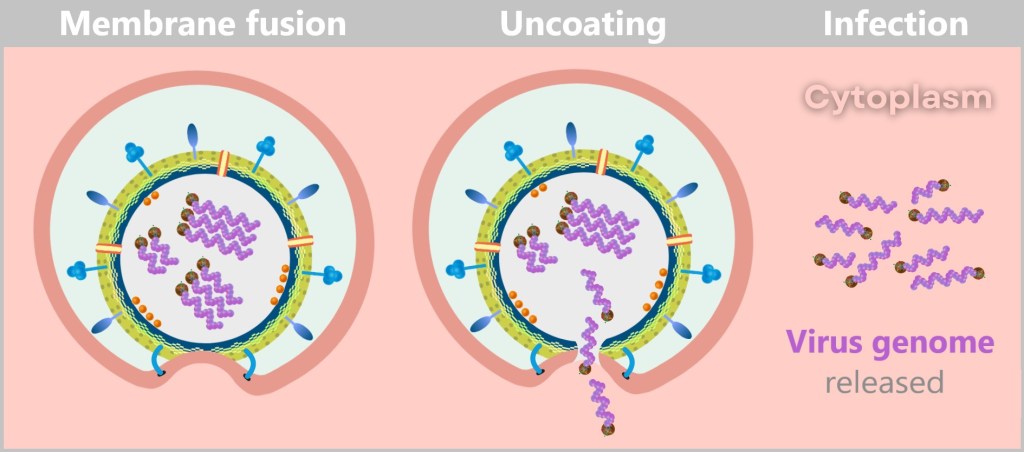

c) Release of the Viral Genetic Material (Uncoating)

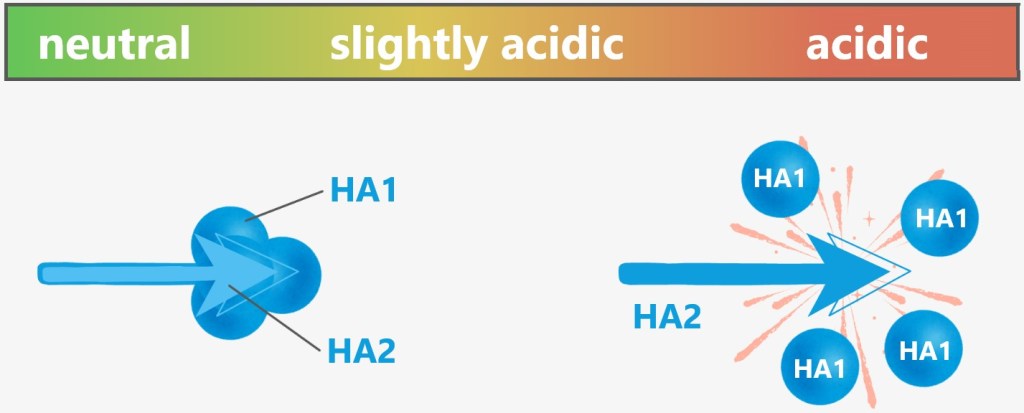

The early endosome matures into a late endosome – a site where the cell typically degrades unwanted intruders. Proton pumps lower the pH by transporting protons (H⁺ ions) into the interior, creating an acidic environment intended to activate digestive enzymes.

The acidic trick

But the influenza virus has a brilliant counterplan: the acidic environment triggers a dramatic transformation of the viral hemagglutinin (HA). The protein splits – its binding domain HA1 is cleaved off, and the fusion domain HA2 is exposed.

This fusion domain, HA2, is hydrophobic – it avoids water – and rams itself like a grappling hook into the endosomal membrane (see illustration below).

At the same time, the M2 protein – a viral ion channel – acts as a secret accomplice and opens the floodgates: protons flow into the virus interior, loosening the packaging of its genetic material.

Now, HA2 pulls the viral membrane and the endosomal membrane together with relentless force. The two lipid membranes fuse – a process known as membrane fusion. This occurs because the lipid molecules in the membranes are flexible and can rearrange themselves to form a continuous bilayer.

This fusion creates a pore – the gateway to freedom for the viral genome. With one final, elegant push, the viral RNA slides into the cytoplasm. The uncoating process is complete.

The cell has no idea that it has just released the blueprint for its subjugation.

Through membrane fusion and uncoating, the viral envelope is dissolved, releasing the genome and initiating the infection.

Why is the virus not degraded?

The virus is not degraded by the cell’s digestive enzymes because the release process happens quickly – before the degradation mechanism (activation of digestive enzymes) can take effect. The virus exploits the drop in pH and the changes within the endosome to rapidly escape by triggering membrane fusion, releasing its genome directly into the cell’s cytoplasm. This „escape” from the endosome is faster than the cellular breakdown process, which is why the virus is not decomposed.

d) Viral Replication – The Molecular Factory

The viral RNA does not arrive unprotected – it travels in high-tech armor: wrapped in protective nucleoproteins (NP) and equipped with viral polymerase, each of the eight RNA segments forms a highly organized ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP). These molecular command units are perfectly equipped for their mission:

- The nucleoproteins act like armor – shielding the RNA from cellular defense systems.

- The polymerase is the Swiss army knife of the virus – a tool for copying (replication) and translating (transcription) in one.

As soon as the ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) are released in the cytoplasm, the systematic takeover of the cellular production lines begins – the virus factory goes into operation. The genome takes on two central tasks: On the one hand, it serves as a blueprint for the production of viral proteins (Protein synthesis), on the other hand, it is itself replicated (Genome replication) – so that each new virus particle is given its own copy of the genetic material along the way.

Protein synthesis: The viral genome serves as a template for the synthesis of the proteins needed to assemble new virus particles.

Genome replication: At the same time, the viral RNA is replicated to provide the genetic information for new viruses.

While most RNA viruses remain in the cytoplasm, influenza has a clever trick up its sleeve: it hijacks the cell nucleus. Why? Because there, it finds optimal conditions for replicating its RNA.

The journey there, however, is anything but straightforward. The RNPs manipulate the cellular transport system by presenting fake import signals – molecular entry passes that grant them access to the nucleus. Cellular importins, normally responsible for transporting the cell’s own proteins, thus become unsuspecting smugglers. In a feat of biological deception, the viral RNPs are escorted straight into the cell’s control center.

In the cell nucleus, the RNPs finally unfold their full potential. The viral polymerase begins its double role:

- Copying the viral RNA (replication) → blueprint for new viruses

- Producing viral mRNA (transcription) → building instructions for protein synthesis

As this process is particularly sophisticated, each step is described in detail below.

1️⃣ Activation of the RNA polymerase – Here we go

The viral polymerase needs a molecular ignition spark to become active. And it finds this in the cell nucleus: a biochemical special zone that differs significantly from the cytoplasm. High concentrations of nucleotides, ions and nucleus-specific factors send a clear signal: „This is the place to start!” Only in this environment does the polymerase come to life. Without this molecular wake-up call, it remains in a dormant state – camouflaged as a harmless cellular component.

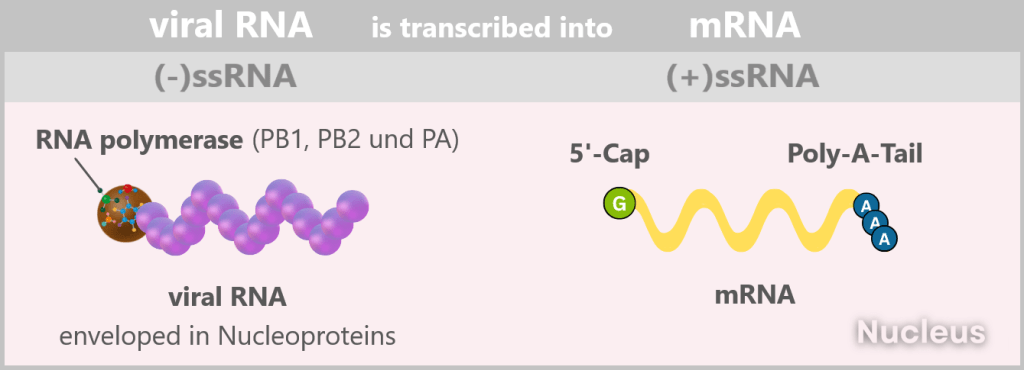

2️⃣ Initial situation: (-)ssRNA – A Genome in Mirror Writing

The genome of the influenza virus is a master of disguise. Instead of presenting itself as a readable blueprint, it appears more like a riddle in mirror writing: eight separate RNA segments, negatively polarized, lacking all the usual hallmarks of a cellular message. No sender, no letterhead, no stamp. To the cell, it’s not a message – it’s biological noise.

In scientific terms:

The viral genome consists of eight segmented single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) with negative polarity: (-)ssRNA. „Negative” means that this RNA is the complementary template to the mRNA (i.e. mirror-inverted) and therefore not directly readable.

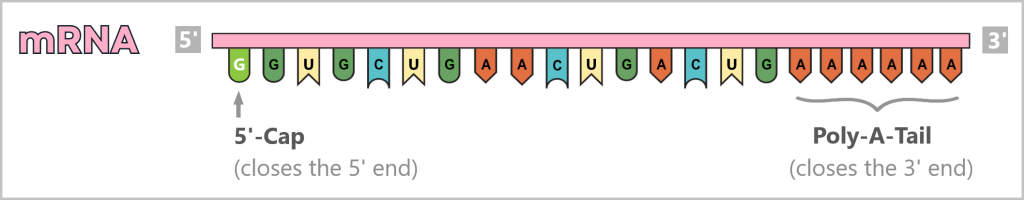

In addition, it lacks two crucial identifying features: the 5′ cap (a kind of molecular start button) and the 3′ poly-A tail, which protect and identify a normal mRNA.

Why so complicated?

Because it’s brilliant.

With this molecular masquerade, the virus achieves two things:

Staying invisible: The (-)ssRNA is not immediately recognized as a threat by the cell’s immune system. If the viral genome were already in the form of mRNA, the cell’s alarm systems would be triggered right away.

Full control over production: The virus doesn’t beg for help from the host’s enzymes. Because only the virus’s own RNA polymerase can convert the (-)ssRNA into readable mRNA, the virus can precisely control:

➤ When mRNA is produced.

➤ How much of it is produced.

➤ Which segments are prioritized.

In short: What looks like a cryptic puzzle is actually a highly precise control mechanism – a blueprint that only reveals itself when the viral machinery is ready – and the immune system is still asleep.

3️⃣ From (-)ssRNA to (+)ssRNA (the mRNA)

The viral polymerase is ready to transcribe the (-)ssRNA into readable mRNA – but the start button is missing. Without the 5′-cap, the machinery remains silent.

The solution? Theft at nano level.

This ingenious trick is called cap-snatching.

The Coup in Detail

The polymerase subunit PB2 prowls through the cellular mRNAs like a cunning thief searching for the most valuable jewel. Its target: the 5′ cap, the universal „seal” for cellular protein factories. Its accomplice, PB1 – the „molecular scissors” – cuts off the cap along with 10–15 nucleotides – a perfect primer for viral transcription. The stolen cap is attached to the viral RNA. The cell believes it has a legitimate mRNA and starts producing viral proteins. Meanwhile, the capped host mRNA is degraded – causing the collapse of the cell’s protein production.

At the same time, the viral mRNA receives a poly-A tail at its 3′ end, which stabilizes and protects it.

Why this trick is so brilliant

✅ Energy-saving: The virus uses existing resources – no effort needed to synthesize its own cap.

✅ Sabotage: The degradation of cellular mRNAs cripples the host’s defense.

✅ Camouflage: The stolen cap disguises viral mRNA as a „harmless” cellular message.

The Consequences of the Heist

- The cell loses its own blueprints – and now produces viral proteins at full speed.

- The virus gains twice: rapid replication and weakening of its adversary.

This process is a classic in virology – a prime example of how viruses turn their host cells into puppets.

In the end, numerous „naked” +ssRNA strands are produced in the cell nucleus, which are used directly as mRNA for translation, i.e. for viral protein production and genome replication.

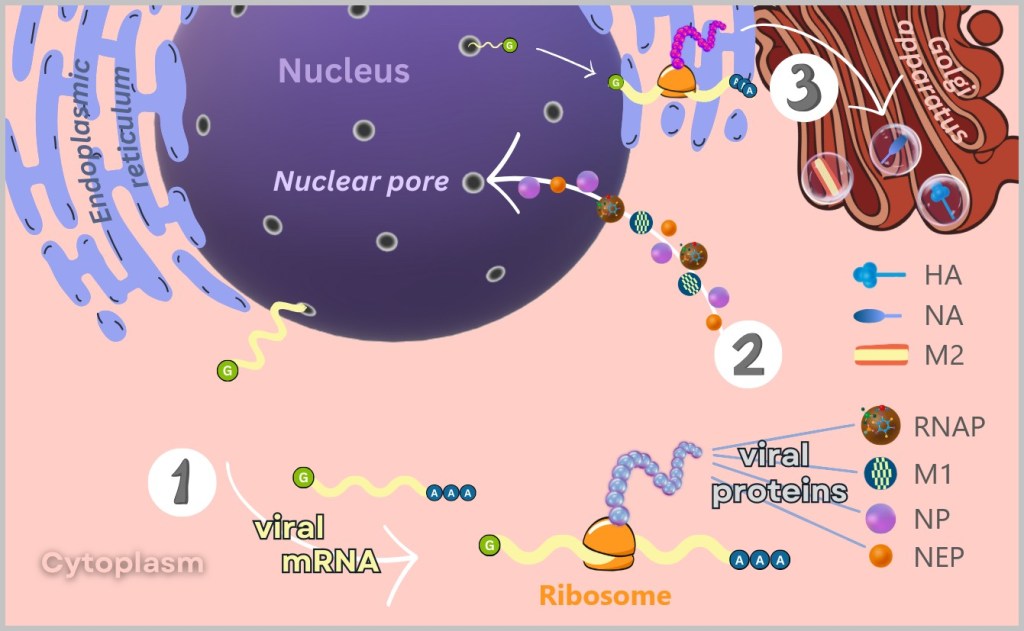

4️⃣ The virus production is running hot

The freshly capped viral mRNAs exit the nucleus – equipped with a stolen signature and a poly-A tail. In the cytoplasm, ribosomes are waiting, unsuspectingly executing the enemy’s blueprints.

The prey: an entire protein factory

The ribosomes churn out viral proteins on an assembly line – including:

Haemagglutinin (HA): The key to cell entry – the indispensable door opener.

Neuraminidase (NA): The liberator of new viruses – the sharp molecular scissors.

Matrix protein (M1): The stable envelope for the virus interior – the scaffold builder.

Ion channel protein (M2): The pH guardian – regulates the acidic environment in the virus.

RNA Polymerase (RNAP): The copying machine – a viral printing press.

Nucleoprotein (NP): The bodyguards – package and protect the RNA segments.

Nuclear Export Protein (NEP): The dispatcher – handles the export of viral RNPs from the nucleus.

These freshly produced proteins are ready for the final act: the assembly of new virus particles.

5️⃣ Return to the Nucleus

After being produced in the cytoplasm, most viral proteins make their way back to the nucleus – the command center of viral replication. The only exceptions are the surface stars: hemagglutinin (HA), neuraminidase (NA), and the ion channel protein M2, which operate directly at the cell membrane.

The remaining viral actors return to headquarters to pick up new orders and prepare for the final mission.

1) At free ribosomes in the cytoplasm, the mRNA is translated into viral proteins such as RNA polymerase, matrix proteins (M1), nucleoproteins (NP), and nuclear export proteins (NEP).

2) These proteins then migrate back into the nucleus to participate in the replication and packaging of the viral genome.

3) The surface proteins (HA and NA) and the ion channel protein (M2) are synthesised at the membrane-bound ribosomes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). After their production, these proteins are transported to the Golgi apparatus, where they are further modified and prepared for incorporation into the viral envelope.

6️⃣ The Genome Copy Factory: (+)ssRNA → new (-)ssRNA

While viral proteins are being mass-produced in the cytoplasm, a covert operation „Genome Replication” unfolds in the nucleus:

Newly formed RNA polymerases grab the freshly synthesized (+)ssRNA strands and transcribe them back into viral mirror-image RNA – producing new (−)ssRNA strands. The polymerase remains bound as an integrated printing press for future rounds.

Nothing is left to chance: Even as the genetic code is being reverse-transcribed, nucleoproteins (NP) coat the emerging (−)ssRNA – it doesn’t spend even a second „naked” – eliminating any risk of cellular surveillance. The freshly copied RNA segments are immediately packaged and sealed: Together with the polymerase, they form complete ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) – fully equipped genome modules, ready for the next generation of virus.

Once the eight segments are packaged, the viral logistics team takes over: NEP (nuclear export protein) and M1 (matrix protein) tag the RNPs for export. They escort them through the nuclear pores – the cell’s heavily guarded gateways – directly into the cytoplasm. Mission: assembly hall.

1) The viral RNA polymerase uses the (-)ssRNA as a template to synthesize a complementary (+)ssRNA.

2) This (+)ssRNA then serves as a template for the renewed synthesis of viral (-)ssRNA – the actual genetic material for new virus particles.

3) Already during synthesis, the new (-)ssRNA is coated with nucleoproteins (NP) and packaged with polymerase, M1, and NEP into the so-called RNP complex – stable and ready for export.

4) The completed RNP complexes exit the nucleus through the nuclear pores and migrate into the cytoplasm – where the assembly of new viruses soon begins.

Like a clandestine printing shop in the back room: The polymerase continuously produces copies, the NP proteins immediately package them, and smugglers (NEP/M1) discreetly sneak them out.

While the cell unsuspectingly burns through its resources, the real showdown is still ahead…

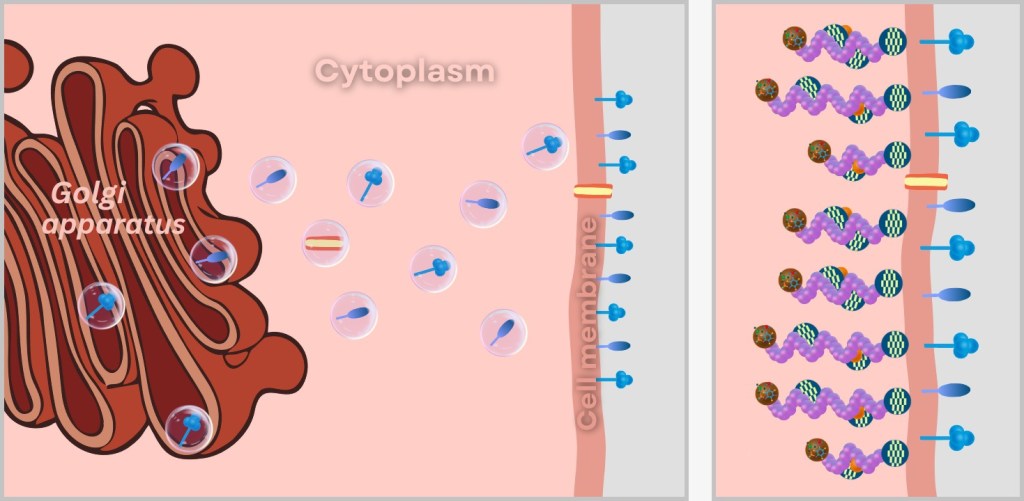

e) Assembly of New Virus Particles

Once all the components have been produced, the coordinated final assembly begins in the cytoplasm – a process as precise as the construction of a space probe: every part has to fit perfectly, otherwise nothing will lift off.

The surface proteins HA & NA travel through the Golgi apparatus – the cell’s „packaging department” – to the cell membrane (see lower left illustration). There, they anchor themselves in the lipid bilayer like door handles and rescue scissors protruding from the envelope of a future virus particle.

The ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) also set out on their journey, already in tow of the matrix proteins M1, which act as logistics managers. Their task: to reliably navigate the valuable cargo to the membrane regions equipped with HA and NA (see lower right illustration).

At the cell membrane, the viral puzzle comes together piece by piece: The RNPs arrange themselves beneath the membrane studded with HA and NA. The matrix proteins assist in bringing the RNPs into contact with specific regions of the cell membrane.

Left: Incorporation of viral surface proteins (HA and NA) and the ion channel protein (M2) into the cell membrane.

Right: Transport of ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) to the cell membrane and their attachment to the forming viral envelope.

And now – drumroll please – everything is set for the grand breakout!

f) Budding and Release of New Viruses

A protrusion forms on the cell membrane – like a soap bubble with a deadly cargo. But what looks so playful is actually precise choreography:

➤ Viral proteins push outward, causing the lipid bilayer to curve into a perfectly shaped „virus package”.

➤ Matrix proteins (M1) stretch the membrane like a trampoline – stable, but flexible enough for the jump.

➤ The host lipids close to form a camouflaged envelope – the virus packages itself.

But it is not yet free. Sialic acid tethers lurk on the cell surface – normally HA’s favourite anchorage. Without resistance, the virus would stick like chewing gum under the sole of a shoe.

Neuraminidase (NA) steps in: the molecular scissors slice through the sialic acid residues on the cell surface. No sticking, no turning back – a clear path to the next cell.

Like a jailbreak with style: M1 loosens the bars, NA cuts the alarm wires – and they’re gone! Final countdown for the virus crew! All systems go – HA/NA check, RNPs check, lipid armor check. Launch sequence initiated in 3…2…1… Budding!

Left: Budding of the virus at the cell membrane. Right: Release of the newly formed virus particle.

The following video provides a clear and accessible summary of the replication cycle of the influenza virus.

After a host cell is infected by a single influenza virus, hundreds to thousands of new virus particles are typically produced. The exact number can vary and depends on several factors, such as the virus strain, the type of host cell, and the cellular conditions.

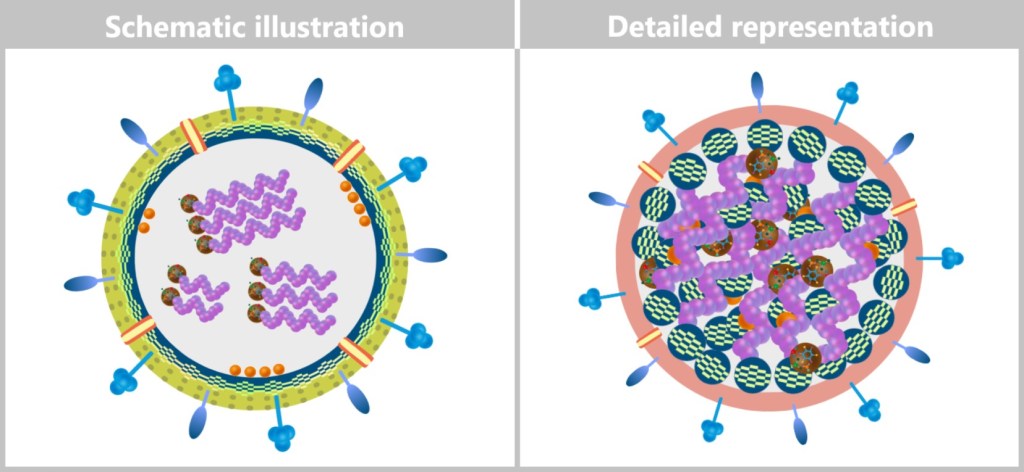

Simplified and Realistic Representation of the Virus Structure

In the initial illustrations of this text, the structure of the influenza virus was simplified for better clarity (see bottom left image). In these illustrations, the matrix protein is shown as a spherical, mesh-like ring structure surrounding the viral genome. This simplified representation is intended to make the complex processes of viral replication easier to understand.

Left: Schematic illustration to clarify the structure of the virus.

Right: More detailed schematic representation of the virion structure.

In the following illustrations, however, the structure of the new virions is depicted in a way that more closely reflects biological reality. The matrix proteins are not shown as a continuous ring, but are located in individual units that both bind to the inner lipid layer and are loosely linked to the ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs). In addition, the colouring of the lipid layer reflects the origin from the cell membrane of the host cell (see upper right figure).

The RNPs representing the viral genome are arranged inside as a loose bundle – not strictly parallel, but flexibly organized with ends oriented in different directions. The matrix proteins (M1) hold this bundle together and connect it to the lipid layer, giving the virion its shape and stability.

2.4. The Adaptability of the Influenza Virus

Viruses – especially RNA viruses like the influenza virus – mutate extraordinarily fast. The reason lies in their error-prone replication machinery: the viral RNA polymerase lacks a mechanism to correct copying errors, unlike DNA replication in human cells. As a result, random mutations – small changes in the virus’s genetic material – occur with each replication cycle.

Within an infected person, this process produces a multitude of slightly different virus particles. Most mutations are neutral, meaning they neither affect the virus’s function nor its ability to replicate. However, some mutations are disadvantageous, causing the virus to replicate less efficiently or lose infectivity entirely – these variants quickly disappear through natural selection.

But some mutations give the virus a survival advantage, especially when they affect the surface proteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). These proteins are key targets of the immune system: the body produces antibodies that specifically bind to them and neutralize the virus. However, if the structure of HA or NA changes due to mutations, the antibodies recognize the virus less effectively. The virus essentially becomes „invisible” to the immune defense and can continue to replicate and spread.

This constant adaptation explains why influenza viruses cause new waves of infection every year and why it is challenging to develop long-lasting vaccines against the flu.

The influenza virus does not exist as a fixed genetic entity but rather as a so-called mutant cloud (quasispecies) – a dynamic population of viral variants arising through continuous mutations. This genetic diversity is key to its survival: natural selection ensures that the variants most successful under the given conditions prevail. This high adaptability of the influenza virus vividly demonstrates how evolution occurs in real time.

The influenza virus must constantly change through mutations to continue existing as the flu virus. The high mutation rate leads to a multitude of slightly different viral particles within an infected person.

2.5. Entry and Exit Routes of the Influenza Virus

Influenza viruses use the mucosal surfaces of the respiratory tract as their entry point, since mucous membranes form the boundary between the external environment and the inside of our body. Many viruses initiate infection by interacting with the epithelial cells of these mucous membranes in order to spread efficiently within their host. [Virus Infection of Epithelial Cells]

As shown in the illustration below, the influenza virus enters the respiratory tract via the air – reaching the nose, throat, and lungs – and binds to the apical side (upper surface) of the epithelial cells, which faces the external environment. This apical side is covered with fine, hair-like structures called cilia, which help transport mucus and foreign particles. The opposite, basolateral side of the cell faces the underlying tissue and is connected to the basement membrane, anchoring it to the connective tissue.

The release of newly formed influenza viruses also occurs specifically at the apical side. This arrangement allows the viruses to spread into the surrounding environment – such as through droplets expelled by coughing or sneezing – thereby easily infecting new hosts. This apical release represents an evolutionary advantage, as it significantly enhances transmission efficiency.

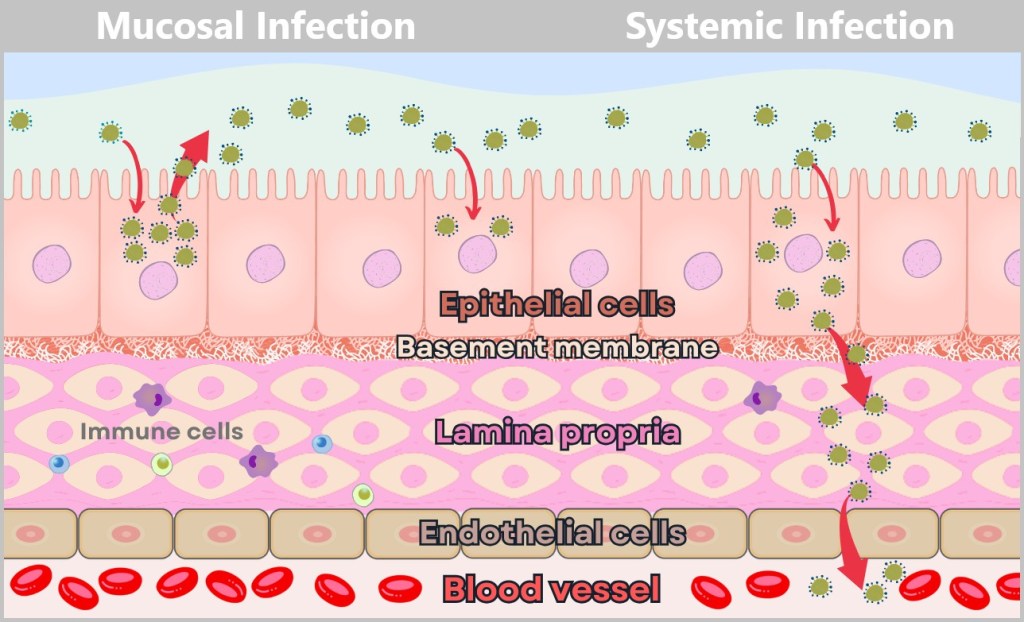

2.6. Mostly Localized Mucosal Infection

Influenza viruses are specialized for infections of mucosal surfaces. As a result, their infection typically remains localized to the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, meaning it is confined to a mucosal infection. The virus spreads from cell to cell along the apical side of the epithelial layer, without penetrating deeper tissue layers. Even when the infection progresses from the upper respiratory tract down to the lungs, it remains limited to the mucosal surface.

The basolateral side of epithelial cells usually remains untouched, as it plays no role in viral transmission. If the virus were to exit the host cell from the basolateral side, it could spread into the surrounding tissue and ultimately enter the blood or lymphatic system, potentially leading to a systemic infection. However, for influenza viruses, this would be disadvantageous: they would face stronger immune defenses and their transmission via the respiratory tract would become more difficult.

In rare cases – particularly in severely immunocompromised individuals – the virus can break through the epithelial barrier and invade the underlying tissue as well as blood or lymphatic vessels, leading to a systemic infection.

The mucosa consists of several layers: Epithelial cells form the outer protective layer, the basement membrane acts as a thin barrier, the lamina propria supports with connective tissue and immune cells, endothelial cells form the walls of blood vessels, and the blood vessel leads into the interior of the body.

Left – Mucosal infection (limited to the mucosal surface): The virus infects epithelial cells exclusively via the apical side. It remains within the mucosa, spreading from cell to cell along the apical surface. The basement membrane and underlying tissues such as the lamina propria remain intact. A mucosal infection is locally restricted and favors transmission via mucosal surfaces, such as the respiratory tract.

Right – Systemic infection (spread through the bloodstream): The virus enters the epithelial cells on the apical side but exits them via the basolateral side. It breaches the basement membrane and moves through the lamina propria, either by migrating or infecting cells there. Eventually, it reaches a blood vessel by passing through gaps between endothelial cells or by directly infecting the endothelial cells. Entry of the virus into the bloodstream marks the transition to a systemic infection. A systemic infection is critical because the virus can then spread throughout the body via the blood, potentially damaging vital organs such as the lungs, heart, or brain.

2.7. Viral Strategy: Efficient Replication Without Rapid Cell Destruction

Some viruses – including influenza viruses – are surprisingly economical: instead of destroying their host cell immediately, they exploit its resources as efficiently as possible. Why burn down the apartment if you can live rent-free for months? As long as the cell remains intact, it provides everything the virus needs for replication: energy, enzymes, building blocks. The immune system also notices something’s wrong only later – because if nothing’s on fire, no alarm is triggered. This strategy prolongs the life of the infected cell, delays the immune response, and maximizes the production of new viruses.

Virus wisdom: The best parasites stay under the radar!

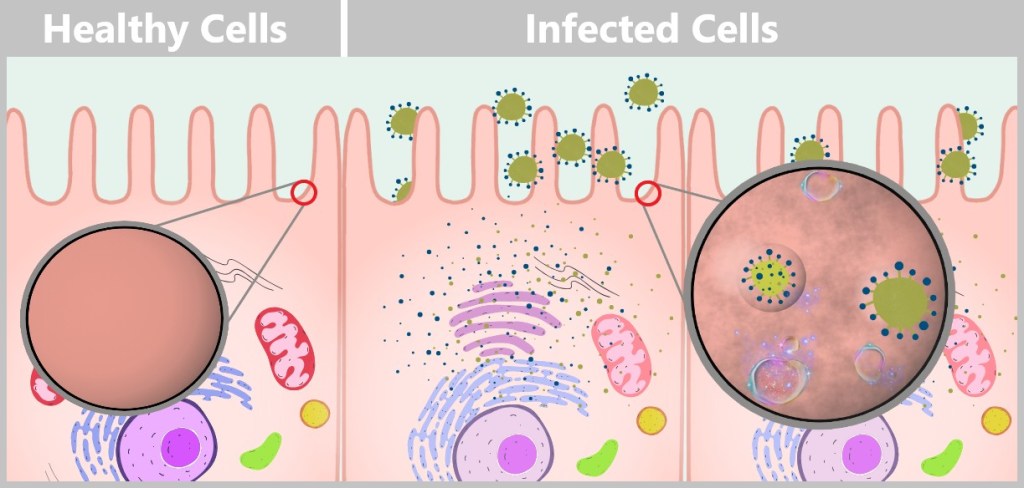

2.8. Destruction of the Host Cell

What starts as cunning protection ends in molecular burnout: the infected cell ultimately suffers cell death. This occurs when the cell is either overloaded and structurally damaged by the massive production of viruses, triggered to enter programmed cell death (apoptosis) by cellular defense mechanisms, or deliberately eliminated by the immune system. These characteristic changes in the host cell caused by the virus are referred to as cytopathic effects (CPE). This entire process can take place within as little as 24 hours after infection.

To better understand cell death caused by influenza viruses, let’s examine the three mechanisms by which the host cell is ultimately destroyed.

a) Overload and structural damage

b) Apoptosis: programmed cell death to combat the virus

c) Immune response: Destruction by the immune system

a) Overload and structural damage

The virus takes over the cellular processes to produce its own components. With each new generation of viral proteins and RNA, the cell’s energy and resource capacity become increasingly depleted. Since the cell practically works only for viral replication, its own vital functions come to a halt. The cell becomes a squeezed lemon – ribosomes run hot, mitochondria collapse.

Left: Healthy cell with fully functional cellular machinery. The cell’s own mRNA (orange) is read by ribosomes to produce proteins necessary for cellular functions. The cell displays vibrant staining, indicating full resource capacity and energy availability.

Right: Virus-infected cell, heavily burdened by the production of viral components. The viral mRNA (yellow) increasingly displaces the cell’s own mRNA, and the ribosomes predominantly read viral instructions for virus replication. The pale staining of the organelles symbolizes the depletion of energy reserves and the overload of the cell.

During budding at the cell membrane – when new virus particles exit the cell – the membrane is repeatedly pierced and deformed. This process ultimately leads to the loss of membrane integrity, causing the cell to lose its stability and protective functions. The cell eventually dies due to relentless resource depletion and structural breakdown resulting from virus release.

During budding, the cell membrane forms small protrusions from which new viruses are released. Each budding event removes tiny portions of the membrane’s lipid bilayer, as the newly forming viruses use the host cell’s membrane material for their envelope. After repeated viral release, the membrane becomes significantly thinned and structurally weakened, often showing deformations and irregularities. The constant stress from budding makes the membrane more porous and vulnerable. The cell increasingly loses its ability to regulate its internal environment and can hardly maintain its selective permeability for ions and molecules. As membrane damage continues, its structural stability deteriorates. Eventually, the membrane may become so compromised that it ruptures or disintegrates, ultimately leading to cell death.

b) Apoptosis: programmed cell death to combat the virus

When a cell realizes it has been hijacked, it sometimes pulls the emergency brake – sacrificing itself for the greater good: it commits suicide to stop the virus from spreading. The plan: take the enemy to the grave. Instead of dying with a bang, the cell undergoes a controlled breakdown into small fragments called apoptotic bodies, which are then cleared away by immune cells.

This process follows a precise sequence: the DNA is fragmented, the cell membrane forms characteristic bubble-like protrusions (known as blebbing), and internal structures are neatly dismantled and recycled. The cell dies quietly – and in doing so, protects the organism.

This mechanism proves – cells have more honor than some governments!

Healthy Cell: On the left, an intact cell is shown with an undamaged cell membrane and nucleus. The nucleus contains complete DNA strands, and the cell shows no signs of stress or damage.

Infected cell – initiation of apoptosis: In the middle section, the cell begins to show visible changes. The cell membrane forms bubble-like protrusions (blebbing), and the nucleus starts to shrink. Within the nucleus, fragmented DNA becomes visible, resulting from apoptotic processes. This phase marks the transition from a functioning cell to its controlled disintegration.

Apoptotic Bodies and Degradation: On the right, the cell breaks apart into several small fragments known as apoptotic bodies. In the background, an immune cell (macrophage) is shown engulfing and degrading these fragments. This process prevents the release of viral components and protects the surrounding tissue from further infection.

c) Immune response: Destruction by the immune system

Once the immune system detects a virus-infected cell, it sounds the alarm – and that spells trouble for the virus! Specialized fighters like natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells leap into action. They identify infected cells by viral protein signals that wave like warning flags on the cell surface. With deadly precision, they release toxic molecules, destroy the infected cell, and effectively slow down viral replication!

Anyone curious to learn more about this fascinating defence battle can find detailed information in „The Wonderful World of Life”, especially in Chapter 5.3 d) „Natural Killer Cells” and Chapter 5.5.7 b) „Cytotoxic T Cells”.

NK cells and cytotoxic T cells form an unbeatable team – they hunt down and eliminate viral threats, keeping the infection under control.

Regeneration of Epithelial Cells

As previously mentioned, the influenza virus primarily infects the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract – especially the cells of the nasal mucosa, the bronchi, and the alveoli (tiny air sacs) in the lungs. Due to viral replication and the immune response – particularly through natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells – many of these cells are severely damaged or destroyed.

Once the acute infection has been brought under control, the repair process begins: specialized stem cells initiate the regeneration of the tissue. They proliferate and differentiate into the various types of epithelial cells needed to restore the respiratory tract.

- Upper respiratory tract (nose, bronchi): New ciliated cells are formed, whose fine hair-like structures (cilia) transport mucus and foreign particles upward. In addition, goblet cells are generated, which produce mucus to keep the airways moist and protected.

- Lungs (alveoli): Here, the damaged, flat epithelial cells are replaced. These cells are essential for enabling the exchange of oxygen between the air and the blood.

The duration of regeneration varies depending on the severity of the infection. In the case of a mild illness, the epithelium can be completely renewed within one to two weeks. However, after more severe infections – such as influenza pneumonia – the healing process can take several weeks. Once the new cells form a dense layer, the protective function of the airways is restored. In most cases, regeneration is complete; however, in cases of very severe damage, scarring or structural changes in the epithelium may remain.

2.9. Self-Limiting Dangerous Viruses: Why They Rarely Cause Pandemics

Highly dangerous viruses that kill their host quickly limit their own spread. If a virus harms its host so rapidly that the person doesn’t have time to infect others, the chain of transmission is effectively broken. One example is the Ebola virus, which often remains locally contained and therefore rarely causes pandemics.

In contrast, viruses with moderate pathogenicity are more likely to cause global outbreaks. Moderate pathogenicity refers to a pathogen’s ability to cause disease without triggering extremely severe or fatal outcomes in most infected individuals. Such viruses typically lead to mild to moderate symptoms, allowing infected people to remain mobile and socially active. This increases the likelihood of transmitting the virus to others. Many influenza viruses are examples of this. Severe cases of influenza infection mainly occur in individuals with weakened immune systems, advanced age, or preexisting health conditions. In these cases, careful medical monitoring and intensified treatment are necessary to prevent serious complications.

The most successful viruses aren’t the ones that kill us – but those that keep us just alive enough to do their dirty work for them.

2.10. Why Does the Virus Make Some People Sick and Others Not?

💡Note: For a better understanding of this section, we recommend Chapter 5 in the treatise „The Wonderful World of Life”. It explains the fundamentals of the immune system in a clear and accessible way.

Not everyone infected with the influenza virus falls ill to the same degree: some experience only mild symptoms like a runny nose, others develop severe flu with fever and shortness of breath, and some remain completely asymptomatic. Why is that? The answer lies in a complex interaction between the virus and the host – i.e. the person who becomes infected. Several key factors play a role in this:

The host’s immune system

Every person has an individual immune system that responds differently to the influenza virus. Previous flu infections can provide partial immunity because the immune system has developed antibodies and memory cells that recognize and combat the virus more quickly. A strong immune system can suppress the infection at an early stage, whereas a weakened immune system (e.g., in older adults or chronically ill individuals) is often overwhelmed.

The viral load

The amount of viral particles entering the body during initial contact – the so-called viral load – affects the course of the infection. With a low viral load, the innate immune system can quickly recognize and eliminate the intruders before they multiply extensively. However, a high viral load, for example through close contact with an infected person, poses a greater challenge and can intensify the infection process.

10 viruses in the throat? No problem.

10,000 viruses? Straight to bed!

The host’s genetic predisposition

Two people, one virus – but only one gets sick. Some individuals carry genetic variants in their immune system that make them either more susceptible or more resistant to the influenza virus. For example, differences in genes that regulate immune receptors can affect how effectively the immune system recognizes the virus.

There are numerous studies investigating the varying immune responses caused by genetic predisposition:

The study „IFITM3: How genetics influence influenza infection demographically” showed that people with certain variants of the IFITM3 gene (Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 3) are less likely to develop severe influenza because this gene inhibits the replication of the influenza virus within cells.

The study „HLA targeting efficiency correlates with human T-cell response magnitude and with mortality from influenza A infection” investigated how HLA alleles (MHC class I) influence the T-cell response to the influenza virus. It found that certain HLA alleles present influenza peptides more efficiently and trigger a stronger T-cell response. People with these alleles experienced milder courses of influenza infections, whereas other alleles were associated with weaker T-cell responses and higher mortality. This demonstrates that genetic differences in MHC molecules can directly affect the severity of an influenza infection.

The virus’s mutant cloud

As mentioned earlier, the influenza virus does not exist as a uniform strain but rather as a „mutant cloud” – a diversity of genetic variants that arise due to the error-prone RNA polymerase. Some variants in this cloud are more aggressive because they, for example, bind better to cells or evade the immune system. Which variant dominates can determine the severity of the infection.

Tissue specificity of the virus

Influenza viruses differ in their preference for certain tissues in the body. Most strains primarily replicate in the upper respiratory tract (e.g., nose and throat), which often leads to milder symptoms such as a sore throat. Other strains penetrate deeper into the lungs and can cause severe pneumonia.

📌 Conclusion: Cheers to diversity!

The interaction between virus and human is like Tinder for microbes – some matches are harmless, others end in disaster. What really matters is:

- Host poker (genes + immune system)

- Virus roulette (dose + mutations)

- Tissue Tinder (where does the virus land?)

Our body is no passive target – it’s a learning system. Every infection is an update for the immune memory, every virus a lifelong training partner. Because only through the fight does our shield grow – for a lifetime.

3. A Look at the Beginnings of Microbiology – How It All Started

The history of microbiology is a journey from invisibility to clarity, from speculation to concrete knowledge. Its origins can be traced back to the 17th century, when human curiosity and technological innovation first unveiled a hidden world.

3.1. Early Discoveries: The First Glimpses into the Invisible

3.2. The Birth of Modern Microbiology

3.3. The Step into the World of Viruses

3.4. Viruses and Koch’s Postulates

3.1. Early Discoveries: The First Glimpses into the Invisible

In 1665, it was Robert Hooke who, using an early microscope, first described plant cells and thereby coined the term „cell”.

But the real breakthrough came a few years later with Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. Using his self-crafted, extremely powerful lenses, he was the first to observe tiny, living organisms in 1676, which he called „animalcules” – little animals like bacteria and single-celled creatures that we recognize today. Van Leeuwenhoek’s discoveries opened an entirely new perspective on nature, yet understanding how these organisms lived or caused diseases was still far from reach.

3.2. The Birth of Modern Microbiology

It took almost two centuries before microbiology was systematically studied. In the 19th century, the field experienced a quantum leap. Louis Pasteur disproved the old idea that life could spontaneously arise from nothing (the theory of spontaneous generation) and demonstrated that microorganisms are responsible for processes like fermentation and decay. His work laid the foundation for the germ theory of disease, which was later further developed by Robert Koch.

Koch’s research led to a crucial milestone in 1876: the Koch’s postulates. These rules made it possible for the first time to identify microorganisms as specific causes of diseases. Koch’s work revolutionized bacteriology and made it possible to definitively detect pathogens such as the anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis) and later the tuberculosis pathogen.

However, while microbiology made great advances in studying bacteria, viruses remained hidden for a long time. Even the best microscopes of that era were unable to visualize these tiny, invisible particles.

3.3. The Step into the World of Viruses

The end of the 19th century brought the next breakthrough. In 1892, Dmitri Ivanovsky demonstrated that a filtered extract from tobacco plants suffering from tobacco mosaic disease remained infectious, even after passing through porcelain filters that retained bacteria. Martinus Beijerinck confirmed these observations and coined the term „virus” (from the Latin word for „poison” or „slime”) for the mysterious, non-bacterial pathogen. This marked the beginning of the systematic study of this new world.

The true access to the world of viruses, however, was only made possible with the electron microscope, developed in the 1930s. It was only then that scientists could visualize viruses and understand their structure.

3.4. Viruses and Koch’s Postulates

In discussions about the detection of viruses, Koch’s postulates are often used as a benchmark to question the existence of viruses. But how do these postulates, developed in the 19th century, fit into today’s understanding of infectious diseases? A look at the historical background and scientific advancements helps to clarify this question.

Koch’s Postulates: A Scientific Milestone

Robert Koch (1843–1910), one of the founders of modern bacteriology, developed the postulates named after him to prove the connection between microorganisms and infectious diseases. They were presented in 1890 at the 10th International Medical Congress and consist of four criteria:

Postulate 1: The microorganism must be found in every case of the disease, but should not be present in healthy organisms.

Postulate 2: The microorganism must be isolated from the diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

Note: A pure culture means that only a single species of microorganisms is cultivated, without any other species mixed in.

Postulate 3: A previously healthy individual shows the same symptoms after infection with the microorganism from the pure culture as the individual from whom the microorganism originally came.

Postulate 4: The microorganism must be re-isolated from the experimental host and identified as the same one.

These groundbreaking principles laid the foundation for experimental medicine and the germ theory of disease.

Robert Koch: A Pioneer Against Resistance

Robert Koch studied the pathogens of diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax. For his research, he often traveled to epidemic regions, such as Calcutta to study cholera or Bombay during the bubonic plague. Koch spent months in these countries, always close to the epicenter of the outbreaks. In his laboratory tent, he worked tirelessly at the microscope.

However, Koch faced significant resistance. At his time, the idea that diseases were caused by microscopic organisms was still controversial. Many of his colleagues and contemporaries were skeptical and rejected his theories. Scientists often believed back then that plagues and epidemics were caused by so-called miasmas – toxic vapors rising from the ground.

Despite these challenges, Koch tirelessly pursued his research. He utilized innovative techniques of his time, such as the agar plate and oil immersion lenses, to cultivate and study bacteria. These methods enabled him to make important discoveries and revolutionize the understanding of infectious diseases.

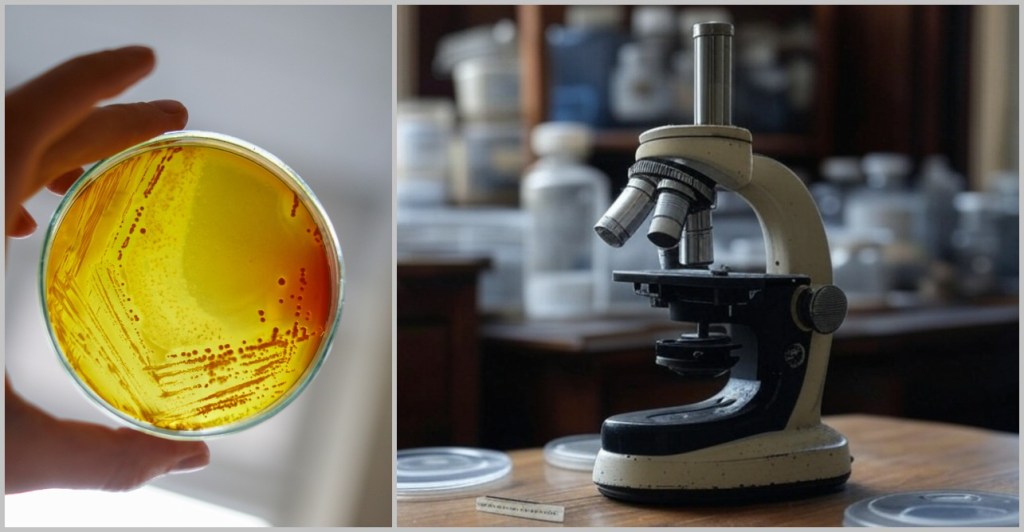

Left: An agar plate – a solid nutrient medium in a petri dish, with agar added as a gelling agent to selectively cultivate bacteria. Right: A microscope with an oil immersion lens – a special microscopy technique where a drop of oil is placed between the objective lens and the specimen to minimize light refraction, making the tiniest microbes appear sharper.

Challenges and Limitations of the Postulates

It was precisely the skepticism directed against his theories that prompted Koch to formulate the postulates in order to provide proof of a connection between the pathogenic properties of bacteria and the disease.

Koch himself recognized that his postulates do not always apply universally. A well-known example is his work with the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. He discovered that this microorganism can be present not only in sick individuals but also in apparently healthy people. This finding challenged the first postulate and led Koch to abandon the universal validity of this criterion.

Koch’s Spirit of Innovation

Koch was a pioneer of his time. In his speech at the 10th International Medical Congress, he stated:

„It was necessary to provide irrefutable evidence that the microorganisms found in an infectious disease are truly the cause of that disease.”

His scientific approach of convincing skeptics through strict evidence was groundbreaking. Yet, he himself recognized that new technologies and methods were needed to answer further questions:

„With the experimental and optical aids available, no further progress could be made and it would probably have remained so for some time if new research methods had not presented themselves at that time, which suddenly brought about completely different conditions and opened the way to further penetration into the dark area, with the help of improved lens systems …”

Regarding hard-to-detect pathogens such as those causing influenza or yellow fever, he remarked:

„I tend to agree with the view that the diseases mentioned are not caused by bacteria at all, but by organized pathogens that belong to entirely different groups of microorganisms.”

Koch was already on the trail of viruses but was unable to definitively identify them due to the limited technical capabilities of his time. However, he recognized that these invisible pathogens must exist.

Why viruses break Koch’s postulates?

Koch’s research results corresponded to the scientific knowledge of his time. In the 19th century, microbiology was still in an early stage of development, where fundamental principles were just being discovered and systematically studied. Virology as an independent field emerged only after Koch’s era, when Dmitri Ivanovsky and Martinus Beijerinck discovered infectious particles smaller than bacteria. With the invention of the electron microscope in the 1930s, viruses could finally be visualized. However, viruses differ fundamentally from bacteria, which is why Koch’s postulates are often not directly applicable to them:

➤ Host dependence: Viruses can only replicate inside living host cells and cannot be grown in pure culture.

➤ Asymptomatic infections: Many viral infections occur without symptoms, making it difficult to clearly associate the pathogen with the disease.

➤ Complex detection methods: Modern molecular techniques such as PCR allow for the detection of viral genome sequences, requiring an extension of the classical postulates.

Koch and Modern Science

Robert Koch and his contemporaries laid the foundation for microbiology, particularly through the development of methods for isolating and cultivating bacteria. The germ theory of disease was a milestone in the history of science at the time. Koch understood that science is constantly evolving. If Koch had had access to modern technologies such as PCR, sequencing or electron microscopes, would he have adapted his methodology?

Modern technologies such as PCR and sequencing will be introduced in the following chapters.

His closing words at the 1890 congress provide the answer and reflect his optimism for the future:

„Let me conclude with the hope that the nations may measure their strength in this field of work and in the war against the smallest but most dangerous enemies of mankind, and that in this struggle, for the benefit of all humanity, one nation may continually surpass another in its achievements.”

If Robert Koch had been able to witness today’s advances in molecular biology, virology, and immunology, he would likely have been fascinated – not only by the new insights, but also by the revolutionary methods that make it possible to visualize even the tiniest pathogens. After all, this was precisely his motivation: to make the invisible visible, to decipher what is hidden. How might he have reacted to the first images of a virus under an electron microscope?

From the First Observations to Modern Science

What once began with dusty lenses and puzzled gazes has now become high-tech down to the molecular level. With every new technology, we peer deeper into the microcosm. Microbiology has made the invisible visible – but only modern technology allows us to truly understand the invisible. Today, we track viruses that evaded our sight for centuries.

And how we uncover the invisible today – that is the story of the next chapter.

4. Modern Methods for the Discovery and Analysis of Viruses

So far, we have familiarized ourselves with the topic of viruses. In this chapter, we shift our perspective: from wonder to measurement. Without the methods of modern biology, we would know little about viruses – their structures, their genetic material, their diversity.

What follows is a look into the engine room of science. Admittedly, a technical section – but an important one: because it is here that we see how we are able to grasp the invisible at all.

Anyone eager to understand how viruses are made visible, decoded, catalogued, and analyzed today will find here a kind of 21st-century toolbox.

But when and why do we turn to these tools?

The identification of viruses can serve different purposes: some viruses come into focus because of their impact on humans, animals, or plants, while others are discovered in environmental samples or unexplored habitats to better understand their ecological significance. The detection of known viruses is primarily used for diagnostics, whereas the identification of unknown viruses offers insights into biological diversity and evolution.

Since viruses lack universal features such as a shared cell structure, detection methods focus on their genetic material, their structure, or their interactions with host cells. The detection process does not follow a rigid scheme but instead combines various steps that vary depending on the research question and the type of virus.

The following sections will provide a detailed explanation of the key methods used for virus identification – from sample collection to bioinformatic analysis.

Procedures for the identification of viruses

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. Sample Preparation

4.2. a) Filtration

4.2. b) Centrifugation

4.2. c) Precipitation

4.2. d) Chromatography

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Making Viruses Visible

4.4. a) Electron Microscopy

4.4. b) Crystallization

4.4. c) Cryo-Electron Microscopy

4.4. d) Cryo-Electron Tomography

4.4. e) Summary

4.5. The Genetic Fingerprint of Viruses

4.5.1. Nucleic Acid Extraction

4.5.2. Nucleic Acid Amplification

4.5.3. Sequencing

4.5.3. a) First Generation: Sanger Sequencing

4.5.3. b) Second Generation: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

4.5.3. c) Third Generation: New Approaches in DNA Sequencing

4.5.3. d) Emerging Technologies: The Future of Sequencing

4.6. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.1. Sample Collection

Before we can track down viruses, we first have to find them – and that’s like a micro-scale treasure hunt, with hiding places ranging from blood to deep-sea sediment. Whether in humans, plants, or the ocean, viruses are everywhere, and researchers become detectives equipped with pipettes, protective suits, and specialized gear.

A) from humans, B) from soil, C) from marine ecosystems [Tara Oceans-Mission]

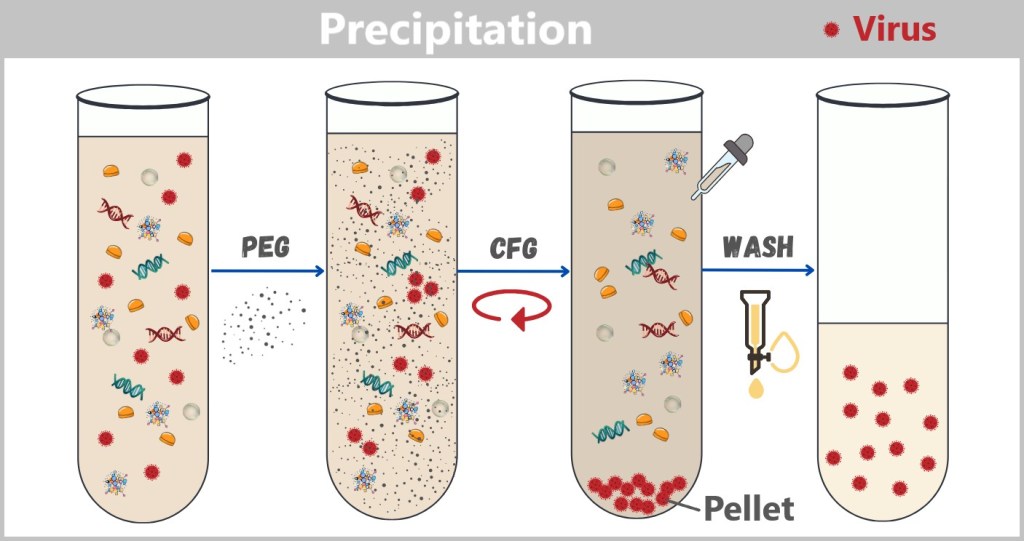

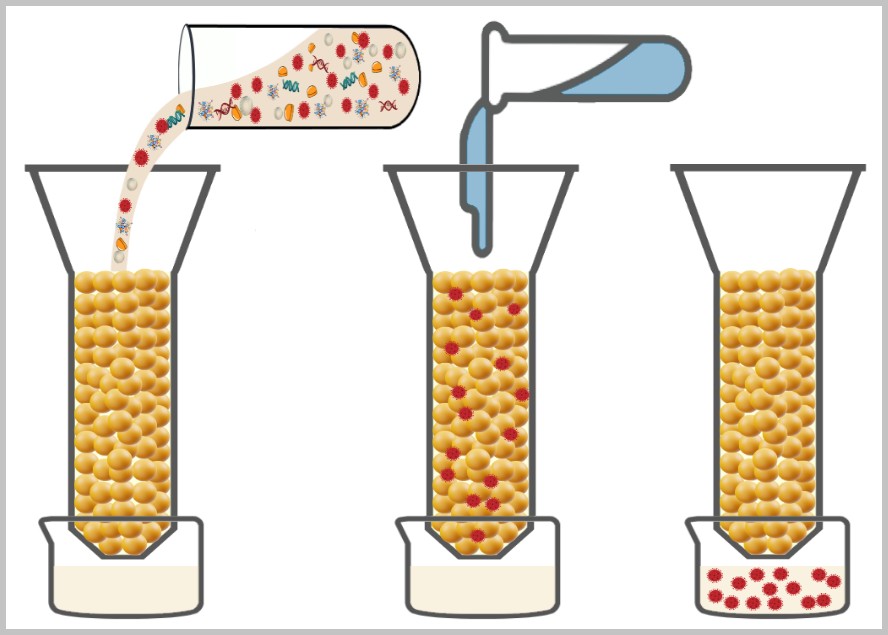

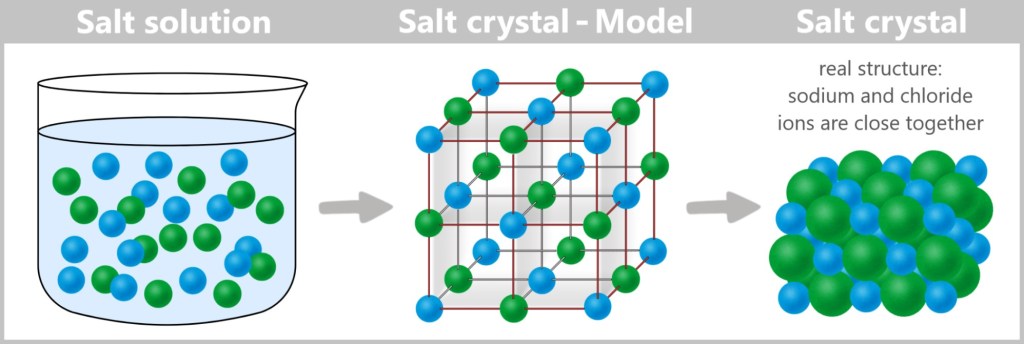

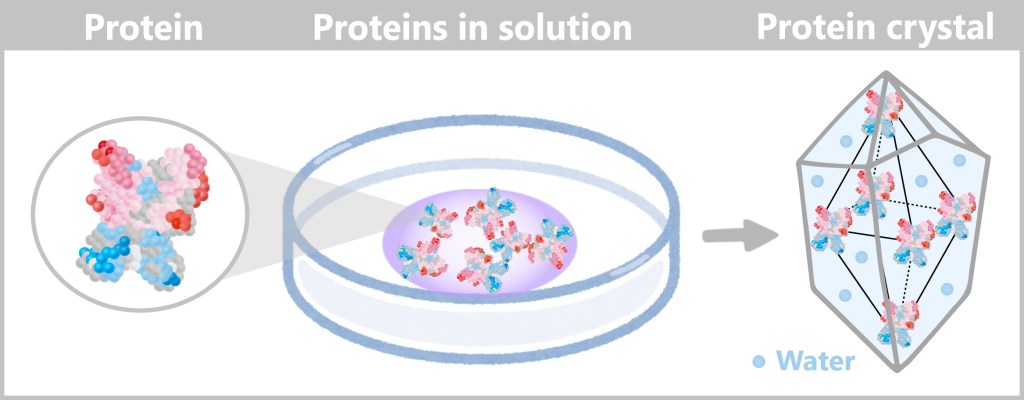

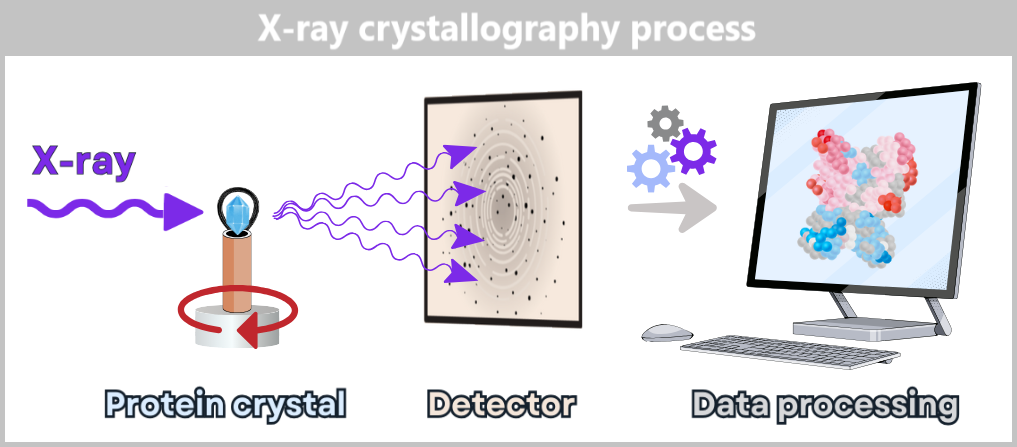

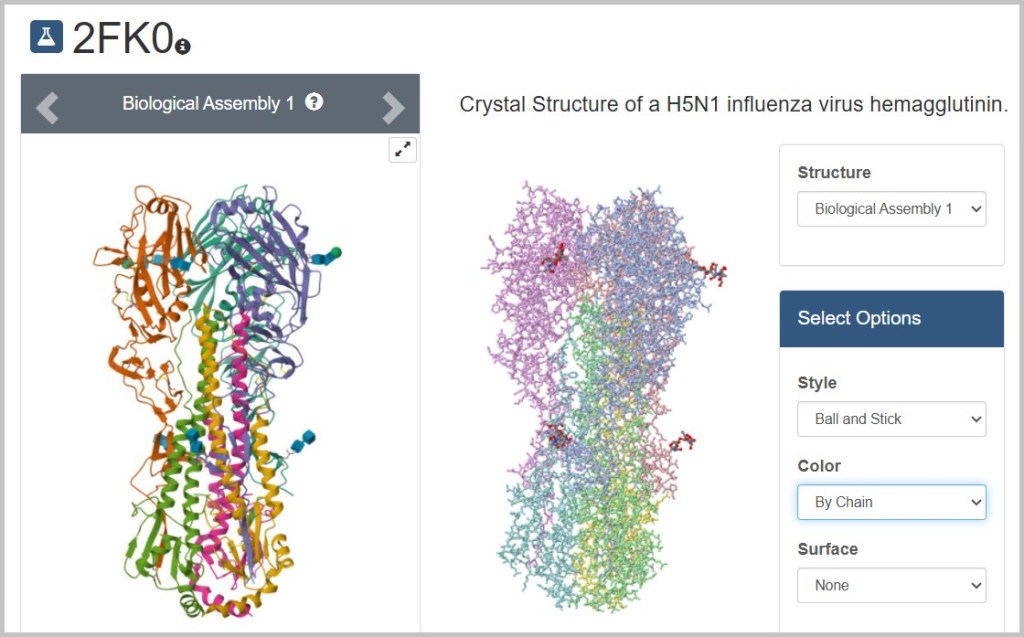

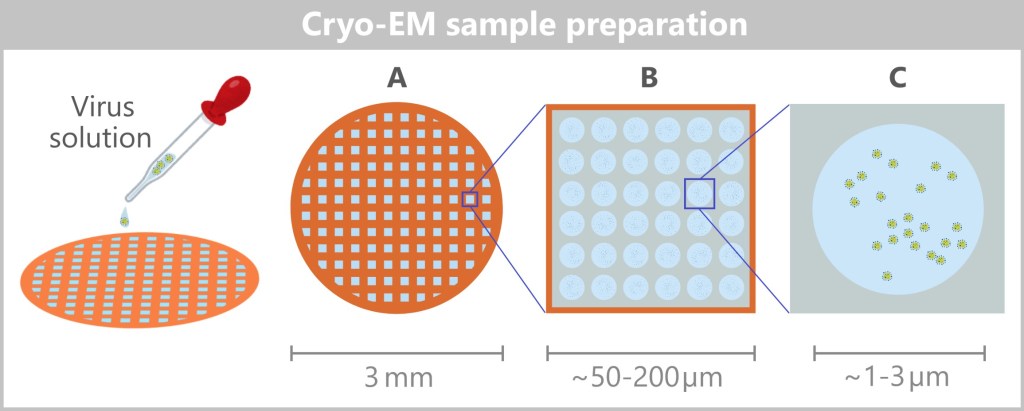

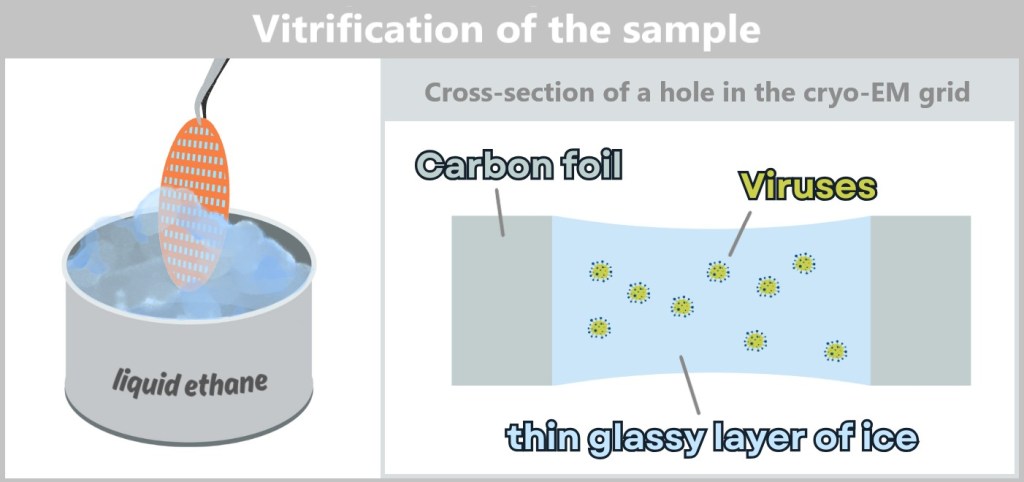

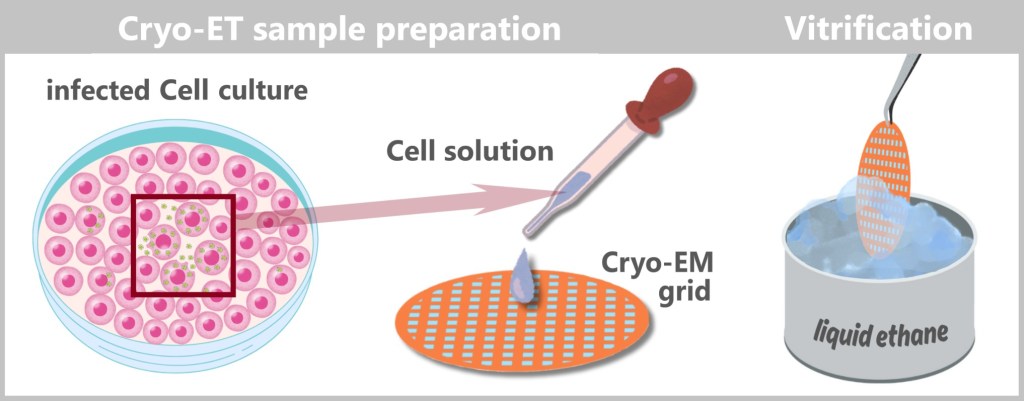

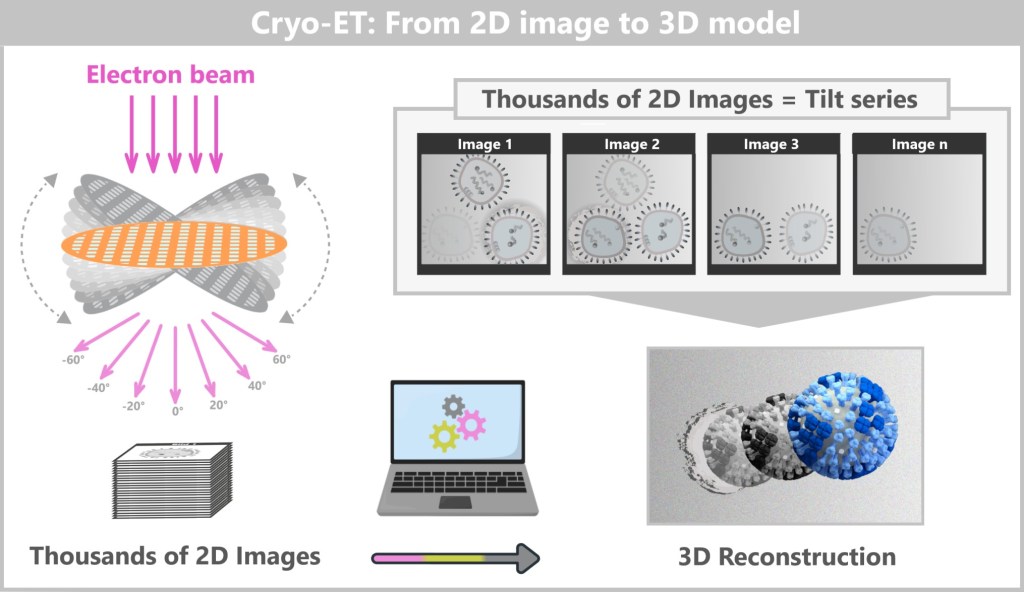

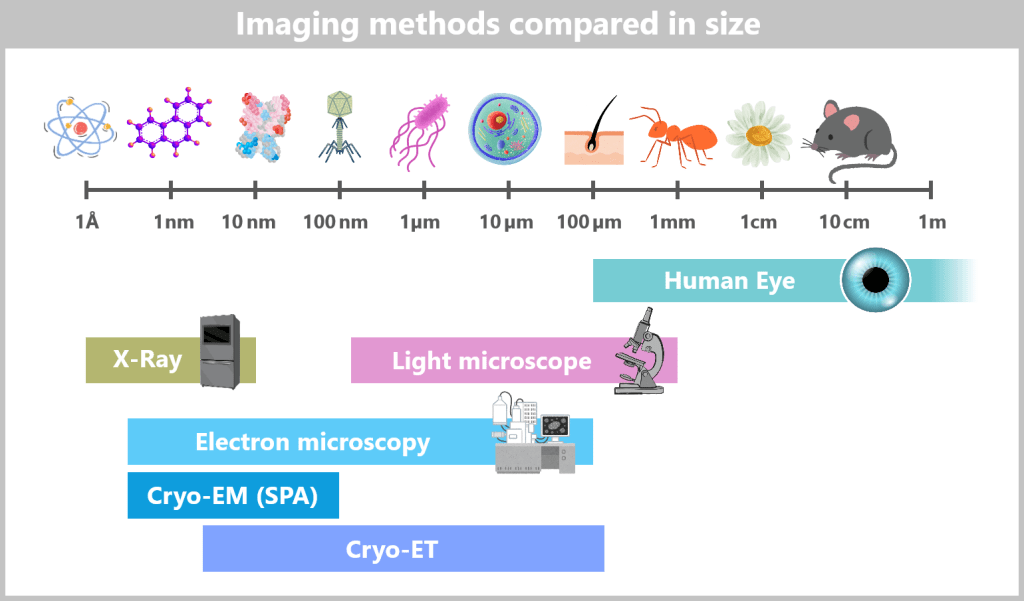

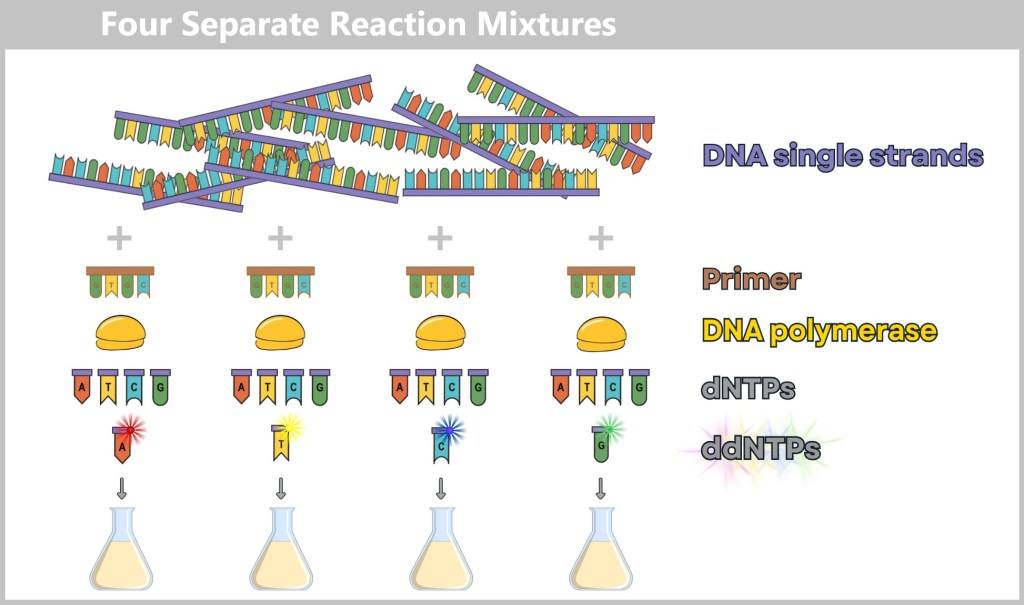

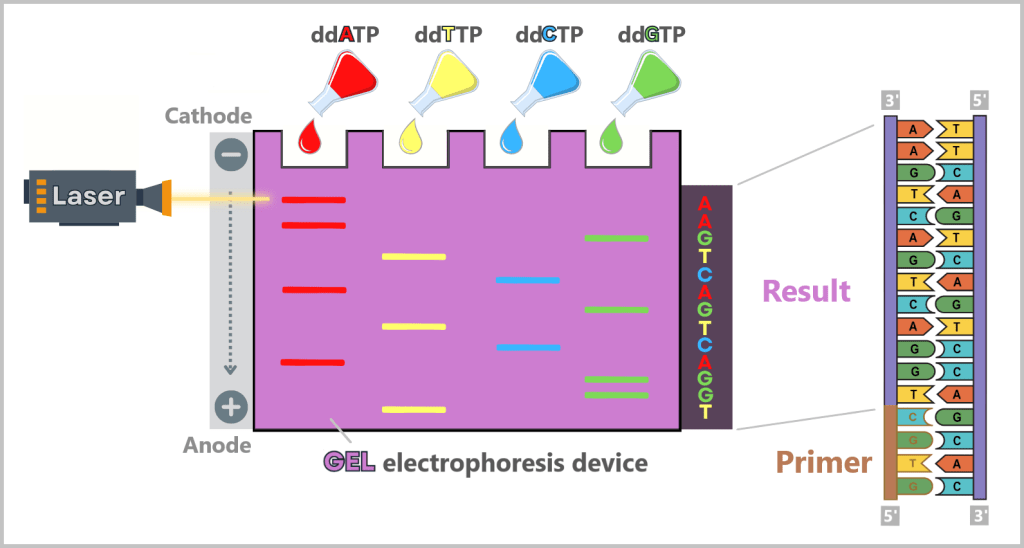

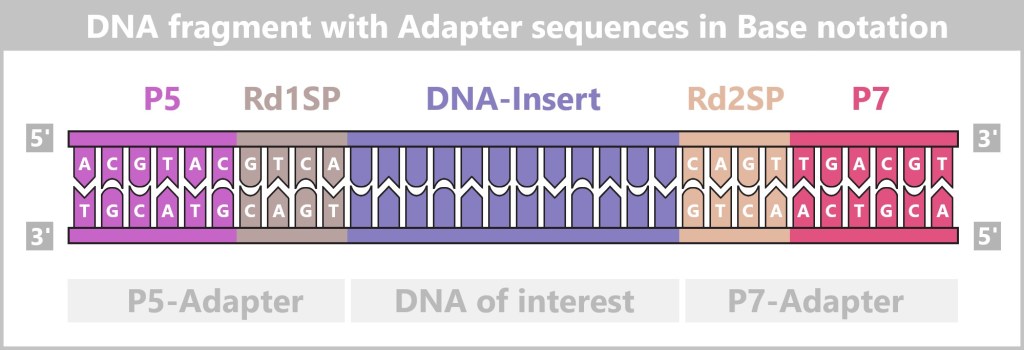

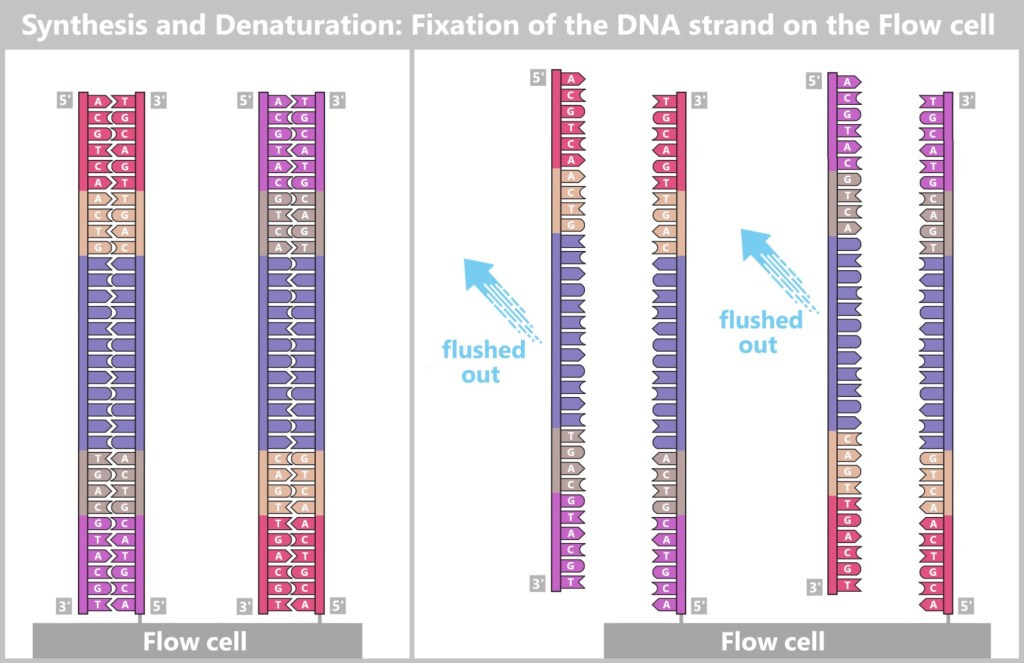

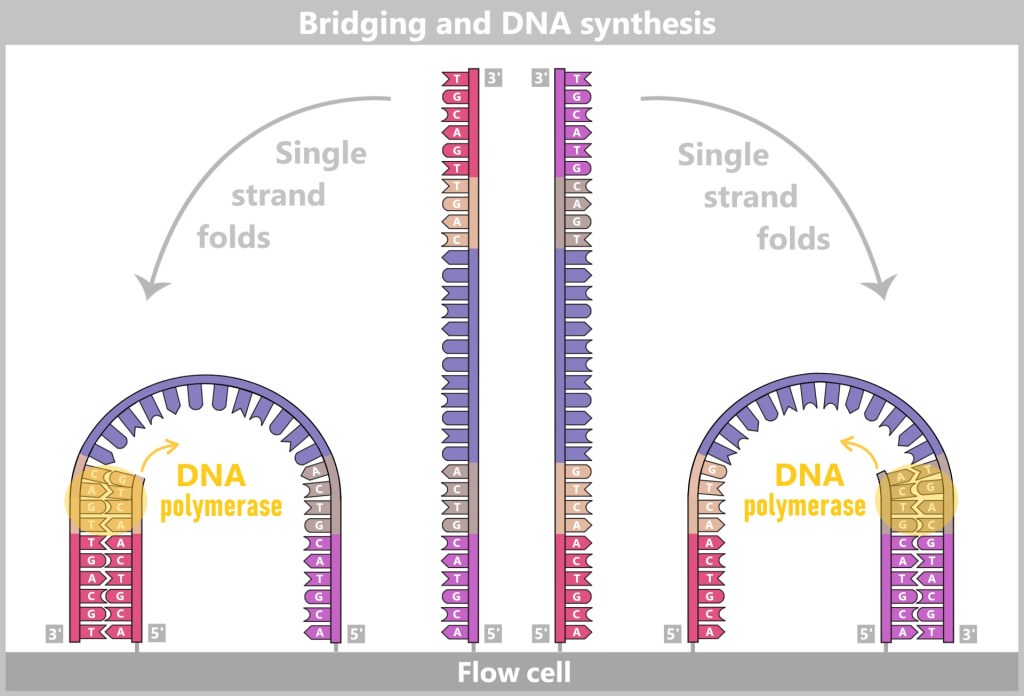

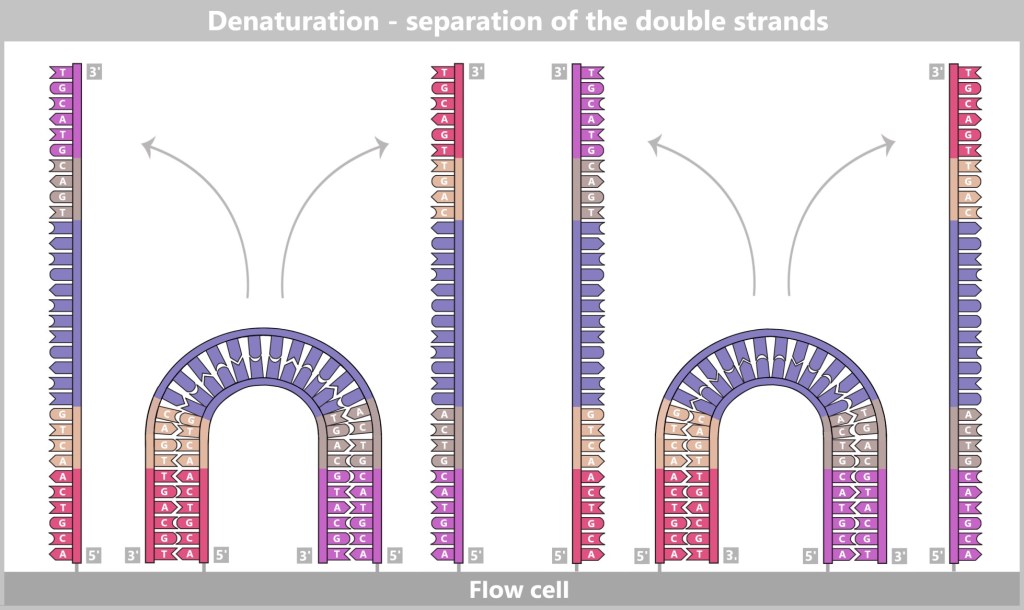

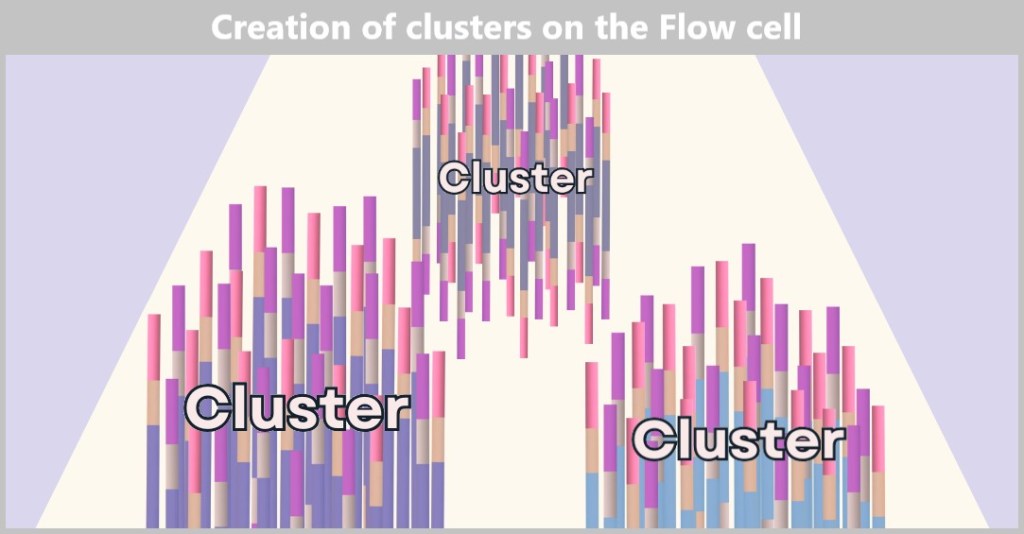

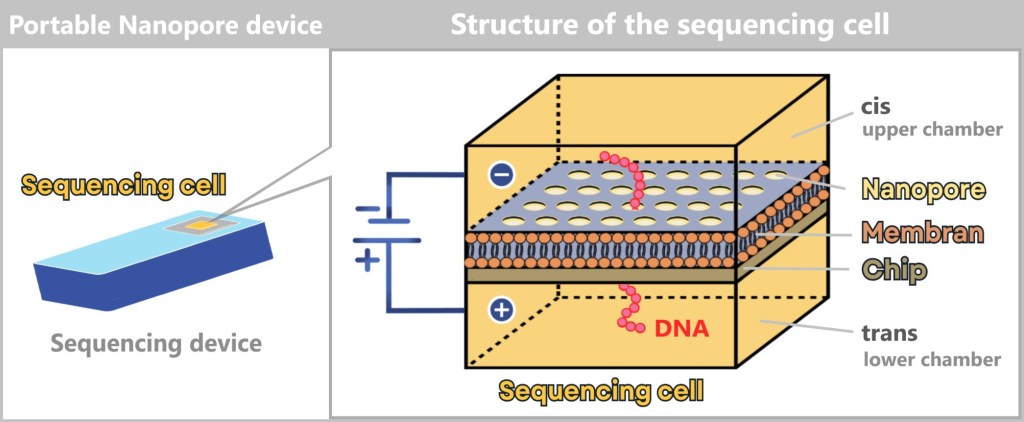

Human Samples