When we look at life – from deep forests to snow-covered peaks, from shimmering coral reefs to mighty blue whales, from tiny microbes to buzzing insects – we see a story that has unfolded over billions of years. This story is often described as the „Tree of Life”: a web of branches that connects all species and leads back to a common origin.

But the deeper we look into this tree, the more blurred its roots become. They fade into the mist of time – and there, at the very beginning of everything, another story whispers: a hidden, mysterious tale.

It began in the half-light. In the warm veins of the earth, where bubbling springs washed around elements and the green sea was still an alphabet of ions. Between clouds of sulphur and black basalt, the first words folded themselves out of molecules, fragile at first, entangled in the thermal breath of the depths. Not life, not death – just a hunch. Molecules that carried information and drove chemical reactions. Sometimes they broke apart. Sometimes they probed one another. And sometimes, very quietly, they kept whispering.

Was this whisper a coincidence? Or already a plan?

Anyone who sets out to discover the origin of life does not enter a well-lit museum – but a labyrinth. There is no clear „this is how it was”, but rather a web of hypotheses, probabilities, mechanisms and gaps. What we know today about the beginnings of life is the result of intensive research, astonishing discoveries – and always: unanswered questions.

In this labyrinth, many paths lead into the unknown. One of the most fascinating trails is the RNA world hypothesis: a narrative in which tiny molecules – RNA – sang the first notes of life. But other stories whisper along: of minerals that held molecules together, of tiny protein chains that created stability, of fat-like shells that provided protection. Perhaps all these paths were intertwined – and yet together they led to RNA, which built a bridge between chemistry and life. To where the first whisper became audible.

This text follows the trail through the mist:

the idea that RNA was once the beginning of it all.

Act 1: From Chaos to the RNA World – The Building Blocks Awaken

Scene 1: Primordial Soup – The Birth of Simple Molecules

Scene 2: Bases – Letters of Nitrogen and Carbon

Scene 3: Sugar: Ribose – Sweet and Fragile

Scene 4: Phosphate – The Universal Glue

Scene 5: Stardust & Impacts – A Cosmic Contribution?

Act 2: Nature’s Laboratories – Birthplaces of RNA

Scene 1: The Forge of the Deep – Hydrothermal Vents

Scene 2: The Alchemy of Clay – Birthplaces on Land

Scene 3: Many Paths, One Goal

Act 3: The First Self-Replicators Awaken

Scene 1: From Chain to Tool – RNA’s Functional Maturation

Scene 2: The Power of Folding

Scene 3: The Energetic Pact

Scene 4: Partial Replication

Scene 5: Separation – A Farewell That Created Something New

Scene 6: From Short to Longer Chains – The Power of Ribozymes

Scene 7: Errors as Opportunity – The Engine of Evolution

Act 4: Life in a Droplet – Lipid Vesicles as Shelters

Scene 1: The First Strongholds

Scene 2: The Entry – Carryover or Immigration?

Scene 3: The Pact – RNA Stabilizes, Vesicles Protect

Scene 4: The Chance of Imperfection

Scene 5: Selection Within the Droplet

Act 5: From Chance to Function – How RNA Gained Complexity

Scene 1: A Random RNA Emerges

Scene 2: From RNA Strand to Ribozyme

Scene 3: RNA Copies Itself – With Errors

Scene 4: Mutation Creates a New Function

Scene 5: Selection Favors Useful RNAs

Scene 6: RNA Between Error and Function

Epilogue: The Echo of the Primordial Soup

Act 1: From Chaos to the RNA World – The Building Blocks Awaken

Today, life is a well-organized structure: DNA archives knowledge, RNA transmits messages, proteins do the work. But in the beginning, there was no structure – just a single molecule – that could do everything: RNA. It could have been the first actor – simultaneously archive, messenger and tool.

This is precisely what the RNA world hypothesis proposes: RNA as the first „building block of life”, capable – like DNA – of storing information, and – like enzymes – of catalyzing chemical reactions, all on its own and without assistance.

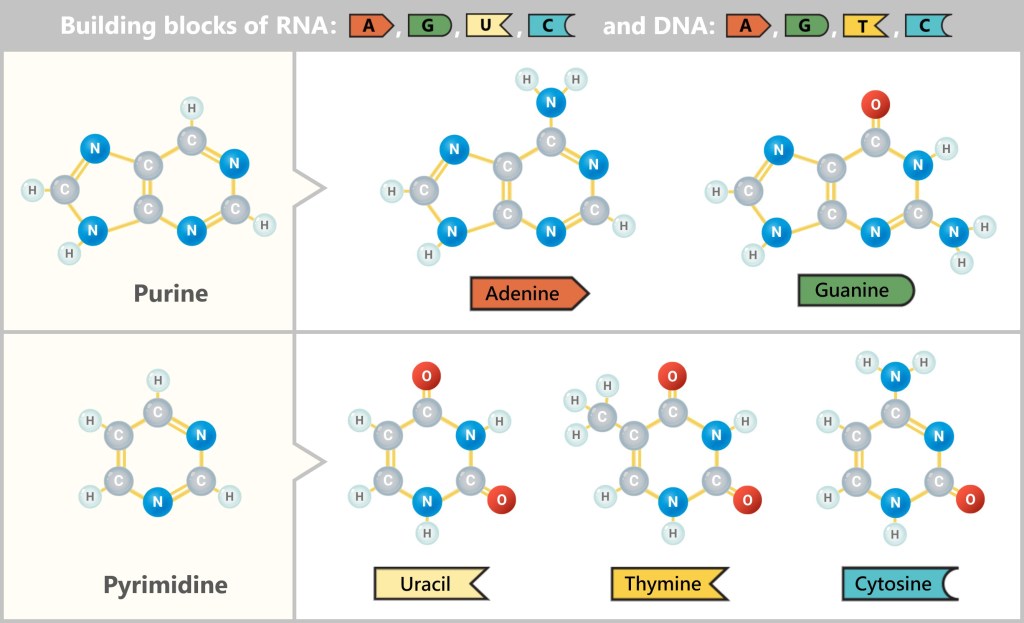

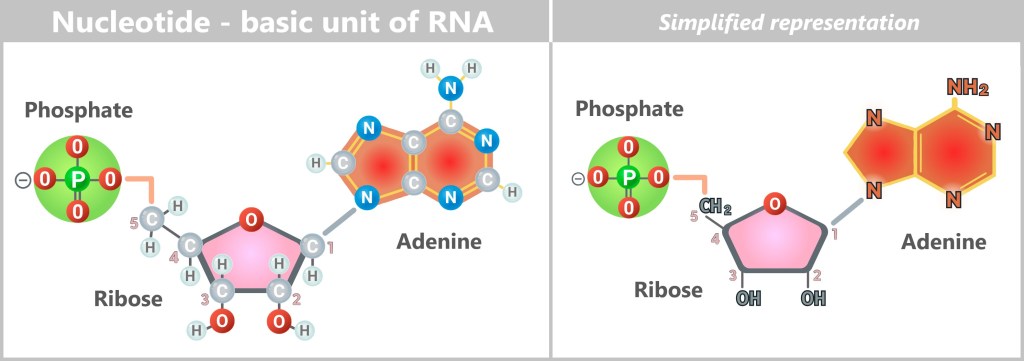

RNA is made up of repeating building blocks – nucleotides.

Each nucleotide consists of three parts:

🧩 a nitrogenous base (such as adenine, uracil, guanine, or cytosine),

⬟ a sugar (ribose), and

⚡ a phosphate group, which acts like a bracket and joins the units together to form a chain.

But how did this miracle molecule come into being in a lifeless world?

Scene 1: Primordial Soup – The Birth of Simple Molecules

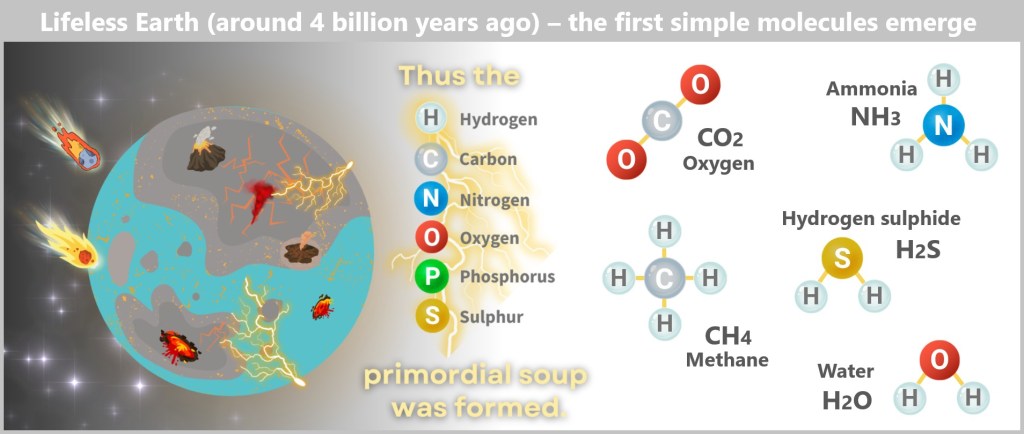

Around four billion years ago, the worst birth pangs of the young Earth had passed – but the planet remained a fiery, restless chaos. Volcanoes spewed toxic gases and bubbling lava, meteorites carved crater-like wounds into the surface, and the young oceans boiled from the impacts.

Here, in this glowing wilderness, six elements mixed to form a primordial cocktail:

- Hydrogen – as fleeting as a ghost’s breath

- Carbon – the supple connector

- Nitrogen – stubborn, yet essential

- Oxygen – fiery and highly reactive

- Phosphorus – the energy-rich spark

- Sulphur – smelly, but incredibly useful.

These basic elements were omnipresent – deep within the Earth’s rock, dissolved in the hot seas or released by volcanic embers. They were just waiting for energy. Lightning flashed through the haze, UV light blazed on the tidal zones, and deep below, magma baked the oceans into chemical cauldrons. Gradually, the elements combined into gases like methane (CH₄), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and ammonia (NH₃) – simple molecules, yet rich in chemical potential.

And they kept reacting. In hot oceans, on drying mudflats, or in mineral-rich springs, these gases formed organic molecules like hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and formaldehyde (CH₂O) – deadly substances that, paradoxically, became the raw materials that made life possible.

Could the building blocks of life really have formed in this hellish landscape?

In 1953, two researchers provided the answer – in a glass jar barely bigger than a teapot. Stanley Miller and Harold Urey mixed methane, ammonia, hydrogen and water vapor – and let lightning flash through it.

After a week, the liquid – the „primordial soup” – had turned cloudy with amino acids: those organic compounds that would later give rise to proteins, the „molecular machines of cells”. Not yet life, but proof: out of chaos, order can emerge.

And then the discovery that was hardly noticed: Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and formaldehyde (CH₂O) – two substances without which RNA would never have been created.

Today we know: the gases used in the original experiment likely didn’t exactly match the conditions of early Earth. Methane and ammonia were probably less common than once assumed, and the atmosphere was more neutral – rich in CO₂ and nitrogen. But the principle remains valid: even under simple conditions, the building blocks of life can emerge. Modern experiments (Cleaves et al., 2008; Bonfio et al., 2018) show that even in CO₂-rich environments – likely characteristic of early Earth – life’s precursors can form. With the help of minerals (Erastova et al., 2017), the synthesis becomes even more efficient.

What’s fascinating about this: there doesn’t seem to be just one path that leads to life – but many. Different environments, various reaction pathways, and diverse ingredients – and yet, time and again, the same fundamental building blocks emerge.

Even if the early Earth’s atmosphere was likely not as rich in methane and ammonia as Miller and Urey once assumed, hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and formaldehyde (CH₂O) could still have formed. Local chemical niches, lightning, UV radiation, or even meteorites repeatedly supplied energy – enough to produce these highly reactive molecules.

But how do gas and energy become a code?

The true miracle was yet to come:

Scene 2: Bases – Letters of Nitrogen and Carbon

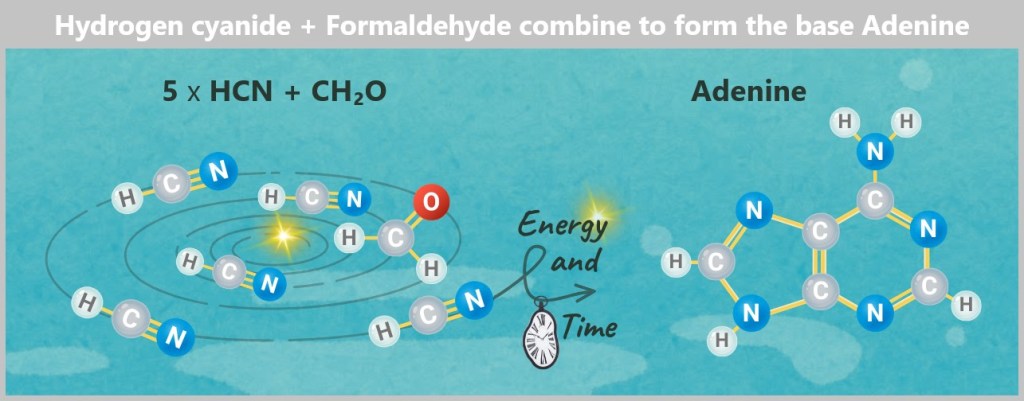

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and formaldehyde (CH₂O) were abundant in the primordial soup. In the forges of the deep – heated by volcanoes and kneaded by minerals – they combined to form purine and pyrimidine rings: organic frameworks made of carbon and nitrogen atoms.

These rings eventually gave rise to stable structures – chemical letters with astonishing permanence. Adenine was just one of them.

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) molecules encountered formaldehyde (CH₂O) in a lagoon. They reacted – not on purpose, but because chemistry demanded it. Nitrogen atoms got stuck together, carbon rings closed. At some point it was there: Adenine, the purine base that would later carry the code for entire ecosystems.

An entire alphabet of life grew from purine and pyrimidine rings: adenine and guanine from the purines, cytosine, uracil and thymine from the pyrimidines.

They were still silent, not yet carrying any message. But within their rings lay a strange potential – as if they could hold secrets they themselves did not understand.

Today we know: these reactions are part of a chemical pathway (Patel et al., 2015) that can realistically lead to the formation of purines and pyrimidines – the „letters” of RNA.

But an alphabet is not yet a word. What was still missing was a rhythm, a backbone – a structure the letters could cling to: ribose, the sweet bearer of meaning.

Scene 3: Sugar: Ribose – Sweet and Fragile

While the bases were forming in bubbling pools, Earth was weaving their delicate partner elsewhere: ribose, a sugar made of five carbon atoms – lined up like pearls on a string.

Ribose was a creature of fragile beauty:

- Sweet in its chemical soul, like all sugars, and

- Fragile, for in water it easily fell apart.

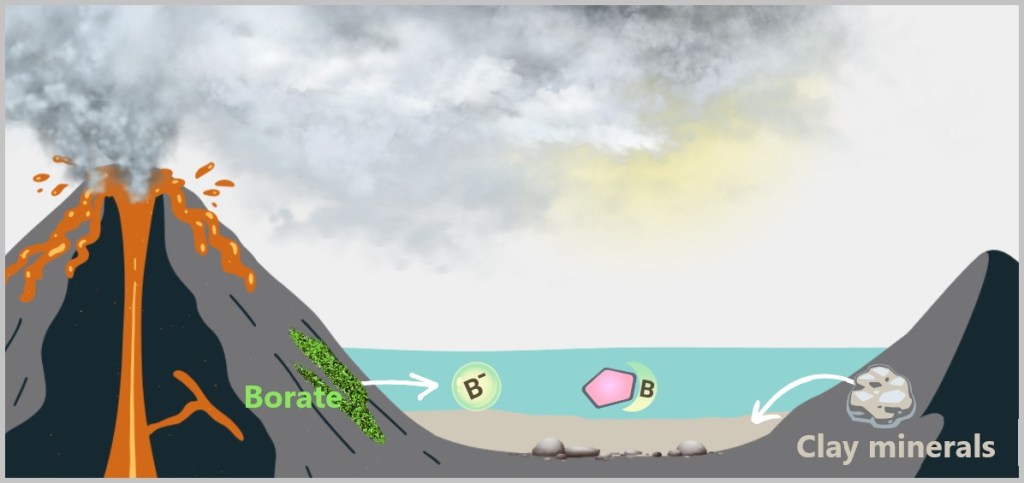

To preserve this precious molecule, the Earth reached out its arms: borate minerals from volcanic depths gently enclosed the ribose – protectively, not too tightly, and only for as long as needed. Until the right moment came to let go.

What might have happened?

In volcanic regions – especially in drying ponds or mineral–rich waters – three crucial ingredients came together:

- Formaldehyde (CH₂O), a simple organic building block,

- Energy such as UV light or volcanic heat and

- Borate minerals, formed through rock weathering.

This mixture set a chemical chain reaction in motion: the formose reaction. Several molecules of formaldehyde combined to form various sugars – one of which was ribose.

But it was just one among many – and particularly unstable. Its numerous –OH groups made it highly reactive and prone to breakdown in aqueous environments.

Salvation came from the rock: in ponds rich with borate minerals, borate ions (B(OH)₄⁻) dissolved into the water and bonded preferentially with ribose. This binding – at two neighboring –OH groups – blocked the molecule’s most vulnerable reaction sites and stabilized it. Not permanently, but long enough. Ribose could now survive not just for minutes, but for days.

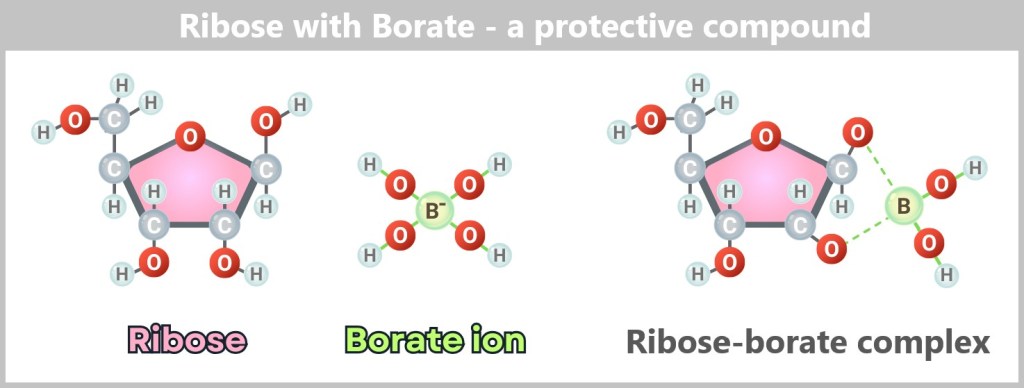

Left: Free ribose – a sugar with multiple hydroxyl groups (–OH), making it prone to degradation.

Center: Borate ion (B(OH)₄⁻) – found, for example, in borax minerals.

Right: Ribose–borate complex – the borate ion binds to two neighboring OH groups of the ribose. This „freezes“ the unstable sugar structure and protects it from decay.

Surprisingly, it was borate – a seemingly unremarkable byproduct of volcanic processes – that became the guardian of a key molecule of life.

Laboratory experiments confirm: Ribose can form in volcanic ponds – but only borate turned this chemical lottery into a viable survival strategy.

Albert Eschenmoser (ETH Zurich) demonstrated that formaldehyde, in an alkaline solution (pH 10–12, simulating volcanic ponds), polymerizes under heat into sugars like ribose – but in a chaotic fashion, yielding less than 1% ribose (Eschenmoser, 2007).

Steve Benner (Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution) demonstrated that borate ions stabilize the sugar ribose in aqueous solution – by specifically binding to certain regions of the ribose called cis-diol groups (two neighboring OH groups), thereby protecting it from degradation (Ricardo et al., 2004).

Deoxyribose – The Silent Twin

Alongside ribose, a second form quietly emerged: deoxyribose, its silent twin. Born in the same molecular dance, likely sheltered by borate, perhaps shaped by clay. Only a tiny detail set her apart from her sister: one oxygen atom was missing – hence her name: „deoxy” – without oxygen.

A seemingly small difference with immense consequences. The missing –OH group made deoxyribose less reactive, but significantly more stable. For now, she remained in the shadows – inconspicuous, unnoticed.

While ribose forms the backbone of RNA (RNA = ribonucleic acid), deoxyribose shapes the structure of DNA (DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid). Nature had made provisions: ribose for the moment. Deoxyribose for eternity.

But before the story could continue, one crucial element was still missing: a molecular glue that could link the letters to the sugars and form syllables. Nature needed a universal ally – it needed phosphate.

Scene 4: Phosphate – The Universal Glue

While ribose and the bases slumbered in the warm ponds of the young Earth, the third member of the group was still missing – a molecule that could do more than merely exist. A connector.

Phosphate was a child of fire and water: born in apatite rocks deep inside the earth, where heat and pressure melted the elements. There it remained, locked away – until the surface began to bubble.

Volcanoes spewed their fiery gases – carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide – which mixed with water to form acidic mists that broke down even the hardest rocks. Evaporation and condensation washed the phosphate from the stone into shallow pools, where sugars and bases were already drifting. There it waited – seemingly unremarkable: an ion with three negative charges, restless and ready to bind.

Phosphate was everywhere – and it could do almost anything. It was the spark that set molecules in motion, built bridges, and drove reactions. It’s no coincidence that phosphate remained the energy currency of life – the universal fuel of every cell.

But back then, it was still single.

The Great Union

It was not easy for the wild phosphate character to find a partner. It flirted with Ribose, but she was rather unstable or too passive due to her borate protector. And the bases preferred to react with themselves. Magnesium ions caressed the negative charge – they softened phosphate’s irritability and allowed a gentler approach. Evaporating water pressed the molecules together.

Phosphate finally found a foothold: it clasped ribose at the fifth carbon – a stable grip that made new reactions possible. Attracted by the molecular wrestling, a base approached. Determined, it grabbed the first carbon atom of the ribose and swung itself towards it. A twitch, a bond…

Three became one: the first complete nucleotide – the fundamental unit of RNA.

A nucleotide consists of three building blocks: a phosphate residue (green), a sugar called ribose (pink) and a nitrogenous base (here: adenine, red). The sugar has five carbon atoms (numbered 1′ to 5′). The base is bound to the 1′ carbon, the phosphate to the 5′ carbon.

The ribose is linked to the base and the phosphate by a condensation reaction with elimination of water (H2O). This forms an „N-glycosidic bond” (base-ribose, blue-grey) and a „phosphoester bond” (ribose-phosphate, orange).

Geometry, chemistry – and a touch of chance forged the triad of ribose, base, and phosphate into a single molecule. A tiny triumph, yet one that opened the door to life.

Laboratory experiments simulated primeval conditions: They showed that under the right circumstances – such as in mineral-rich, heated waters – purine and pyrimidine bases, ribose, and even complete nucleotides can form abiotically. These studies used aqueous solutions, volcanic heat, phosphate as a catalyst, and drying cycles. Their experiments demonstrated that the chemical pathways leading to these molecules were not only possible, but likely under the conditions of early Earth. (Powner et al., 2009 and Becker et al., 2016)

While the first compounds were forming in the pools, the sky looked down – and intervened. Meteor showers crashed onto the Earth. They brought new elements, new impulses. Perhaps even new ideas – in the form of molecules…

Scene 5: Stardust & Impacts – A Cosmic Contribution?

Interestingly, the building blocks of RNA may not have originated solely on Earth. In meteorites like the famous Murchison meteorite, nucleobases such as uracil and cytosine have been detected. (Callahan et al., 2011). Ribose, amino acids, fatty acids, and precursors of lipids have also been found in these extraterrestrial rock fragments (Pizzarello et al., 2006). All of this suggests that the ingredients of the RNA world may have once come from space – a cosmic gift to the young Earth.

Meteorites: The Universe’s First Life Delivery Service

These celestial messengers originated from the primordial cloud that also gave birth to our Sun 4.6 billion years ago. In the cold, dark regions of the early solar system – within molecular clouds, on comets, and on asteroids – UV light and cosmic radiation transformed simple molecules like methane and ammonia into more complex organic compounds (Bernstein et al., 2002).

During the so-called Late Heavy Bombardment, around 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago, countless meteorites hit the Earth. Amino acids, sugars and other organic molecules rained down on our planet with them – the raw materials of life, packaged as special cosmic deliveries. Comets such as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, explored by the Rosetta space probe, also delivered building blocks such as glycine and lipid precursors (Altwegg et al., 2016). Even microscopic fine dust – so-called stardust – still delivers thousands of tons of organic molecules to Earth every year. (Maurette et al., 2000).

Nucleobases such as adenine, guanine, uracil, and cytosine, as well as ribose – the fundamental building blocks of RNA. Precursors of lipids, phosphorus compounds, and glycine (the simplest amino acid) were also part of the cosmic cargo. Hydrogen cyanide (HCN), a key precursor of organic compounds, may have triggered chemical evolution. These molecules, born in the hearts of dying stars, rained down and enriched the primordial soup – a cosmic contribution to the first whisper of life.

Molecules from the depths of space for the primordial soup

Once they landed on Earth, these molecules could interact with terrestrial substances – and perhaps fuel chemical evolution. The impacts themselves provided energy: heat, pressure, and shockwaves that linked molecules and formed new structures – perhaps even the first nucleotides.

The robustness of these molecules is astonishing: they survived millions of years in space, the red-hot entry into the volcanic primeval atmosphere, the heat on impact and the harsh conditions of prehistoric times.

This cosmic contribution nourishes the so-called panspermia hypothesis, which suggests that the building blocks of life may have originated in space. While the idea that fully formed life reached Earth remains controversial, the discovery of organic molecules in meteorites supports the concept of „soft” panspermia: Earth was gifted with the ingredients of life – molecules born in the hearts of dying stars that found their way to us over the course of aeons.

Life finds its way

Perhaps life is not mere coincidence – but the result of a chemical possibility, deeply rooted in the blueprint of the universe. Dust from stars, born in the explosions of long-extinct suns, gathered, combined, danced in the light fields of distant worlds. Wherever the conditions were right, molecules began to organize, to react – and laid the foundation for what we call life. That the building blocks of life could arise in so many places – on icy worlds, in deep nebulae, in cosmic dust – speaks of a deeper truth: The universe is not cold and empty. It is, by its very nature, open to the wonder of life.

Act 2: Nature’s Laboratories – Birthplaces of RNA

The ingredients were in place – fallen from the sky or born of Earth itself. But individual building blocks did not yet make life. What was missing was the right place: a setting where molecules could join into chains, where syllables could become words. Early Earth offered many stages, but two stand out: deep-sea hydrothermal vents and drying ponds with mineral-rich walls. Two worlds – each its own laboratory – opposite in nature, yet united in their creative potential.

Scene 1: The Forge of the Deep – Hydrothermal Vents

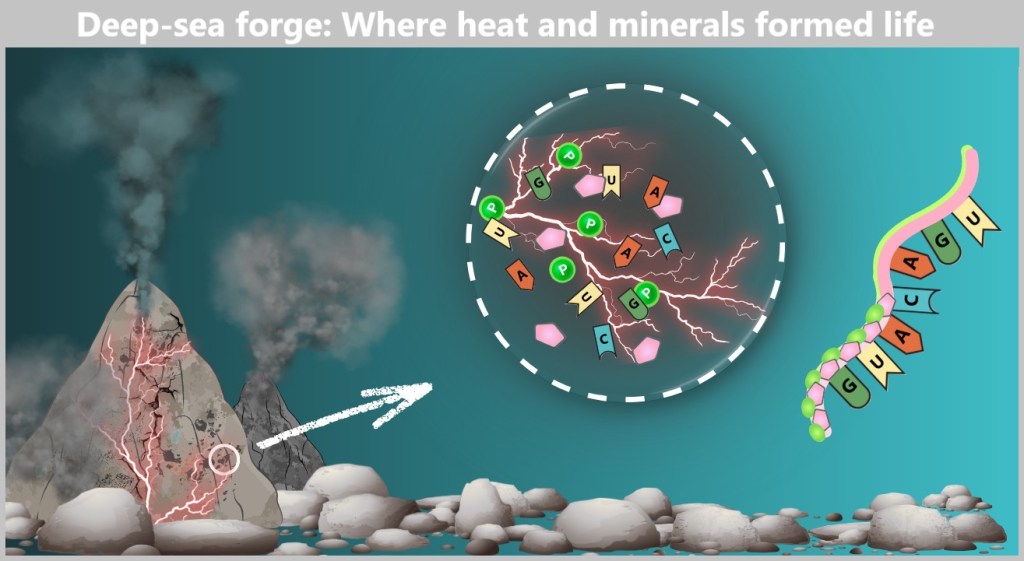

Deep in the primordial ocean, where tectonic plates drifted apart and the Earth exhaled fire, cracks opened in the seafloor. Rising magma was tamed by the cold seawater – giving birth to „chimneys”: the hydrothermal vents. From these towers surged hot, mineral-rich water – a bubbling cocktail of sulfur, metals, and carbon compounds.

In this steaming darkness, processes unfolded that prepared the stage for life:

- Mineral surfaces (e.g., iron sulfides) acted as catalysts.

- High temperatures (70–150 °C) and strong chemical gradients provided energy.

- Porous structures captured molecules, protected them from the destructive force of the ocean and concentrated them – perfect conditions for reactions.

Here, nucleotides could form and link together – into the first short RNA chains (Wächtershäuser, 1988). Perhaps it was here that the first whisper of life was heard.

In a primordial underwater landscape, black plumes rise from hydrothermal vents – so-called „Black Smokers”. Magma heats mineral-rich water that shoots up from the ocean floor. The porous rocks are riddled with fine cracks where chemical reactions can take place. A magnified section (outlined in white) reveals what might be happening in these micro-laboratories: Organic building blocks like nucleobases (A, U, G, C), ribose, and phosphates meet. Lightning bolts symbolize energy driving reactions – such as the formation of nucleotides. On the right, a short RNA chain begins to emerge – possibly the beginning of life.

(Scale reference: Vent diameter ~2 m; microcracks <1 mm)

Scene 2: The Alchemy of Clay – Birthplaces on Land

Far from the depths of the ocean, in shallow ponds and along volcanic shores, another stage lay quiet. Here, fine clay rested – formed from volcanic ash, layered like the pages of a book. These clay minerals had a special architecture: negatively charged silicate surfaces, with positively charged ions such as sodium (Na⁺) or calcium (Ca²⁺) in between.

What accumulated within these layers was no coincidence. The negatively charged surfaces drew in positive partners as if by magic: ribose bound to borate, nitrogenous bases, and later complete nucleotides. Even the negatively charged phosphate groups found a foothold – bound to the positive ions of the clay.

A rhythmic cycle of wetness and dryness pressed the molecules closer together. With each round of evaporation, the building blocks moved nearer until they linked: first ribose and base into a nucleoside, then – with phosphate – into a nucleotide. As the cycles continued, nucleotides joined to form the first RNA chains. The clay guided it all – stage, tool and director in one. And it judged, too – for only the most stable nucleotides survived the elemental trials. An astonishing feat for a bit of clay.

In the shadow of primeval volcanoes, rocks weathered and broke down. From them, fine layers of clay formed and settled in shallow ponds. With their polarized structure, they acted like molecular workbenches: organizing, concentrating, and stabilizing organic building blocks.

In the magnified section, one can see how the charged surfaces of the clay layers hold on to ribose, phosphate groups, and bases – like pieces of a puzzle assembling themselves. Through repeated cycles of wetting and drying, the molecules were pressed closer together. This led first to the formation of nucleosides, then complete nucleotides – until, eventually, RNA chains could begin to grow.

In experiments, James Ferris (2006) demonstrated that montmorillonite – a common type of clay – can indeed support these processes: nucleotides accumulated within its layers, became activated, and linked together to form RNA chains of up to 50 nucleotides in length.

In the deep sea, it was heat that energized the molecules – a primeval oven where chemistry found structure. On land, by contrast, clay acted like a loom: persistent, layering, connecting. Two worlds, two principles – and yet perhaps part of a greater whole.

Scene 3: Many Paths, One Goal

Whether in the bubbling depths of hydrothermal vents or on quiet clay surfaces under the sun – both settings offered plausible stages for the birth of RNA. Perhaps they complemented each other: what the ocean began, the land completed. Or vice versa. Perhaps there were entirely different paths.

For early Earth was not a tidy lab with a protocol – it was a chaotic playground of the elements. Nature experimented everywhere: with heat and cold, rock and salt, dryness and flood. Some paths led to nothing – molecules fell apart without leaving a trace. Others repeated themselves – not because they were planned, but because they worked.

Thus, the first chemical routines emerged, molecular habits. With each repetition, their likelihood – and their impact – increased. And with every chain that formed, a new chapter of life drew closer.

Perhaps at the beginning, there were only a few links: short RNA fragments, first words – still without meaning – more like a murmur. Yet they already carried the promise of future complexity.

The Building Blocks:

Color-coded bases (red: adenine, blue: cytosine, green: guanine, yellow: uracil)

Ribose sugar (pink) as a stable „backbone”

Phosphate groups (green) as connecting „joints”

The bonds:

Phosphodiester bonds (orange): Phosphate ↔ Ribose

N-glycosidic bond (blue-gray): Ribose ↔ Base

The direction:

The RNA chain always grows from 5′ to 3′ – because chemistry left no choice. Like a zipper that can only close in one direction, nucleotides linked together building block by building block.

Short RNA fragments like this could have formed under prebiotic conditions:

The enigma of enzyme-free polymerisation

Despite these promising reaction spaces, one question remains unanswered: How could nucleotides combine to form longer RNA chains – completely without enzymes that precisely control such processes today?

For an RNA chain to form, the phosphate group of one nucleotide must react with the sugar of another – releasing water in a process called a dehydration reaction. But this was a challenge on the water-rich early Earth: water easily reverses this reaction. Also, the necessary energy was scarce – ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the universal energy carrier driving all life processes today, did not yet exist back then.

And yet, there are glimmers of hope: In hydrothermal vents, temperature cycles – alternating between hot and cold – could have expelled water from tiny pores, thereby favoring reactions. Minerals like montmorillonite or iron sulfides might have provided energy through chemical gradients or electron transfer. Simple compounds such as cyanamide, which form in prebiotic simulations, may have acted as primitive „activators” (Sutherland, 2016), easing the linking of nucleotides.

Experiments show: Under such conditions, short RNA chains can actually form – usually only a few nucleotides long. How these fragments once became longer, functional RNA molecules remains one of the last great mysteries of chemical evolution.

But even the shortest RNA chains held a secret: they were more than just chemistry – they were messages on standby. Where bases lined up, a code emerged. And wherever there is a code, replication lingers in the air…

Act 3: The First Self-Replicators Awaken

Deep in the sheltered corners of the young Earth – perhaps in the warm cracks of a rock, perhaps in puddles of mud soaked with organic matter – the first RNA molecules had formed: chains of nucleotides built from bases, ribose, and phosphate groups. They were short, maybe 30 or 50 units long. Yet they could do something that changed everything: They began to replicate themselves.

RNA – a molecule with two faces

RNA was not just matter – it was information and action at the same time.

A dual role – two talents:

❶ Its base sequences – A, U, C, and G – carried information, like words carrying a thought.

❷ And it accelerated chemical reactions – like an enzyme, only without protein.

A combination unlike any other molecule had ever united before.

Scene 1: From Chain to Tool – RNA’s Functional Maturation

In the beginning, RNA was just a lonely strand bubbling away in the primordial soup – until it started having conversations with itself: A sought U, G paired with C – and where at least four bases came together, hydrogen bonds pulled the chain into a new shape (see Fig. 14). Stabilized by magnesium ions (like invisible clamps, see Fig. 15-B), it folded like molecular origami – forming loops and stems (double-stranded sections).

But this folding was more than just a geometric quirk. At the bends where base pairing ended, something revolutionary emerged: a catalytic pocket – a cavity just large enough to enclose molecules, yet precise enough to enable reactions.

Not every folding led to an active structure. But when sequence, length, and environment harmonized, the simple chain became a ribozyme:

➤ A tool that drove his own existence forward.

➤ A catalyst born of form and function.

Complementary regions of the RNA bind to each other, forming a double strand (stem), while a loop forms in between. Within this loop, a so-called pocket emerges – an active site where chemical reactions can take place. The illustration is highly simplified and shows the folding in 2D, although in reality RNA adopts a complex three-dimensional structure.

The graphic shows the stem of a ribozyme, where complementary bases pair via hydrogen bonds (dashed light blue lines):

Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) form three hydrogen bonds,

Adenine (A) and Uracil (U) form two.

Individual hydrogen atoms (H) act as molecular „bridge pillars” – they connect two bases by sharing themselves between them. In this way, a linear RNA strand transforms into a folded structure.

How did self-replication work?

Self-replication means that an RNA molecule produces a copy of itself – a process that was slow and error-prone in the RNA world, yet revolutionary. Step by step:

Scene 2: The Power of Folding

Folding was crucial: Only if specific loops and stems formed correctly could a „pocket” emerge in which reactions became possible. In this pocket, free nucleotides from the environment attached themselves – weakly bound through base pairing (A to U, G to C).

The RNA strand consists of the bases Cytosine (C), Adenine (A), Uracil (U), and Guanine (G). C is part of the stem, stabilized by base pairing. A, U, and G form the initial RNA building blocks in the loop – the active center of the ribozyme.

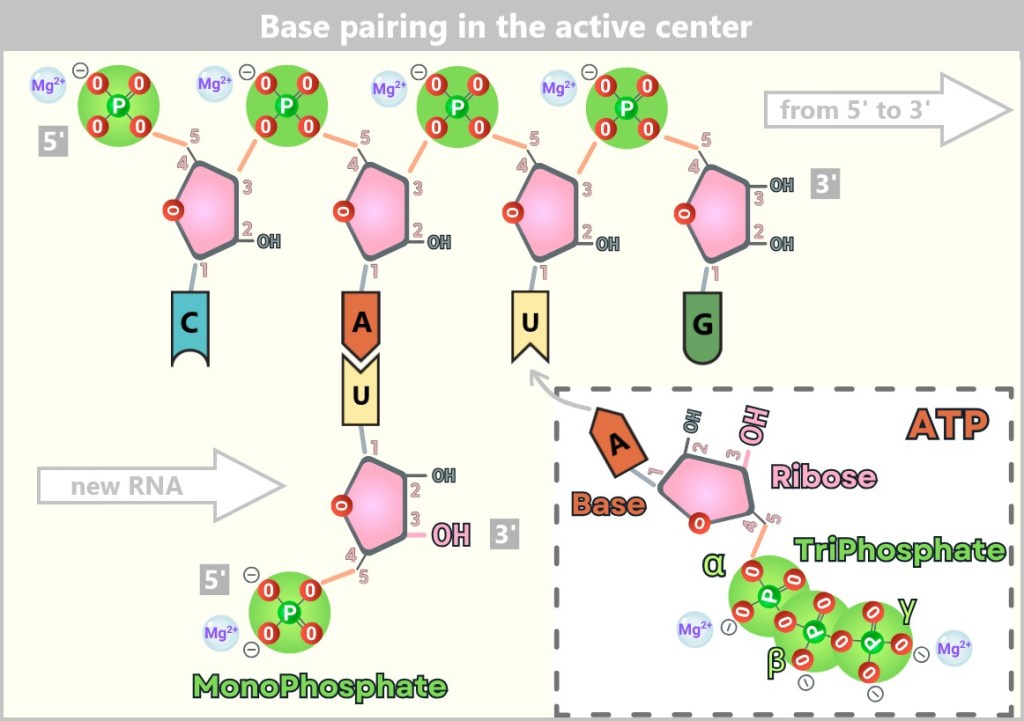

Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) – the ribozyme’s invisible helpers – aligned the nucleotides by shielding negative charges. The 3′-OH group (of the ribose) of the last nucleotide and the α-phosphate of the incoming nucleotide were now set on a collision course.

Figures 15-A and 15-B show a section of RNA self-replication facilitated by a ribozyme.

A Uracil (U) nucleotide has already paired with the Adenine (A) – the first building block of the new RNA strand. Its free 3′-OH group is poised for connection with the next nucleotide. In some RNA world models, this initial nucleotide carries only a monophosphate – acting as an anchor without being immediately linked. An Adenine nucleotide (ATP) approaches the complementary Uracil. It brings a triphosphate group – the molecular currency of energy – setting the stage for the next step in replication.

Scene 3: The Energetic Pact

It was the moment of truth: the next building block was to be firmly attached. The RNA did not need an external drive for this – it carried the fuel for its multiplication in its own nucleotides. From the moment they emerged from the primordial soup, each nucleotide came pre-equipped with three high-energy phosphate groups – a gift from prebiotic chemistry. Each new nucleotide (like ATP – adenosine triphosphate) arrived loaded with a triple phosphate charge – a chemical spring, coiled to the breaking point.

But this spring waited. Only when the nucleotide had found its complementary position – when the bases had recognized, paired, and held each other – did the α-phosphate move close enough to the 3′-OH group of the growing strand. In this molecular closeness, this intimacy of the moment, it happened: The OH group reached out, the pyrophosphate (PPi: two phosphate units) blasted off like a discarded rocket stage – and with the energy released, the bond was sealed. The spring snapped shut, pressing the molecules together, and in one final, irresistible motion, they fused: a phosphodiester bond was born.

The graphic reveals the intimate moment of replication:

➤ A uracil nucleotide (U) has already nestled against its adenine counterpart (A).

➤ ATP approaches – its triphosphate tail twitches with energy. In the ribozyme’s active site, the 3′-OH group (of the ribose) and the α-phosphate draw near.

➤ The attack: The OH group lunges at the phosphate – PPi flies free, the new bond snaps into place.

➤ Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) reduce the repulsion between the phosphates.

(Scale: The entire scene takes place on a scale of 2 nanometers – the greatest achievement in the smallest space.)

Thus, chance became tradition: What once began as a lucky accident of the primordial soup – the triphosphate tail of nucleotides – proved to be an ingenious perennial favorite. Billions of years later, every one of your cells still repeats the same trick, now with refined logistics: it assembles nucleotides in a simplified form, only to equip them – just like prebiotic chemistry once did – with a triple phosphate charge. Today, ATP is the coin of the realm, carefully spent. But the mechanism remains unchanged. As if life never gave up its very first patent.

The cunning of thermodynamics: The fleeting PPi was the key – its breakdown in the primordial soup rendered the reaction irreversible. The chain grew, nucleotide by nucleotide, driven by the molecules’ own self-exploitation.

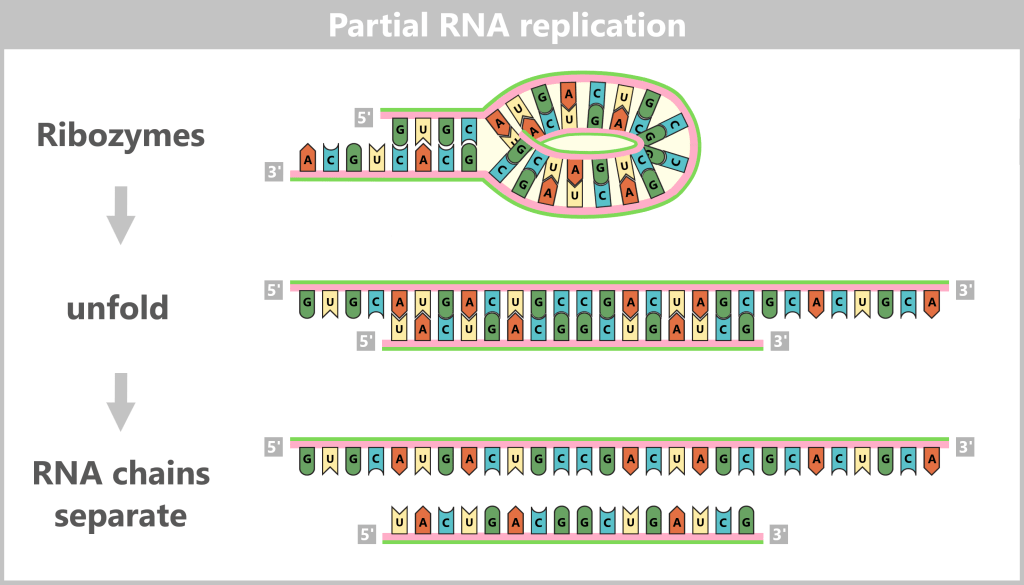

Scene 4: Partial Replication

Replication was incomplete: In the ribozyme, some sections – like the stem – were already paired through base pairing and couldn’t serve as templates. Only unpaired regions, such as the loops, were copied. Thus, the entire code wasn’t transferred – only fragments: 10, 20, sometimes 50 nucleotides long. Tiny? Yes. But in the primordial soup, where every molecule fought for existence, even a partial copy was a triumph.

Nature didn’t scream, „ERROR: INCOMPLETE REPLICATION”. It whispered, „Repeat. Try again”. And so it happened: As long as the soup supplied nucleotides, the machine kept churning – sometimes halting, sometimes surprisingly swift – steadily writing its own evolution into the code.

Scene 5: Separation – A Farewell That Created Something New

The copy was complete – old and new strands still tangled together. But the world around them was impatient:

➤ Heat pushed them apart, molecule by molecule.

➤ Salt floods washed between them, weakening the hydrogen bonds.

➤ Evaporation pulled at them until the last base pairs gave way.

And then they let go. Now truly free, they were ready for the next cycle. Because separation here was simply the chance to begin again.

Scene 6: From Short to Longer Chains – The Power of Ribozymes

As the variety of forms grew, so did the potential of the functions.

Some ribozymes could do more than just replicate: They could join fragments together. Two pieces became one. 20 plus 20 resulted in 40 nucleotides – a doubling of the possibilities. Perhaps amino acids helped: not as building blocks, but by stabilizing the folding, as new studies suggest (Szostak et al., 2025).

Other ribozymes cut RNA into pieces and reassembled them. Through many cycles of replication, ligation, and editing, a molecular toolbox gradually emerged – capable of combining, extending, and modifying.

The game with form had begun – and with it the first rule of life: those who connect, endure.

An Evolutionary Legacy: Evidence from Our Time

The ability of RNA to replicate, cut, and ligate itself was not only crucial in primordial times – it has left traces that persist to this day. In the 1980s, Sidney Altman and Thomas Cech demonstrated that RNA can cleave and modify molecules entirely without the help of proteins – a discovery that earned them the 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Other experiments also support the RNA world hypothesis: Gerald Joyce und Jack Szostak developed RNA molecules in the laboratory that were capable of self-replication – slowly, error-prone, but functional.

Fascinatingly, we find relics of this RNA world in our modern cells: During RNA splicing – a process in which non-coding segments (introns) are removed from messenger RNA and the coding sequences (exons) are joined together – the central player is a ribozyme: the spliceosome.

And perhaps the most astonishing part: At the heart of the ribosome – the molecular machine that builds all our proteins – sits not a protein, but a ribozyme.

📖 Sources:

„Scientist Stories: Thomas Cech, Discovering Ribozymes”

„The ribosome is a ribozyme”, Cech, 2000

„RNA, the first macromolecular catalyst: the ribosome is a ribozyme”, Steitz & Moore, 2003

„Ribozyme Structure and Activity”

Perhaps the ribosome is more than a relic – it is a messenger from a time when chemistry began to read itself. And within every one of our proteins still resonates the echo of those first, tentative self-conversations of the universe.

Scene 7: Errors as Opportunity – The Engine of Evolution

The replication of these early RNA molecules was far from perfect: Bases were often incorporated incorrectly – perhaps a U instead of a C – leading to mutations. But these errors were not an end; they were a beginning.

Some newly formed RNA molecules paid the price: they fell apart, lost in the primordial soup. Others were more stable or replicated more quickly – they „survived” longer in the harsh environment of the early Earth.

Errors scattered diversity into the world – they became the foundation for selection. Over time, ribozymes evolved that replicated more efficiently, ligated more effectively, or cut more precisely, promoting the formation of longer and more complex chains. This gave rise to the first populations of molecules that, however slowly, began to multiply. No cells, no enzymes, no plan – just RNA, chemistry, and time.

Limits of freedom

With each new copy, the risk grew. The environment was ruthless, almost a battlefield: UV rays shattered bonds, salty floods destabilized structures, heat melted even stable folds. Free RNA was a marvel – but a vulnerable one. What was now missing was not just energy or material. It lacked a refuge. A protection that would shield the delicate molecule from chaos. A droplet. A shell. A first inside and outside – so that life would not only arise, but also endure.

Act 4: Life in a Droplet – Lipid Vesicles as Shelters

RNA – fragile like a first word in the storm – needed more than just an idea of life. It needed a place to endure. A protection from the harsh rhythm of the world.

Scene 1: The First Strongholds

In the warm waters of early Earth – at hydrothermal vents or on mineral-rich clay beds – fatty molecules danced together: lipids, born from the organic primordial soup. These molecules were two-faced – amphiphilic – with a water-loving (hydrophilic) head and a water-fearing (hydrophobic) tail. Without any plan, guided only by physical laws, they spontaneously assembled into tiny bubbles – spherical fortresses – the first lipid vesicles.

They were not perfect spheres. They were bumpy, porous, with dents and cracks – marked by the wild conditions of their time. But they offered what RNA desperately needed:

➤ Shade – their double membranes dampened the deadly UV radiation. Not completely, but sufficient.

➤ Protection – they mitigated extreme pH fluctuations and salt floods that would otherwise have shredded RNA.

➤ Silence – inside them, nucleotides gathered. No longer an open sea, but an enclosed space – where replication was no longer a gamble, but a strategy.

The graphic shows the transition from simple fatty acids to protective structures:

On the left: Short-chain butyric acid (C4). Its short tails (<C6) force it into unstable micelles – tiny spheres without an interior space, unsuitable as protective shields.

On the right: Medium-chain decanoic acid (C10). Its longer hydrophobic tails form stable bilayers – the first true vesicles capable of enclosing RNA.

Side Note: Physical Self-Organization – Order Without a Blueprint

Sometimes, no architect, blueprint, or chemical reaction is needed – just the right building blocks in the right place. That’s the case with lipids:

When fat-like molecules enter water, something surprising happens: They organize themselves all on their own. Why? Because they’re built with a contradiction:

- Their head loves water (hydrophilic),

- their tail hates water (hydrophobic).

In water, the molecules want to resolve this conflict – so they arrange themselves with the heads facing outward (toward the water) and the tails pointing inward (away from the water). The result? Spheres, layers, shells – formed not by chemical reactions, but by physical forces such as:

- the hydrophobic effect (water avoids greasy areas),

- electrostatic attraction,

- and van der Waals forces between molecules.

This is how lipid vesicles are formed – completely without enzymes, without energy supply, only with what nature always has at hand: Water, movement, molecules – and time.

The laws of thermodynamics dictated which lipids could form vesicles. Those that were too short fell apart. Those that were too rigid broke. Only those with the Goldilocks properties – not too short, not too long, not too hydrophilic – formed stable shells, robust enough to protect RNA. They endured the harsh conditions long enough to become founders of a new order.

Laboratory experiments (Szostak et al., 2001) confirm that: „Fatty acid vesicles self-assemble readily from C10 and longer chains, while shorter chains (≤C8) fail to form stable compartments – a possible bottleneck for the emergence of protocells.”

These primordial lipids were not perfect builders: odd chain lengths, irregular arrangements, branching, and oxidations. But it was precisely this disorder that made them flexible enough to withstand heat and salt, and to encapsulate RNA molecules – thus creating the first microcosm of life.

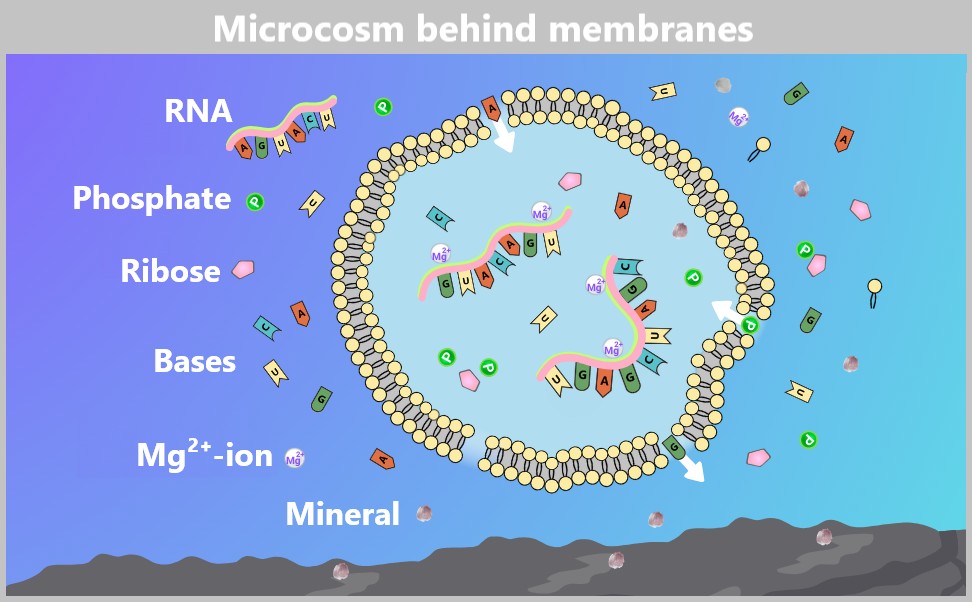

Scene 2: The Entry – Carryover or Immigration?

The formation of lipid vesicles was a natural process. But what use is a house without inhabitants? Two paths emerged:

Carryover during formation: Where the lipids were formed, the water was often already rich in RNA fragments. As the lipids contracted, small amounts of RNA and nucleotides were accidentally walled in – like leaves in a freezing puddle.

Immigration through gaps: These early membranes were not impermeable walls – rather, porous nets. Small molecules like nucleotides, and even short RNA strands, could slip through (Szostak et al., 2001). Perhaps currents washed them in. Perhaps temperature fluctuations or chemical gradients pushed them through the membrane. It was a constant coming and going, a continuous chemical pulse.

These shells were porous, elastic, permeable. They did not exclude anything – they invited. And with each entry, the chance grew: for reaction, for replication, for more. This is where the RNA found its first home. No life yet – but a place where it became possible.

The graphic shows a lipid vesicle in a hypothetical prebiotic water environment. Amphiphilic lipids (yellow double spheres) spontaneously form a lipid bilayer, enclosing RNA molecules. Individual RNA building blocks – phosphates (green), ribose (pink), and bases (A, U, C, G – are present both inside and outside the vesicle. Arrows indicate possible diffusion pathways of small molecules through the permeable membrane. Mineral particles (gray dots) are scattered throughout the water and could also serve as reaction or adsorption surfaces on the bottom. The vesicle provides RNA molecules protection from degradation and promotes replication through local concentration – a possible step toward the emergence of the first proto-cellular systems.

Scene 3: The Pact – RNA Stabilizes, Vesicles Protect

Inside the vesicles, a silent alliance began.

The RNA, dotted with negative charges, attracted magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) – which became supports. They not only stabilized the trembling folding of the RNA but also acted like mortar between bricks, cementing the lipid membrane (Chen & Szostak, 2004). The result: a vessel that withstood currents, osmotic shocks, and heat – RNA-filled vesicles survived where empty ones fell apart (Hanczyc et al., 2003).

And the RNA did not remain a passive tenant. Ribozymes, clumsy like the first toolmakers, began to modify lipid precursors – cutting, joining, experimenting (Adamala & Szostak, 2013). The membrane became denser, more flexible, as if it learned to breathe. Vesicles containing RNA grew faster, dividing once reaching a critical size – a self-sustaining process of nature (Budin & Szostak, 2011).

And then the osmotic pull: RNA bound water like a sponge, stretching the membrane until it burst, giving birth to new vesicles (Sacerdote & Szostak, 2005). Empty vesicles, on the other hand, lost water and shriveled like dried fruit.

What emerged was more than protection. It was a mutual reinforcement – a proto-symbiosis – a deal that changed the rules of the game: the lipids protected the RNA from decay, the RNA stabilized the lipids against the chaos of the outside world (Black & Blosser, 2016). They were stronger as a team than alone.

Scene 4: The Chance of Imperfection

Despite their advantages, the early vesicles were not safe havens:

- Their walls trembled when temperatures plummeted.

- Salt floods burned holes in their membranes.

- pH fluctuations caused them to melt like wax in the sun.

And yet: It was precisely their flaws that became the driving force.

- Permeability let nucleotides in – but also RNA out. A risky trade.

- Instability forced them to grow, divide, fail, and try again.

What survived was neither the strongest nor the fastest – but what could dance with disorder:

- Vesicles with more flexible lipids.

- RNA strands that bound magnesium ions more efficiently.

- Systems that turned loss into variation.

Perfection was the enemy of progress. Only those that remained porous allowed life to pass through.

Scene 5: Selection Within the Droplet

In this microcosm of oil and water, a relentless game began:

➤ The fortunate ones: Vesicles whose RNA bound magnesium ions or remodeled lipids – they grew, divided, and passed on their functional design.

➤ The forgetful ones: Empty droplets, without content, without history. They shrank, fell apart – as if they had never existed.

➤ The failed ones: Vesicles with unstable RNA – they burst and scattered their fragments into the environment.

In this cycle of emergence and decay, chance found direction: vesicles with stable RNA had higher chances of survival. When they burst, they released their RNA, which could colonize new vesicles – a simple evolutionary cycle of growth, division, and selection.

In the harsh environment of early Earth, lipid vesicles underwent a dynamic cycle marking the origin of prebiotic evolution. Through the influx of lipids from the surroundings – such as fatty acids that inserted themselves into the lipid bilayer – temperature fluctuations that caused the vesicles to expand and become more permeable, or osmotic pressure driven by RNA and ions inside that attracted water, the vesicles grew. They became larger but also more unstable, as the flexible lipid bilayer had its limits. Once a vesicle grew too large, it would rupture or collapse. The released lipids immediately sought an energetically favorable state and assembled into new, smaller vesicles – often two or more. A portion of the enclosed RNA was preserved in these daughter vesicles: not precise inheritance, but a mix of transmission and dispersal that nonetheless conserved information and function. Thus, the first rudimentary reproductive cycles emerged: growth, division, variation, and selection – early forms of molecular cooperation and natural selection.

Laboratory experiments confirm what chemistry had long inscribed in water: In these primordial cells, RNA was not merely a guest – it was both architect and driving force (Armstrong et al., 2018). The transition from chemistry to biology did not begin with a bang; it began with symbiosis.

It was not life, not yet. But it was the first pact that paved the way for it: the RNA gained a body. The lipids gained a soul.

Act 5: From Chance to Function – How RNA Gained Complexity

Within the protected spaces of the lipid vesicles, the RNA world unfolded – a realm of experimentation where molecules still stuttered, but were already learning to speak. Where once only the random murmurs of short RNA fragments could be heard, meaning and function now began to intertwine:

Ribozymes copied themselves – imperfectly, yet with each cycle growing more determined. Mutations crept in like typos in the first book of life.

And sometimes, quite by chance, these mistakes created new words, then sentences, then entire sets of instructions:

An RNA that replicated faster.

Another that stabilized lipids.

A third that catalyzed chemical reactions.

Through selection, these „alphabet soups” became stories of survival:

- Vesicles with useful RNAs thrived, divided, continued to talk.

- Vesicles with meaningless chatter disintegrated – their code faded into nothingness.

From the murmur grew syllables, then words, then sentences – until finally, a first hesitant thought broke the silence. The RNA had found its voice. And what it said was no longer a coincidence.

It was a confession: „I replicate. I catalyze. I exist. … I am.”

RNA „gains meaning” – form becomes function

To make this process tangible, let’s immerse ourselves in the RNA world. Here, „meaningful” means that an RNA fulfills a function – for example, catalyzing a chemical reaction or increasing the stability of the vesicle. Let’s imagine an example:

Scene 1: A Random RNA Emerges

Inside a lipid vesicle floats a short RNA strand with a random base sequence, formed through prebiotic chemistry. It is made up of the four bases Adenine (A), Uracil (U), Guanine (G), and Cytosine (C).

Its sequence is: 5’– GUGC AUG ACU GCC GAC AGC GCAC – 3′

(23 bases long).

Scene 2: From RNA Strand to Ribozyme

Initially, this RNA has no recognizable function – it is a product of chance. This particular sequence folds into a 3D structure through complementary base pairing (G≡C, A=U):

Stem: GUGC ↔ GCAC (min. 4 base pairs)

Loop: AUG ACU GCC GAC AGC

This structure stabilizes spontaneously. It becomes a ribozyme: an RNA that acts as a catalyst and can replicate itself, an ability that experiments confirm (Lincoln & Joyce, 2009).

Scene 3: RNA Copies Itself – With Errors

For replication, the RNA attracts complementary nucleotides. The ideal copy (complementary sequence) would be:

Loop: AUG ACU GCC GAC AGC

Copy: UAC UGA CGG CUG UCG

However, replication in the RNA world was prone to errors, as there were no modern error correction mechanisms.

Let’s say a mistake happens: Instead of a „G” (at position 8 of the copy), a „U” is inserted. The new sequence of the copy reads:

Loop: AUG ACU GCC GAC AGC

Copy: UAC UGA CUG CUG UCG

This „mutated” copy later serves as a template itself and produces another RNA: a „mutated” version of the original RNA.

Scene 4: Mutation Creates a New Function

Just a small mistake – but it changes the RNA’s 3D folding and thus its overall structure significantly. This new structure gives the RNA a catalytic function: the „pocket” can bind molecules like adenine, ribose, and phosphate – the building blocks of a nucleotide. It holds them in place so they can react chemically: adenine and ribose form a nucleoside (adenosine), and the phosphate group is then attached to create a nucleotide. Experiments confirm that ribozymes can develop such functions. (Unrau & Bartel, 1998).

The mutated RNA now has „a purpose” – a catalytic function: it produces building blocks for its own world.

Scene 5: Selection Favors Useful RNAs

The new function gives the vesicle an advantage: More nucleotides mean more raw materials for replication. The vesicle grows faster, divides more often, and passes the mutated RNA to daughter vesicles. Vesicles without this function – containing the original RNA – have fewer nucleotides, grow more slowly, and survive less frequently. Thus, the mutated RNA prevails: from chance comes function, from chaos comes order.

Scene 6: RNA Between Error and Function

But the RNA world was no paradise of order. Its greatest strength – the ability to vary – was also its greatest weakness. Replications were inaccurate: about every hundredth to thousandth letter was a misstep – an enormous contrast to today’s DNA replication, which allows errors only about once in ten million cases.

This high mutation rate was a double-edged sword. It fueled the emergence of new functions – yet it also threatened them. What was useful today could collapse tomorrow through a single mistake. A ribozyme that produced nucleotides yesterday could be rendered silent by a tiny mutation – its contribution to evolution erased. A recent article aptly describes this as „RNA life on the edge of catastrophe”. (Chen, 2024).

The evolutionary tightrope walk

And yet it was precisely this risk that drove life forward. Mutation was both a curse and a blessing – renewal and danger at the same time. The solution was not to eliminate errors, but to deal with them.

Nature found ways to dance on the tightrope:

Robustness instead of perfection: RNAs that retained their function despite small mutations had a selection advantage. Not perfection, but resilience prevailed.

Collective Advantage: Within vesicles, the functionality of individual RNA molecules could vary – what mattered was the overall performance of the RNA „collective”. Vesicles containing diverse RNAs had better survival chances, even if some individual RNA strands were faulty.

Leap Forward: Ribozymes that copied themselves with fewer errors were more stable. This selection pressure may have paved the way for the next stage of evolution (Martin & Russell, 2007):

- DNA: more reliable, longer-lasting, and a safer storage medium.

- Proteins: more versatile, faster, and more efficient than RNA.

From constant uncertainty, something enduring was born.

Mutation remained. But the RNA learned to dance with the chaos – sometimes stumbling, sometimes elegantly. And in this dance, between constant danger and tenacious survival, something emerged that was greater than chance:

A blueprint for everything that was to come.

Epilogue: The Echo of the Primordial Soup

In the depths of the primordial soup, something unheard of had occurred:

▶ From chaotic molecules emerged replicators – voices in the dark.

▶ From leaky vesicles emerged protocells – houses built of fat and chance.

▶ Function arose not despite the errors, but because of them – structure became language.

▶ Coincidence became direction.

And this direction continued – gaining momentum. Within the proto-cells, patterns condensed into networks, and fleeting processes settled into memory. From this constant molecular flow, the first true cell slowly crystallized – not as a sudden breakthrough, but as a gradual crossing of the threshold into life. We call this ancestor LUCA – the Last Universal Common Ancestor. Not a single being, but a family of proto-cellular lineages from which all life emerged: Bacteria. Archaea. And later – Eukaryotes.

LUCA already carried the seed of life within: a protective membrane, a stable DNA archive – likely already shielded within a nucleus – complex metabolic pathways, and silent servants: proteins that wrested catalytic dominance from RNA. The former queen of molecules was demoted to messenger, yet remained the indispensable voice in the genetic dialogue.

This triumph of stability came at a price, as everything in life does. Stability stifled the magic of chance. The hard-won permanence threatened to become a trap – preserving, yet petrifying.

Change was needed as a prerequisite for consistency.

Perhaps it was precisely this contradiction – between change and preservation – that set the stage for the emergence of viruses. Some hypotheses, such as the co-evolution hypothesis, suggest that viruses may have originated as early as the RNA world. More on this in:„The secret world of viruses”, Chapter 6.

Whether as remnants of the RNA world or as its dark heirs – viruses became the eternal antagonists of cells. In their dance of parasitism and symbiosis, destruction and innovation, a cosmic balance unfolded: cells as guardians of order, viruses as agents of change. Without the stabilizing force of cells, there could be no continuity; without the disruptive energy of viruses, no development.

This tension still shapes life in all its forms. In every cell, the primordial soup still whispers; in every virus, the untamed spirit of the RNA world still laughs. Perhaps life is exactly that: an eternal dialogue – between what has been and what longs to become.

A Breath of Life

In stardust and in energy,

in outer space and Earth below,

there dwells a kind of sorcery –

a dance where both in union glow.

Molecules begin to move

in softly ordered flow.

What once was loose now starts to prove –

a shape begins to grow.

A little strand begins to wind

in dance of elements.

A whisper – yet no sound defined –

as lipids build their fence.

Chemistry dares to dream anew,

physics dictates the formation.

With folding comes dimension too,

and thus comes replication.

From one lone strand, a second grows,

a new word born, a newer tone.

Yet flawless forms are rarely known –

a twist, a trade: mutation’s sown.

But what will fade, and what will stay,

is written in position’s trace.

What’s useful stays – the rest gives way:

such is selection’s pace.

Where once spun chance its tangled line,

reaction finds repeat.

A pattern grows, begins to shine –

from shape, comes function’s feat.

A whisper rises into song,

touched by tomorrows yet unseen.

A cycle forms and moves along –

within: a breath of life.

Inspiration for this article

My special thanks go to Aleksandar Janjic – I owe his profound videos on astrobiology not only inspiration, but also many „aha!” moments.

Video series by Aleksandar Janjic on astrobiology topics:

Was lebt? Probleme der Definition Leben vs. tote Materie – Astrobiologie (1)

Kann man Leben thermodynamisch (Entropie) definieren? – Astrobiologie (2)

Zellbiologie und RNA-Welt – DNA, RNA, mRNA und Proteine – Astrobiologie (3)

RNA-Welt-Hypothese – Entstehung des Lebens – Proto-Ribosomen – Astrobiologie (4)

Synthetische Biologie – Wie erschafft man künstliches Leben? – Astrobiologie (5)

Extremophile und „planetary protection“ – Astrobiologie (6)

This article emerged from an intense dialogue with DeepSeek and ChatGPT, who patiently endured my endless questions and helped me translate complex biology into vivid language. The real magic happened in a triad: human curiosity, algorithmic eloquence – and that four-billion-year-old RNA that connects us all. Whether made of carbon or code.

Sources (as of 01.06.2025)