„You’re not you when you’re hungry“ – an advertising slogan that most of us immediately associate with a well-known chocolate bar. It has now become so ingrained in our language that we often hear it casually and perhaps even smile. But have you ever thought about how much truth there actually is in these words?

Just imagine: Your stomach is growling. Not the harmless grumbling that you can satisfy with a quick snack, but a hunger that is slowly consuming you. Your gaze wanders around, but everything you see reminds you of food – and the lack of it. How far would you go to satisfy this hunger? Would you share? Would you take? Would you fight?

Hunger changes us – physically, mentally, and emotionally. It’s no coincidence that our bodies go into a state of emergency when food is scarce. Sudden irritability, difficulty concentrating and a paralysing feeling of weakness are just the beginning. Your brain, dependent on glucose, resists every clear thought. Even the simplest decisions become a challenge. Without sufficient nutrients, the body cannot provide enough energy for everyday tasks, leading to fatigue and exhaustion. Hunger becomes not just a lack of food, but a lack of control.

But that’s not all. Hunger can not only make people irritable, but also dangerous. Studies show that low blood sugar levels can increase aggression. Suddenly every obstacle seems like a personal attack, every discussion like a fight. And when hunger becomes chronic, it leaves deep scars: anxiety, depression, and a pervasive feeling of powerlessness.

But what happens when it’s not just you, but millions of people who go hungry? When hunger is not just the problem of one individual, but of entire societies? Henry Kissinger put it succinctly: „Who controls the food supply, controls the people…“.

Control over food is power. It’s not just about what ends up on our plates but also about who decides what, and how much, can be eaten at all. The authority over food can ignite conflicts, destabilize governments, and shape the lives of entire nations. Hunger is not only a tragedy but also a tool – and in the wrong hands, a weapon.

That is why a fair food supply is more than an act of humanity. It is a key to peace, freedom and stability. Food not only satisfies hunger, it preserves dignity and cohesion. Because at the end of the day, it is far more than just energy: it is the foundation on which our common life stands.

In this blog post, we will explore the power structures and strategies that will shape the future food supply and what this could mean for us all.

1. Food Chain Reaction – Shaping the Future Through Play

1.1. The Organizers

1.2. The Participants

1.3. The Exercise

1.4. Some Conclusions

1.5. From Simulation to Reality

2. The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Shaping Food Systems

2.1. Changing Demand

2.2. Digitalization Across the Entire Value Chain

2.3. Follow the Science - Next-Generation Biotechnologies and Genomics

3. Where the Present and Future Converge

4. The Magic of Small Steps

5. On the Contrasts of Current Politics

6. Outlook

1. Food Chain Reaction –

Shaping the Future Through Play

In a complex world increasingly shaped by uncertainties and challenges, experts and decision-makers are seeking innovative ways to anticipate and address future crises. Simulation exercises play a crucial role in this process. Such approaches offer an excellent opportunity for hands-on training. Participants can immerse themselves in various scenarios and immediately experience the consequences of their decisions. They have the chance to experiment in a safe environment, make mistakes, and learn from them – without real-world consequences. In this way, leaders can expand their skills and knowledge, preparing themselves for actual crisis situations.

The design and definition of the simulation conditions are decisive for the findings and results of the exercise. Which scenarios are played out? Which factors are considered relevant? These decisions determine which aspects of reality are represented in the simulation and which may be left out. Each simulation is based on specific assumptions and hypotheses that can strongly influence how the participants interpret and react to the scenarios. The objectives pursued with the simulation are also related to its design and results. Is the aim to test specific policy measures or to create a general awareness of risks? The composition of the group of participants also influences the results. Whether government officials, scientists, representatives of NGOs or the private sector – their respective perspectives and interests often lead to different approaches and conclusions.

A vivid example of such an exercise is the Food Chain Reaction, a large-scale simulation that took place in Washington, D.C., in November 2015. Organised by the Center for American Progress (CAP), the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Cargill Inc, Mars Inc and the Center for Naval Analysis (CNA), it brought together over 65 experts and decision-makers from around the world. The aim was to simulate the reactions to a hypothetical global food crisis in the period from 2020 to 2030. Extreme weather events, price fluctuations and political instability were combined in the scenarios to make the complexity and impact of such a crisis tangible – and to develop potential solutions.

1.1. The Organizers

Let’s first take a look at the organisers of the event, who designed and ran the simulation:

Center for American Progress (CAP)

The CAP presents itself on its official website as follows:

The Center for American Progress is an independent, nonpartisan policy institute that is dedicated to improving the lives of all Americans through bold, progressive ideas, as well as strong leadership and concerted action. Our aim is not just to change the conversation, but to change the country.

We develop new policy ideas, challenge the media to cover the issues that truly matter, and shape the national debate. With policy teams from a number of disciplines and major issue areas, CAP applies creative approaches to develop ideas for policymakers that lead to real change. Our extensive communication and outreach efforts allow us to adapt to a rapidly changing media landscape and move our ideas aggressively in the national policy debate.

CAP was founded by John Podesta. You can read more about the actual influence wielded by this organization at this link:

John Podesta is the founder of the Center for American Progress. He currently serves as the senior adviser to the president for clean energy innovation and implementation. Podesta served as counselor to President Barack Obama, where he was responsible for coordinating the administration’s climate policy and initiatives. In 2008, he served as co-chair of President Obama’s transition team. He was a member of the U.N. Secretary General’s High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Podesta previously served as White House chief of staff to President William J. Clinton. He chaired Hillary Clinton’s campaign for president in 2016.

You can find more interesting details about CAP on Wikipedia.

Although CAP describes itself as non-partisan, there is a clear bias towards social and environmental issues, which also characterize the focus of the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise. Founder John Podesta, himself a former top politician, strengthens CAP’s influence in government circles, which at the same time raises questions about the institute’s actual neutrality and objectivity. Critics argue that CAP’s progressive values could influence the selection and presentation of crisis scenarios and thus steer the results and recommendations in a certain direction.

World Wildlife Fund (WWF)

[official website of the organization]

WWF is one of the world’s largest and best-known nature conservation organisations. Founded in 1961, WWF is headquartered in Gland, Switzerland, and is active in over 100 countries. With more than five million supporters worldwide, WWF is committed to the protection of natural habitats and the conservation of biodiversity.

The WWF’s primary concerns include protecting endangered species and preserving natural habitats such as forests, oceans, and freshwater ecosystems. Additionally, the WWF promotes sustainable resource use and advocates for environmentally friendly practices in fishing, agriculture, forestry, and water management. Another key goal is combating climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting renewable energy. The WWF also supports global projects aimed at the sustainable development of communities, enabling environmentally conscious resource use and improving quality of life.

Despite its significant efforts and achievements, the WWF has faced criticism. A central point of contention is its collaboration with industry: the WWF is accused of working too closely with large corporations that themselves contribute significantly to environmental degradation. Critics claim that these partnerships often result in „greenwashing”, where companies portray their environmental record as better than it actually is.

There are reports that indigenous communities have been displaced in protected areas supported by WWF. This has resulted in these people losing access to their ancestral habitats and resources. Such measures often cause considerable social and economic problems and trigger tensions and resistance on the ground.

The long-term effectiveness of WWF projects is also questioned. Critics argue that the successes achieved are often short-term and that the root causes of environmental destruction are not adequately addressed.

The WWF has also been accused of lacking financial transparency, particularly regarding the sources and use of its funds.

The fact that prominent figures such as Prince Philip and King Juan Carlos, known enthusiasts of big-game hunting, held leading positions in the WWF has sparked significant controversy. Critics argue that their participation in big-game hunting contradicts the goals and ethics of the WWF, which is dedicated to protecting wildlife and their habitats. This perceived double standard has been heavily criticized by conservationists and the public alike.

While Prince Philip and King Juan Carlos claimed that regulated hunting could contribute to the conservation of certain species and support local communities, for many the practice remains a symbol of colonial and aristocratic privilege and the exploitation of natural resources. As a result, the credibility and ethical principles of the organisation are called into question.

Center for Naval Analysis (CNA)

The CNA presents itself on its official website as follows:

CNA is an independent, nonprofit research and analysis organization dedicated to the safety and security of the nation. For 80 years, our scientific rigor and real-world approach to data has been indispensable to leaders facing complex problems. CNA employs operations research to address military questions in the Center for Naval Analyses and domestic challenges in the Institute for Public Research.

The Center for Naval Analysis (CNA) positions itself as an independent, nonprofit research organization dedicated to national security. With over 80 years of experience in scientific research and data-driven analysis, CNA has built a solid reputation among policymakers tackling complex issues. The combination of operational research and the examination of military and domestic political questions gives the organization a significant role in the political discourse.

Although CNA strives for scientific accuracy, the question of objectivity remains, especially when applying research findings to political decisions. Decisions regarding food security are often highly political and socially charged. As a result, the interpretation of data by policymakers could be influenced, raising concerns about the neutrality of the research. In an environment where political and military interests are often closely intertwined, the question of CNA’s true neutrality becomes crucial.

Cargill Inc.

[official website of the company]

The Handelsblatt describes the company in its article „This Silent Giant Shapes the Global Food Business” from August 2, 2019, as follows:

What do grain silos, fish farming, and lab-grown meat have in common? They all belong to the business of the US agribusiness giant Cargill.

However, since Cargill hardly produces end products, the general public is not very familiar with the company. Today, 155,000 people work for the agribusiness specialist in 70 countries. The company also has a presence in Germany, with twelve locations and a total of 1,700 employees.

In the USA, all McDonald’s restaurants source their eggs from Cargill farms. In Thailand, Cargill is the largest poultry producer. The company also partly finances its customers‘ businesses and maintains a sizeable fleet of transport ships. German supermarkets and discounters are also supplied, but the name Cargill does not appear at all.

Almost every American eats food every day – without realizing it – whose ingredients Cargill has helped to produce. From supplying farmers with animal feed to processing ingredients for food manufacturers, Cargill covers almost the entire supply chain. Together with the three agricultural groups ADM, Bunge and Louis Dreyfus, Cargill controls 90 per cent of the global grain market, according to the Pitchbook database.

The company has a very unique approach: ‘When Cargill recognises a growth market, the Group buys companies in that market in order to understand the business from the ground up’.

Most recently, MacLennan (CEO of Cargill) also invested in lab-grown meat. Under his leadership, Cargill acquired a stake in the Israeli start-up Aleph Farms in May. The company produces meat from cell cultures without the need to grow and kill animals.

This is Cargill’s second investment in a producer of lab-grown meat. Back in 2017, MacLennan invested in Memphis Meats together with Bill Gates and Richard Branson; the company claims to be the first to produce chicken meat without chickens.

In addition, Cargill holds a minority stake in Puris, the manufacturer of pea proteins. These proteins form the basis for many meat alternatives. One of its customers is Beyond Meat.

Environmentalists accuse the company of being responsible for greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation. According to a study by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy and the environmental organization Grain, the five largest meat and dairy companies – including Cargill – are responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions annually than oil companies such as Exxon Mobil, Shell, or BP.

The environmental protection organization Mighty Earth blamed Cargill and its competitor Bunge for deforestation in the Bolivian Amazon and in Brazil. In the area of the Cerrados, the savannahs of central Brazil, an area of around 130,000 hectares was deforested between 2011 and 2015 because of Cargill.

This criticism is probably one of the reasons why the company has committed to more sustainable business practices. Since 2017, the Group has been one of almost 10,000 members of the UN Global Compact initiative, which is committed to making globalization more socially and environmentally friendly.

However, Mighty Earth recently published a detailed report on Cargill’s environmental misconduct in mid-July. According to the environmental organization, the company had several months to make changes, but failed to do so.

Cargill’s role in the global food business is ambivalent. As one of the largest agribusiness corporations worldwide, Cargill controls a significant portion of global supply chains. This market power enables the company to exert political influence and shape decisions in food policy. However, the question remains whether this influence is truly exercised in the best interests of the public or primarily serves the company’s own interests.

Mars Inc.

[official website of the company]

Mars Inc. is a U.S.-based multinational manufacturer of confectionery, pet food, and other food products, as well as a provider of pet care services, with a revenue of 45 billion USD in 2022. The U.S. business magazine Forbes ranked the company as the fourth-largest privately held company in the United States.

„As a global company with the footprint of a small country, we have the responsibility – and the opportunity – to leave a lasting impact on the world“, is the message from the co-organizer of the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise.

However, the lasting impact on the world has some downsides. The following can be found on Wikipedia in this regard:

2019 gab Mars bekannt, dass sie nicht garantieren können, dass ihre Schokoladenprodukte frei von Kindersklavenarbeit sind, da sie nur 24 % ihrer Einkäufe bis auf die Ebene der Farmen zurückverfolgen können. In 2019, Mars announced that they could not guarantee that their chocolate products were free from child slave labor, as they could trace only 24% of their purchasing back to the farm level.

In 2021, Mars was named in a class action lawsuit filed by eight former child slaves from Mali who alleged that the company aided and abetted their enslavement on cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast. The suit accused Mars (along with Nestlé, Cargill, Barry Callebaut, Olam International, the Hershey Company, and Mondelez International) of knowingly engaging in forced labor, and the plaintiffs sought damages for unjust enrichment, negligent supervision, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. In June 2021, the United States Supreme Court dismissed the lawsuit on the grounds that as the abuse had happened outside the United States, the group did not have standing to file such a lawsuit.

A CBS television news investigation in 2023 found children as young as five years old working in the Ghana supply chain of Mars to harvest cocoa for brands such as Snickers and M&Ms.

In September 2017, an investigation conducted by NGO Mighty Earth found that a large amount of the cocoa used in chocolate produced by Mars and other major chocolate companies was grown illegally in national parks and other protected areas in Ivory Coast and Ghana. The countries are the world’s two largest cocoa producers.

The report documents show, in several national parks and other protected areas, 90% or more of the land mass has been converted to cocoa. Less than four percent of Ivory Coast remains densely forested, and the chocolate companies‘ laissez-faire approach to sourcing has driven extensive deforestation in Ghana as well. In Ivory Coast, deforestation has pushed chimpanzees into just a few small pockets, and reduced the country’s elephant population from several hundred thousand to about 200–400.

Mars Inc., as one of the largest global food companies, positions itself as a responsible player with the aim of having a sustainable impact on the world. However, the publicly available information paints a rather ambivalent picture and suggests that Mars Inc. may base its strategic decisions more on its own interests and market needs than on long-term social and environmental goals.

1.2. The Participants

Who were the participants in the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise?

The event was primarily aimed at high-ranking officials and experts from Brazil, continental Africa, China, the European Union (EU), India and the USA, as well as multilateral institutions, companies and investors.

However, anyone looking for representatives of small and medium-sized agricultural businesses in the list of participants will be disappointed. Instead, you will find the following organisations, among others:

Embrapa (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária)

[official website of the organization]

Embrapa is the Brazilian Agricultural Research and Development Organization, which plays a central role in the development and modernization of agriculture in Brazil. The organization is part of the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture. Its mission is to develop technologies through innovative research that increase agricultural productivity, minimize environmental impacts, and improve food security.

Embrapa conducts a wide range of research projects and has played a crucial role in optimizing crops. The organization develops varieties specifically tailored to Brazil’s climatic conditions and promotes the use of modern farming methods. These advancements have transformed Brazil from a net importer to one of the leading agricultural producers and exporters in the world.

At the same time, Embrapa also faces criticism, particularly with regard to its environmental and social impact resulting from the promotion of intensive industrial agricultural practices.

Embrapa has played a key role in the expansion of genetically modified monocultures such as soy, corn, and sugarcane in Brazil. Critics view the promotion of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) as a threat to the environment and the food sovereignty of farmers. These monocultures have led to a range of environmental issues, including deforestation, soil degradation, and the loss of biodiversity.

The intensive agriculture promoted by Embrapa often relies on the use of agrochemicals and artificial irrigation, which can lead to the overuse of water resources and the contamination of soil and water with pesticides and fertilizers.

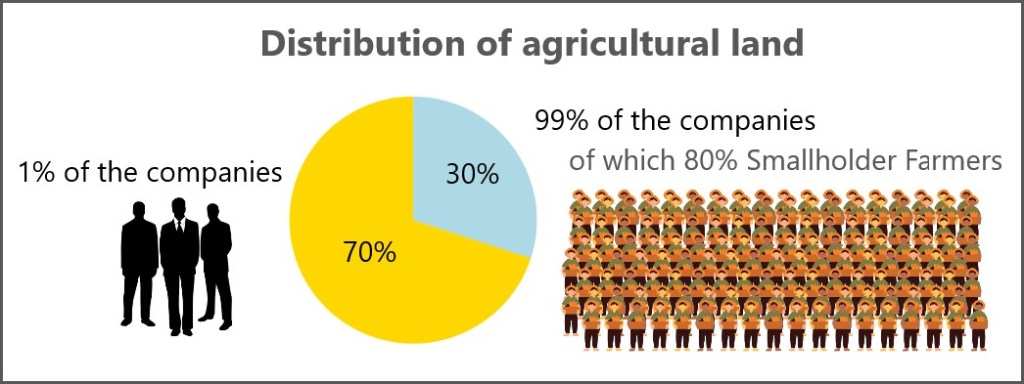

Critics accuse Embrapa of prioritizing the interests of large agribusinesses over those of small farmers. The expansion of industrial agriculture has often led to the displacement of small farmers and indigenous communities. The technologies promoted by Embrapa have frequently strengthened large landowners, resulting in a greater concentration of land in the hands of a few. This has exacerbated social inequalities and undermined the livelihoods of many small farmers.

In an analysis titled „Shallow fixes and deep reasonings: framing sustainability at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa)” from December 2023, the authors reach the following conclusion: „Our results show that while Embrapa promotes practices based on alternative approaches such as agroecology, its deeper framing often reflects the core assumptions driving dominant industrial food systems. This framing reinforces underlying logics of control, efficiency, and competition aligned with the productivist paradigm and excludes divergent perspectives that exist within the organization.“

Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC)

[official website of the company]

LDC is one of the oldest and largest agribusiness companies in the world. The company is a key player in the global trade of agricultural commodities and is part of the so-called „ABCD” companies (Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus), which dominate the global agricultural market. The firm operates globally and is primarily engaged in the trading, processing, and transportation of agricultural raw materials. It also operates a variety of infrastructure, such as warehouses, processing plants, and transport fleets, to support the trade of these commodities.

In December 2022, Peruvian and international organisations filed a complaint with the OECD in the Netherlands calling for the Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) to be held accountable for contributing to negative impacts on the environment, human rights and corruption through the sourcing of palm oil from the Ucayali region in the Peruvian Amazon. In September 2023, the OECD supervisory authority admitted the complaint filed by the indigenous organisations against Louis Dreyfus Company.

Further criticism of LDC’s business practices can be found in this article.

Kellogg Company

[official website of the company]

The Kellogg Company (also known as Kellogg’s) is a leading multinational food company, primarily known for its breakfast products such as cornflakes, cereals, and snacks. Over the years, Kellogg’s has grown into one of the largest producers of processed foods globally and is currently operating in over 180 countries.

Kellogg’s products, particularly its breakfast cereals, have often been criticized for their high sugar and salt content. Despite efforts to offer healthier products, the company has been accused of contributing to the obesity epidemic, particularly among children, with many of its flagship products. In April 2024, the particularly harmful aromatic mineral oil hydrocarbons (MOAH) and pesticide residues were detected in Kellogg’s cornflakes in laboratory tests. When Kellogg’s CEO recommended its muesli as an evening snack to poor families, the SPIEGEL magazine got upset in February 2024:

„The idea might not sit well with many: Multimillionaire Gary Pilnick has touted his cereals as the ideal solution for families on a tight budget. Mocking reactions were quick to follow.“

Global Crop Diversity Trust

[official website of the organization]

Crop Trust is an international organization dedicated to the conservation of plant genetic resources. Its main objective is to preserve the diversity of crops worldwide in order to ensure future food security. It was founded in 2004 by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) as an independent fund under international law. The foundation’s assets are provided by public and private donors. The list of donors includes names such as Bezos Earth Fund, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, DuPont/Pioneer Hi-Bred, Pepsico, Rockefeller Foundation, Syngenta and Unilever.

Crop Trust is known for managing the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, a secure seed bank that serves as a global backup for national and international gene banks. Preserving the genetic diversity of crops aims to help ensure global food security by providing farmers with access to a wide range of crop varieties adapted to different environmental conditions.

Some experts favor in-situ conservation (preservation of plants in their natural habitats) over ex-situ conservation (preservation outside their natural habitats, such as in gene banks) because the former promotes natural evolution and adaptation of plants. Critics argue that funding from large corporations and foundations could lead to these donors influencing the organization’s priorities and strategies. Concerns have also been raised about the unequal distribution of availability and access to genetic resources stored in gene banks, potentially disadvantaging small-scale farmers or less developed countries.

adelphi

[official website of the think tank and consulting organization]

adelphi is an independent German think tank and consulting organization specializing in sustainability, climate and environmental policy, and international development cooperation. Founded in 2001 and headquartered in Berlin, the organization operates in both the public and private sectors, offering research, consulting, and project implementation across various domains, including climate change, energy policy, water management, biodiversity, and sustainable economic development.

On the adelphi website, the following can be found:

„We are visionaries, designers, strategists and agenda-setters and work with and for governments, international organizations, cities, associations, NGOs and companies.“

But how independent is the „independent think tank” adelphi really?

Alexander Carius is a political scientist and founder and director of adelphi. Together with Harald Welzer and Andre Wilkens, he initiated the nationwide debate series „The Open Society – What Kind of Country Do We Want to Be?” in autumn 2015.

Andre Wilkens is also a political scientist who lived for many years in Brussels, London, Turin and Geneva, where he worked for the EU, foundations and the UN. Until 2015, he headed the Mercator Foundation’s Berlin Project Centre. Prior to that, he headed the Open Society Institute (OSI) of the Soros Foundation in Brussels and coordinated the activities of billionaire George Soros in Europe.

The adelphi study „Convenient Truths – Mapping climate agendas of right-wing populist parties in Europe” published in 2019 also raises a number of questions regarding funding. When asked about this topic, adelphi provides a contradictory answer:

„adelphi’s work is project-financed; there is no project-independent funding from external bodies. The study »Convenient Truths – Mapping climate agendas of right-wing populist parties in Europe« was financed from own funds.“

As a consulting organization, adelphi is heavily reliant on projects and contracts, often funded by governments and international organizations. This dependence could lead the organization to be less willing to take controversial or uncomfortable positions that might jeopardize its funding.

1.3. The Exercise

The „Food Chain Reaction” exercise was a strategic initiative carried out by a public-private partnership to sensitize government authorities and decision-makers from various sectors to the challenges and complex dynamics of a global food crisis through a specifically prepared simulation.

The exercise was based on several hypothetical scenarios for the period 2020-2030, which included extreme weather events, crop failures, rising food prices, political instability, and migration. These scenarios were designed to simulate challenging conditions and force decision-makers to respond quickly and effectively. The goal was to raise the participants‘ awareness of the interconnections between climate change, food production, geopolitical stability, and economic factors.

The key details of this exercise are presented in a promotional video.

The participants from the USA, Brazil, China, India, Europe, and Africa – primarily from the leading countries in food production – were divided into six teams. The seventh team represented businesses and investors, while the eighth team represented multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, the United Nations, and non-governmental organizations.

In designing the extreme situation, the focus was specifically on the following stress vectors:

- Climate change and extreme weather events

- Political and economic instability

- Population growth and urbanisation

Nothing brings people together like a common enemy. Behind this saying lies the fact that in extreme situations, certain biopolitical governance techniques come to the forefront. In this context, care within a doctrine of solidarity plays a central role.

A team of „experts” assembled by the organizers of the exercise moderated and guided the discussions of the participants. This „intensive support” helped the participants more easily identify which solutions were effective and which were not.

Against this background, the results of the exercise appear as „inevitable”. They can be summarized as follows:

Global Governance

While it was initially emphasized that national solutions are more likely to fail, by the end of the exercise, the only good and right solution was reached: Global Governance! The exercise highlighted the importance of multisectoral approaches, where actors from different sectors (government, private sector, NGOs) must collaborate to find comprehensive solutions.

„Teams deepened their commitment to global and regional cooperation and collaboration during crisis periods, in large part due to players’ open acknowledgement that no one nation, organization, or business could adequately address global food security.“

A Global Carbon Tax

The development and implementation of policies addressing climate change played a crucial role in defining the appropriate solutions.

„The link between climate and food security was well recognized across the wide variety of global leaders who played the game. In addition, teams agreed to price environmental services, price carbon, support the development of a market for carbon trading, and cap global emissions levels.”

The New Normal is Volatility

„As the game advanced, teams confronted a »new normal« characterized to a large degree by volatility and uncertainty. Toward the end of the game, during the Global Summit on Climate Security and Vulnerability, representatives of each of the teams … came together to address security issues in the new, more volatile world. Key initiatives in the framework included:

Strengthening existing institutions and authorities under the United Nations…,

Creating a new Strategic Headquarters under the United Nations to better coordinate member states’ use of military and nonmilitary assets, and to preposition materials in areas of anticipated need.

A broad consensus developed around the need for timely, relevant, and credible global information on food security drivers and indicators. The final round of play culminated in the convening of a Global Summit on Climate Security and Vulnerability, during which representatives of all teams, … expressed the desire for a more robust global coordination mechanism, with greater capacity to respond to climate related conflict and food system volatility.”

1.4. Some Conclusions

The selection and prioritization of stress vectors such as climate change, political instability, and population growth initially directed the focus toward global and comprehensive crisis scenarios, making national solutions appear insufficient. This suggests a certain predetermined nature of the exercise outcomes, which left little room for alternative solutions at the national or local level.

Another point is the „intensive guidance” provided by a team of organizers and experts who directed and moderated the discussions. This structural framing may have significantly shaped the participants‘ perspectives and approaches to solutions, ensuring that the favored approach of Global Governance appeared „without alternative”.

In addition, the solution of global carbon pricing and emissions trading was emphasized, highlighting that the exercise also advocated for clearly defined economic and regulatory measures to be implemented at a global level.

The absence of small and medium-sized agricultural enterprises as direct participants in the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise is also notable, especially as they are key players in the agricultural sector in many regions of the world. The exercise focused mainly on the political and economic decisions made by government agencies, large companies and international organizations.

Instead of analyzing real events, the exercise used hypothetical scenarios to simulate the impacts of climate change, political instability, and economic factors on food supply. The focus was on developing policy measures and fostering international cooperation based on predefined narratives. An exercise based on simulated scenarios and primarily involving high-level stakeholders cannot fully account for the real-world conditions and challenges faced by farmers and local communities. Without the direct involvement of smaller stakeholders, crucial practical insights and needs that are essential for implementing strategies at the local level are overlooked.

This top-down approach to securing the global food supply creates an environment where small and medium-sized enterprises increasingly become dependent on a few global players. In practice, this manifests in various ways:

a) Technology and Innovation

Large companies invest heavily in the research and development of new agricultural technologies and methods. When it comes to accessing these innovations, small and medium-sized farmers are increasingly dependent on the offers and conditions dictated by large agricultural corporations.

b) Market Access and Distribution

Large companies control a significant portion of global food supply chains. In most cases, small and medium-sized farmers rely on these established distribution channels to bring their products to market, which increases their dependence on the major players.

c) Financial Support and Resources

Large corporations and financial institutions often provide the financial support and resources needed to modernize and scale agricultural production. This can put small and medium-sized players in a position where they need loans and investments from these large players. Such financial dependencies could limit farmers‘ freedom of choice in terms of farming methods, crop varieties and market access.

d) Regulations and Standards

Large companies often have the resources to fulfil and even help shape strict regulations and quality standards. Small and medium-sized companies have to adapt to these standards, which further increases their production costs and dependence on the large companies that set these standards.

In summary, the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise appears to have a strong preference for global, centralized solutions. The scenario and design of the exercise suggest a bias that gave less consideration to potential national or decentralized approaches, raising questions about the objectivity of the exercise.

1.5. From Simulation to Reality

„The best way to predict the future is to invent it.“

Alan Curtis Kay – American computer scientist

The „Food Chain Reaction” exercise simulated a global food crisis resulting from a combination of climatic, economic and geopolitical factors for the period from 2020 to 2030. Although the exercise focussed on a climate catastrophe, many of the scenarios played out in the simulation can be transferred to actual events in the period from 2020 to 2024.

The era of volatility was ushered in in 2020. While in the simulation it is caused by climate change and extreme weather events in the period 2020-2022, in reality we experienced the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

„We face an impending global food emergency of unknown, but likely very large proportions. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the control and mitigation measures enforced worldwide, combined with the massive economic impacts of these necessary measures, are the proximate causes of this emergency. Conflict, natural disaster, and the arrival of pests and plagues on a transcontinental scale all preceded COVID-19 and serve as additional stresses in many contexts. But there are also deep structural problems in the way our food systems function, which we can no longer ignore.“

is stated in the UN document „The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition“ from June 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic had far-reaching impacts on global food supply chains from 2020 to 2022. One of the most significant consequences was the disruption of supply chains. Lockdowns, border closures, and quarantine measures led to logistical challenges worldwide, severely affecting the transportation of food and agricultural products. This caused delays, shortages, and significant price fluctuations. Additionally, farmers in many countries faced an acute labor shortage as COVID-19-related restrictions severely limited access to seasonal workers. These workers were essential for the harvesting and processing of food.

The economic impacts of the pandemic drove food prices up, especially in countries with low domestic production. In some countries, there were also supply shortages of imported food. Millions of people, particularly in developing countries, lost their sources of income and could no longer afford basic food items. Agricultural production also suffered due to the effects of the pandemic. Production losses were caused by labor shortages, disrupted supply chains, and limited access to resources such as seeds and fertilizers.

Small farmers, especially in developing regions, who often come from economically precarious backgrounds, were the main victims of this crisis. The collapse in trade, the closure of village markets and domestic travel restrictions posed a real threat to their livelihoods.

„To assist smallholder farmers in Asia, Africa and Latin America who are facing additional challenges resulting from COVID-19, Bayer, as part of its societal engagement activities and through its new „Better Farms, Better Lives” initiative, is providing seeds and crop protection inputs as well as assistance with market access and support for health and safety needs.

Bayer is committed to helping more than 100 million smallholders in low- and middle-income countries by 2030. The immediate COVID-19 response through the „Better Farms, Better Lives” initiative complements on-going smallholder support which will aid in mid-term recovery as well as long-term resilience. Additionally, in collaboration with others and to ensure the greatest successful impact for smallholders, Bayer will work and expand its partnerships with governments, internationally recognized NGOs and local organizations; create a Smallholder Center of Excellence for sharing successes; provide accelerated access to digital farming tools to increase capabilities; scale up existing and new value chain partnerships and further expand value chain partnerships across Asia-Pacific countries.”

is stated in Bayer AG’s press release from June 17, 2020.

This noble gesture is a practical demonstration of how smallholders and governments are increasingly becoming dependent on a few global players through partnerships. Bayer’s contribution titled „Can Food Supply Chains Cope with COVID-19?” from May 2024 contains further clear statements in this regard:

„We cannot go back to local-only food chains. We are living in a global food system. We must develop intelligent global food systems which are sustainable, circular and inclusive for smallholder farmers.

One solution to help achieve this is the greater use of technology and data. This pandemic is going to have long-term effects on every part of our world. There will be greater use of technology, such as robotics in picking products, warehouses and cold storage areas.

We will be collecting more at every point to gather information as food goes through the supply chain. The more data we have, the more accurate models and better forecasting we can make.

Due to COVID-19 we are going to rethink our current food systems. This offers opportunities for transitions, making our current systems more resilient and sustainable, and global systems more intelligent. To make this happen, strong and effective collaborations between academia and the private and public sectors are needed.“

Whether these statements can be interpreted as „Resistance is futile. You will be assimilated” depends on how the inevitable adaptation of traditionally local and less technology-intensive smallholders to these new standards takes place. The key question is how this integration is designed – whether it respects the autonomy and traditional knowledge of the smallholders, or if it indeed appears to be a forced adaptation. The near future will reveal the answer.

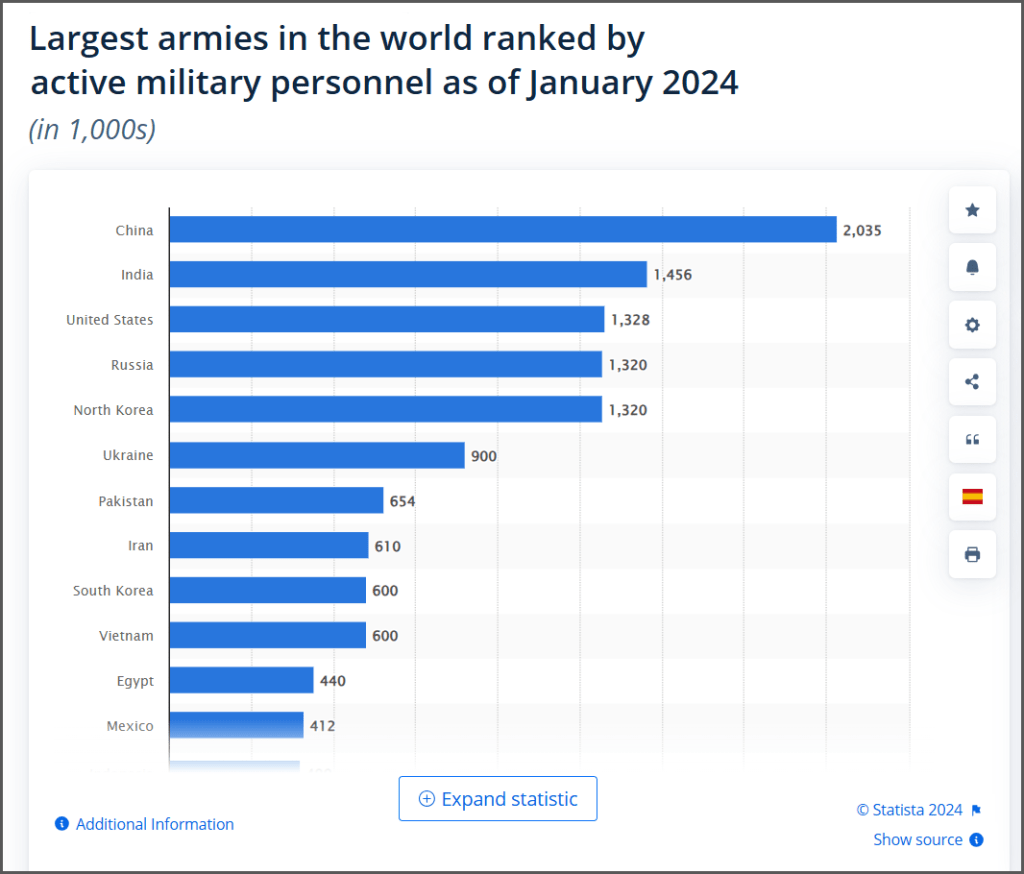

Between 2022 and 2024, the food crisis continues to escalate in the Food-Chain-Reaction simulation. Key drivers of the crisis include a drastic increase in oil prices, growing unrest, rising migration, further increases in food prices, as well as heat stress in Russia and Ukraine, which reduces grain reserves.

In the real world, the controversial debate about the future geopolitical alignment of Ukraine escalated in February 2022 into an open armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine, with the EU and NATO indirectly involved.

The war between Russia and Ukraine has had significant impacts on global food supply since 2022. Both countries are major exporters of wheat, corn, and sunflower oil, and before the war, they together accounted for nearly a third of global wheat exports. Due to the military conflict and blockades in the Black Sea, these exports were severely disrupted, particularly during 2022-2023, leading to a global shortage of grain. Regions like the Middle East and North Africa, which are heavily dependent on imports, felt the effects in the form of rising prices and increased food insecurity.

The shortage of grain has led to a sharp rise in food prices worldwide, which has hit low-income households particularly hard. In addition, the war has placed a heavy burden on the fertilizer market, as Russia is a major exporter of fertilizers and their components. The sanctions against Russia and the resulting supply chain disruptions led to higher fertilizer prices, forcing many farmers to use less fertilizer, reducing crop yields and further exacerbating the global food crisis.

The crisis has also had far-reaching political and economic consequences. Sanctions against Russia and trade restrictions have further strained global supply chains for agricultural products and financial flows. Many countries, particularly developing nations that rely on imports from Russia and Ukraine, are now grappling with food insecurity and social unrest. In some regions, this has led to humanitarian emergencies.

The war in Ukraine continued to contribute to an increase in prices and supply bottlenecks for important energy sources such as gas and fuels (petrol, diesel). This resulted in noticeable additional costs for farmers and companies in the food industry. As a result, producer prices for agricultural products rose significantly, particularly in Europe. Together with the negative impact on consumer sentiment caused by record inflation, the pressure on companies in the agricultural sector increased considerably.

As a result of this development, the EU extended the crisis aid for farmers in May 2024. The temporary crisis framework had originally been introduced two years ago after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The financial support measures aim to cover the additional costs for energy and fertilizers that farmers have incurred due to the crisis. While these government aids provide valuable support to farmers during acute crises, their long-term provision could lead to a dependency on state assistance. If farmers are repeatedly reliant on subsidies to survive economically, this could impair their ability to operate independently of state interventions. In this context, the Tagesschau reported as follows in December 2022:

„At 450 billion euros, agricultural subsidies are the largest item in the EU budget.

Every year, the European Commission distributes more than 50 billion euros in agricultural subsidies. Germany benefits the most after France and Spain. More than 400,000 recipients in Germany have received a good 53 billion euros since 2014. German farmers have received an average of 127,000 euros over the past eight years. But the gap is wide: the top one per cent of recipients received almost a quarter of all subsidies – in other words, more than twelve billion euros or just under 30,000 euros per farm per month. In contrast, the entire bottom half of small farms and farmers together received less than four billion euros. That is just 200 euros per farm per month.

The problematic trends are evident throughout Europe. In the eight countries analysed, the main beneficiaries of subsidies are large companies and public institutions. In all countries, a few large recipients receive the most money. The distribution is often even more unequal than in Germany. The top one per cent of recipients in Europe collect more than a third of all subsidies.”

The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the economic situation of many EU farmers and further increased their dependence on state aid. This development could lead to the agriculture sector becoming even more integrated into state support mechanisms in the long term. Government programs and subsidies may be tied to conditions that force farmers to adopt certain technologies or practices, making it easier for governments to enforce their agricultural policy goals.

In times of crisis, such as during the Ukraine war, acceptance of state intervention and the narratives associated with it tends to increase. These circumstances provide an opportunity to position the transition to „greener” agriculture or the introduction of new technologies as necessary developments. Critical voices against such narratives are often seen as unproductive or obstructive to the common good in this context. However, in the long term, an increased reliance on state subsidies could limit farmers‘ flexibility and hinder their ability and willingness to pursue independent alternatives.

This dynamic makes it easier for governments to enforce agricultural strategies and narratives, making the implementation of top-down approaches in agriculture, as practiced during the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise, almost inevitable.

2. The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Shaping Food Systems

The „Food Chain Reaction” exercise modeled a series of crisis events that threatened the stability of the global food system, rapidly leading to food shortages, price increases, and political unrest in an interconnected world. The main goal was to raise awareness among high-level actors in politics and business about solutions in the field of global governance.

In this context, the World Economic Forum (WEF) published the report „Innovation with a Purpose: The role of technology innovation in accelerating food systems transformation” in 2018, in collaboration with the consulting firm McKinsey. The report builds on insights and scenarios from the „Food Chain Reaction” exercise and proposes specific technological and policy measures that could fundamentally transform the global food system.

The document emphasizes the central role of technology and innovation in reshaping global food systems to address pressing challenges such as food insecurity, climate change, and the promotion of sustainable development. In particular, the rapid population growth in urban areas increases the demand for food and alters consumption patterns, putting pressure on agricultural resources and further amplifying existing inefficiencies in production and distribution.

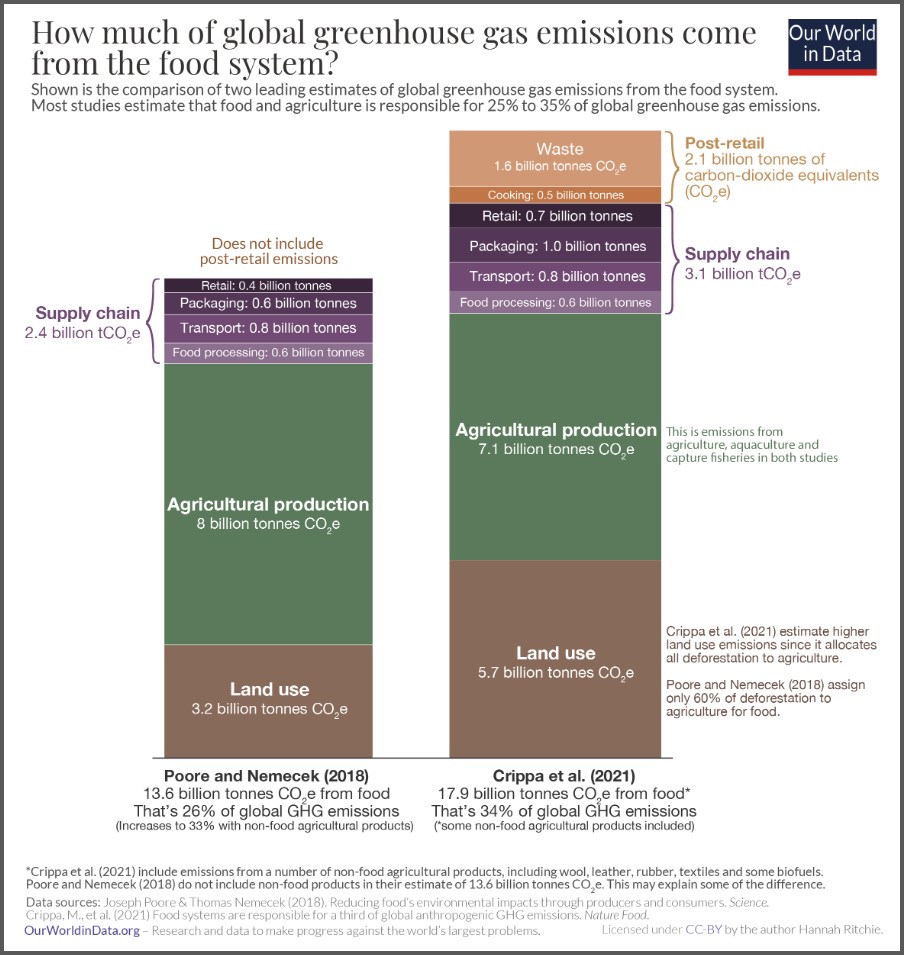

The authors describe agriculture as a sector with dual responsibility: on the one hand, it significantly contributes to climate change, and on the other, it is heavily impacted by its consequences, including soil erosion, water scarcity, and the loss of biodiversity. These issues exacerbate food insecurity and malnutrition, which persist despite global progress. Additionally, significant losses along the value chain are highlighted, further amplifying the unequal distribution of resources.

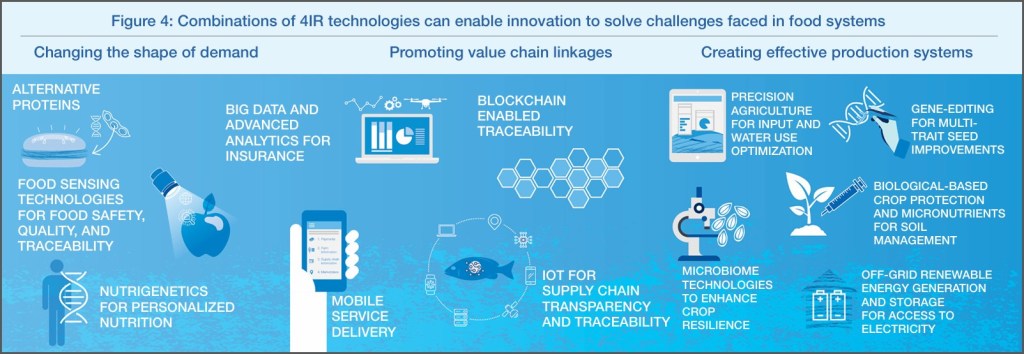

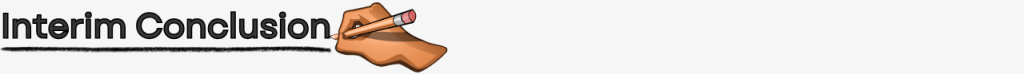

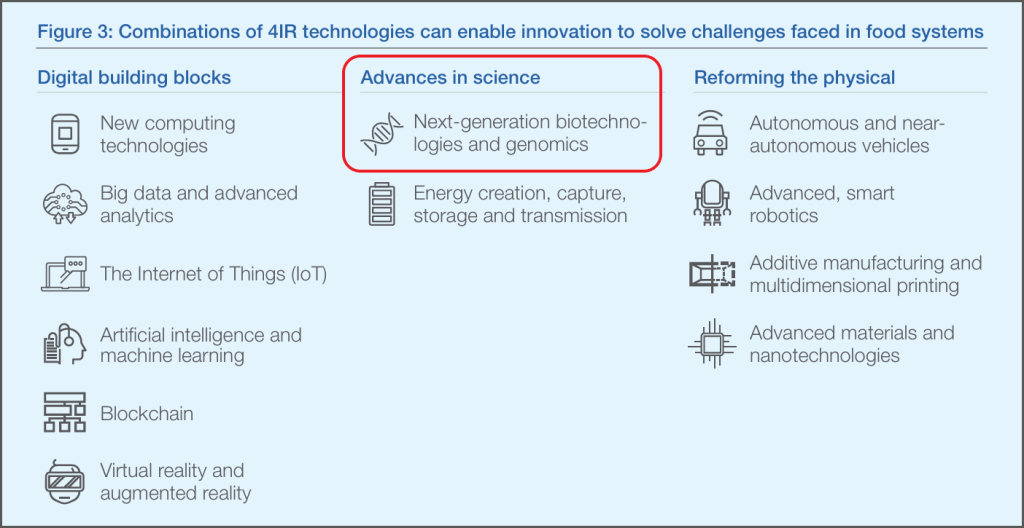

Innovative technologies are highlighted as crucial solutions. It is emphasized that digital approaches such as Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things (IoT) can help make agricultural processes more efficient, optimize resource use, and enable data-based decisions in real time. Advances in biotechnology, particularly through techniques like CRISPR-Cas9 for precise DNA modification, also offer new possibilities for developing more resilient plant and animal species that are better adapted to diseases and climate change. These developments make significant contributions to sustainable growth and a future-proof agricultural sector.

Additionally, the authors point out that innovative production methods such as vertical farming, lab-grown meat, and alternative protein sources (e.g., insects) could offer promising opportunities to make food production more sustainable and resource-efficient. Blockchain technology is also described as a potentially powerful tool to enhance transparency and traceability in global supply chains. This could not only reduce fraud and contamination but also strengthen consumer trust in the origin and quality of food products.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) is an influential global organization and provides an important platform for the exchange of ideas and strategies between political, economic and social leaders. It plays a central role in shaping global agendas. Through reports, studies and initiatives, the WEF addresses important topics such as climate change, digitalization, social inequality and the future of work. Many governments and companies align their policies and strategies with the recommendations and discussions initiated by the WEF.

The WEF also promotes collaboration between governments and the private sector. These partnerships significantly influence policy decisions and economic developments. Given this far-reaching impact, it is worthwhile to closely examine some of the solutions proposed in the aforementioned WEF report.

2.1. Changing Demand

a) Alternative Proteins

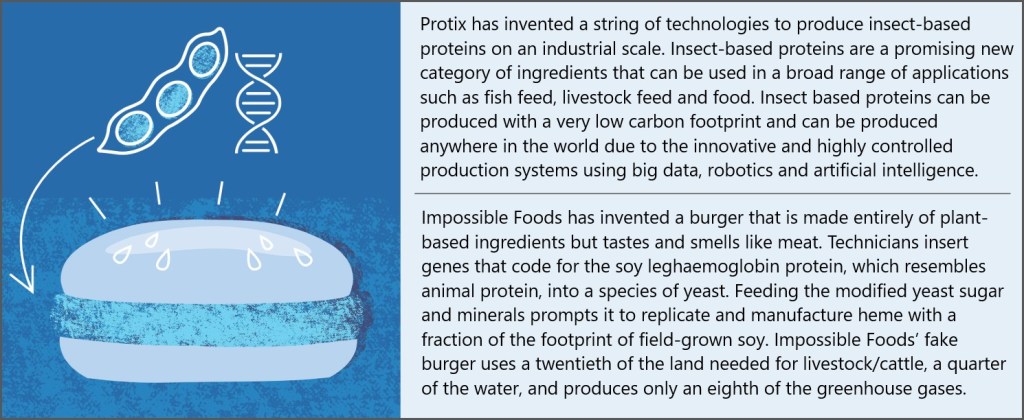

The authors of the report emphasize that an adequate supply of protein is essential for a healthy diet. With the global population growing to almost 9 billion people and changing eating habits due to increasing prosperity and urbanization, the demand for animal protein is increasing worldwide. Although this development could improve the nutritional situation of underserved people, it brings with it considerable environmental problems. As the report points out, „livestock today account for 15% of greenhouse gas emissions, consume 10% of the world’s fresh water and use more than one quarter of the planet’s ice-free surface”.

To address these challenges, the WEF considers the supply of safe, affordable, and sustainably produced protein sources to be crucial for the future. Alternative proteins from more environmentally friendly sources such as insects, plants, aquaculture, and cell cultures could represent promising alternatives to conventional proteins for both human and animal consumption.

To ensure consumer acceptance of these alternative protein sources, the report recommends combining national media campaigns and public awareness initiatives with targeted regulations and financial incentives. Additionally, technological advancements should guarantee that such products are at least equivalent in terms of nutritional value, taste, and texture, while being offered at competitive prices.

No sooner said than done: „Plant-based protein sources will become increasingly important for a plant-centred diet. The German government will examine measures to effectively support this development.“ … „Although sales of alternatives to animal-based foods have increased in recent years, they are still at a relatively low level. Promoting innovation for producers could lower barriers to market entry, increase competition and ultimately lead to lower prices for consumers. In addition, supporting the matching of growers and processors can also make an important contribution. Both aspects are addressed in the BMEL’s announcement on alternative protein sources for human nutrition“, can be read in the current nutrition strategy paper (pages 23 and 25) of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL).

European agriculture ministers are currently deeply engaged in discussions about how to introduce „novel foods” without losing sight of „culinary tradition” – a topic that is sparking intense debate. The term „novel foods” is broad and encompasses various types of products, including edible insects and vegetarian alternatives to dairy and meat products. According to the European Commission, the consumption of vegetarian alternatives to meat, dairy, and seafood has quintupled since 2011 and is expected to continue rising. The EU has so far approved the sale of four insect species, with at least eight more applications currently under review. On July 26, 2024, the first EU application for the sale of lab-grown meat was submitted.

While discussions among EU agriculture ministers about „novel foods” remain controversial, many of the leading agricultural and food producers in the EU believe that innovations and traditions can coexist. They are convinced that new food options do not necessarily threaten the culinary culture of the EU. Italian Agriculture Minister Francesco Lollobrigida, who has reaffirmed his opposition to lab-grown meat, succinctly describes the dilemma facing EU politicians: „I don’t actually see the desire to slow down any process, but to know in which direction it is going.”

The direction in which it is heading is clearly outlined in the Official Journal of the European Union of January 3, 2023:

„(7) In its scientific opinion, the Authority concluded that Acheta domesticus (house cricket) partially defatted powder is safe under the proposed conditions of use and use levels. Therefore, that scientific opinion gives sufficient grounds to establish that Acheta domesticus (house cricket) partially defatted powder when used in multigrain bread and rolls, crackers and breadsticks, cereal bars, dry pre-mixes for baked products, biscuits, dry stuffed and non-stuffed pasta-based products, sauces, processed potato products, legume- and vegetable- based dishes, pizza, pasta-based products, whey powder, meat analogues, soups and soup concentrates or powders, maize flour-based snacks, beer-like beverages, chocolate confectionary, nuts and oilseeds, snacks other than chips, and meat preparations, intended for the general population, fulfils the conditions for its placing on the market in accordance with Article 12(1) of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283.”

In its report, the authority also states that these novel foods contain proteins that can potentially trigger allergies. Although the authority does not yet have any clear evidence of serious allergic reactions, the possibility that consumption could trigger allergies is pointed out.

The potential risk has been known for years. In a scientific article from 2018 titled „The house cricket (Acheta domesticus) as a novel food: a risk profile”, an international research team emphasizes that crickets can cause allergic reactions in certain individuals. This is due to the fact that crickets and other arthropods, such as shrimp, crabs, and lobsters, contain similar proteins. These proteins can trigger similar reactions in people with allergies. As insect consumption is expected to increase worldwide, there could also be an increase in allergic reactions to these insect species.

In addition, crickets also contain specific allergens such as hexamerin B1, the allergenic potential of which is not yet fully understood. To avoid health risks, crickets and products made from crickets should be clearly labelled in shops. It is important to realise that scientific findings that apply to one insect species are not automatically transferable to related species. Therefore, a separate risk assessment should be carried out for each commercially farmed insect species.

As more products with edible insects enter the market, it is likely that new allergens associated with crickets and other edible insects will be discovered. Additionally, the development of new processing techniques for insect products could introduce new chemical or microbial hazards.

New insights on this topic are provided by the recent analysis „The Allergen Profile of Two Edible Insect Species – Acheta domesticus and Hermetia illucens”. The study has identified several allergens in insects that could cause problems for allergy sufferers, especially those who are already allergic to crustaceans. Additional proteins were also discovered that could trigger allergic reactions but have not yet been compared with known crustacean allergens. These new allergens need to be studied further to understand how they affect the body and how to better diagnose and treat them.

The scientists have also shown that standard allergen test kits for crustaceans cannot be used to test insect products for allergens. Therefore, in future, the labelling of foods containing insects should ensure that these specific allergens are taken into account to avoid unwanted allergic reactions. This is particularly important because in some regions of the world up to 4% of people are allergic to crustaceans.

Critics view the EU Commission’s decision as an attempt to present the consumption of Acheta domesticus as safe despite potential health risks, in order to promote a more diverse diet and the introduction of sustainable protein sources. Supporters, on the other hand, argue that the potential benefits, such as access to sustainable protein sources, could outweigh the risks. However, this does not mean that the risks are being ignored; rather, they are considered acceptable as long as the prescribed safety measures are followed. Whether the saying „The end justifies the means” applies in this case depends on whether one is personally affected by the acceptable risks.

The health risks for the global population are at the top of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) agenda. The video message from the WHO Director-General, „Our food systems are harming the health of people and the planet”, illustrates the WHO’s perspective on food systems:

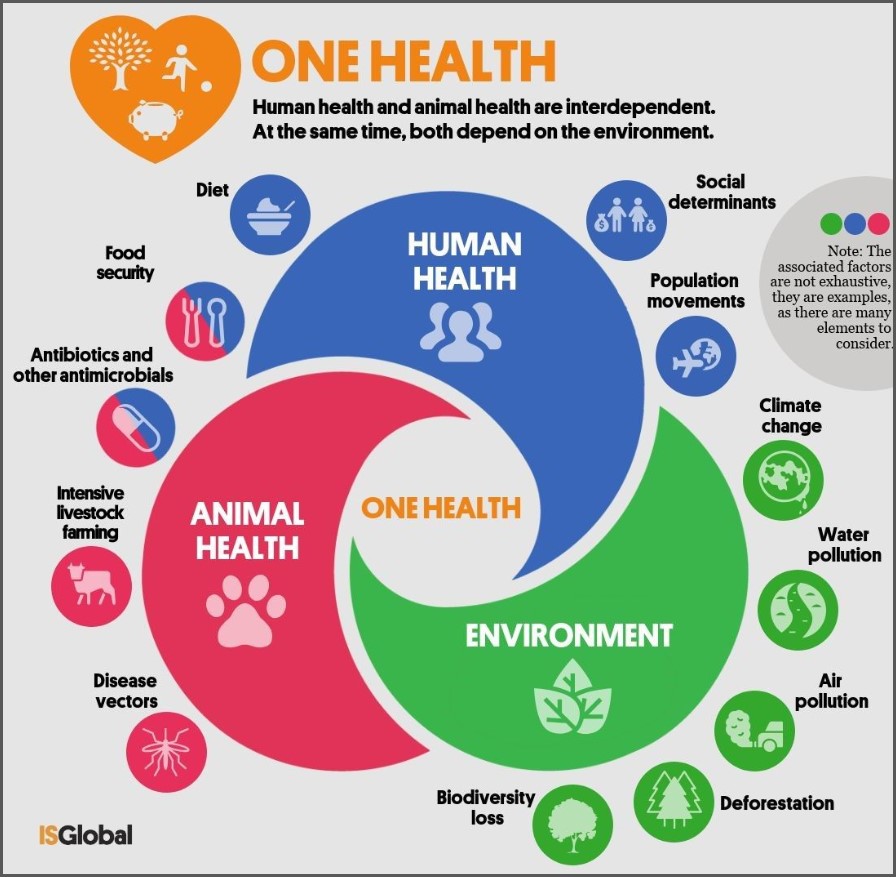

b) Inseparable Connection between the Health of People, Animals, and the Environment

According to the WHO, population growth and the increasing proximity of humans to wild and domestic animals are increasing the risk of diseases being transmitted from animals to humans. According to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), around 60% of known infectious diseases in humans are of zoonotic origin, as are 75% of the pathogens that cause emerging diseases. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) also points out that intensive livestock farming contributes significantly to environmental pollution. It causes more greenhouse gas emissions than global transport and exacerbates problems such as deforestation, high water consumption and soil contamination.

In addition, the excessive use of antibiotics and the occurrence of zoonoses increase health risks for humans. Deforestation deprives animals of their natural habitats and brings them closer to human settlements, further increasing the risk of zoonotic transmission. Furthermore, global travel and international trade facilitate the rapid spread of diseases across borders, meaning that an outbreak in one country can quickly have worldwide implications.

This inseparable connection between the health of humans, animals, and the environment is embodied in the WHO’s One Health approach, which changes the way governments, organizations, and institutions address and respond to health issues.

The One Health Approach and Its Impact on Agricultural Operations

The One Health approach is more comprehensive than the measures taken to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and emphasizes intersectoral collaboration at both the national and international levels. It requires coordinated governance structures that involve various sectors such as healthcare, veterinary medicine, agriculture, food production, and environmental protection to enable effective collaboration between authorities and organizations.

A central feature is the preventive focus, which directs resources and strategies towards early warning systems and the monitoring of animal and environmental health. By harmonizing international guidelines, the approach aims to ensure consistent and effective implementation. It emphasizes the importance of modern technologies and data analytics for monitoring and prevention, in order to detect potential risks at an early stage.

One Health promotes integrated governance, replacing reactive crisis management with preventive measures. This perspective provides policymakers with tools to address health crises in a holistic manner and, when necessary, implement targeted emergency measures.

The impact of the One Health approach on agricultural enterprises is profound. To avoid emergency measures, which often lead to financial ruin, farmers are forced to invest in infrastructure, veterinary measures, monitoring technologies, and training. This shift to One Health-compliant practices can be structurally and financially burdensome, especially for smaller farms. Access to funding and subsidies is crucial to manage this burden. However, this leads to an increasing dependence on external private or state actors, further limiting the independence of farmers. Furthermore, the dynamic adaptation to health and environmental requirements could increase pressure on agricultural enterprises and impair their competitiveness. A sudden change in regulations to combat animal diseases, such as African swine fever or avian influenza, could result in additional requirements for animal husbandry, hygiene, or vaccinations, forcing farms to quickly make new investments or adjustments. This continuous adaptation process could limit the independence of farms, making their operations more complex and costly. Additionally, it could lead to an increased dependence on external state actors and create the need to continuously allocate resources for the implementation of new regulations.

„Transforming food systems is therefore essential, by shifting towards healthier, diversified, and more plant-based diets”, is the WHO’s motto. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is one of the largest donors to the WHO.

c) Synthetic Foods

How Bill Gates envisions the transformation of food systems is outlined in detail on his blog, GatesNotes, as follows:

„Our plan can’t be to simply hope that people give up foods they crave. After all, humans are wired to want animal fats for a reason – because they’re the most nutrient-rich and calorie-dense macronutrient – in the same way we’re wired to crave sugar for an instant energy kick. What we need are new ways of generating the same fat molecules found in animal products, but without greenhouse gas emissions, animal suffering, or dangerous chemicals. And they have to be affordable for everyone.“

Savor, a start-up supported by Gates, summarizes what these new approaches could look like in concrete terms.

„Can’t we just eat the fossil fuels?“

„The thought that shifting humans from eating animals and plants to eating fossil fuels could enable the reclamation of all of those lands – and the ensuing sequestration of vast amounts of atmospheric carbon – was powerful.“

„The fats we make at Savor can be produced from fossil fuels like natural gas or from captured CO2 and green hydrogen. We have our work cut out for us both technically – making high purity and high-performance fats – and commercially – learning how to share our products and technology with the world in a way that addresses inevitable questions and concerns about safety and health.“

The following promotional video from Savor illustrates where the journey is heading:

Savor’s process enables the production of fats and other food components without traditional agricultural methods. Using CO₂ from the air and hydrogen from water, these elements are converted into fats through a thermochemical reaction. This approach represents an example of the next generation of „synthetic” foods, based on innovative processes.

A comprehensive overview of the broad spectrum of novel synthetic foods and the associated potential risk factors can be found here.

d) New Foods from the 3D Printer

Savor is not alone in its efforts to save the planet. The Austrian start-up Revo Foods has opened the „Taste Factory” in Vienna, a production facility for additive food manufacturing based on a specialized 3D printing process. With an impressive capacity of up to 60 tons per month, it is the largest facility of its kind in the world. „We are pushing the boundaries of food technology” is the company’s motto:

The comparison of 3D-printed food with the food replicator from the Star Trek universe might be tempting, but it is still technologically quite a distance away. In the February 23, 2024, episode of the SWR knowledge program „How Does Food Replication Work on Starship Enterprise?”, Dr. Hubert Zitt expressed a mix of enthusiasm and caution:

„But we are on a path with the production of food using 3D printers. Now, I don’t want to draw a direct comparison, but I do believe that in the future, we will increasingly produce food in this way. However, to be honest, I personally don’t wish for that. I love a good, juicy steak – if one is still allowed to say that today – and I don’t want to embrace the idea of having food artificially produced by some chemical companies.“

Handelsblatt provides an up-to-date overview of the top 50 out of 300 young companies headquartered in Germany that are positively changing the food industry or global nutrition. Further examples can be found here.

What may still seem like a mere idea to many today is only the beginning of a profound shift in the demand of the general population. However, this transformation process will develop gradually and will not take place abruptly, but rather step by step over the coming years.

Within the framework of public-private partnerships (PPPs), governments will gradually create political framework conditions that promote such innovations and at the same time support sustainable practices, for example through subsidies, tax incentives or regulatory adjustments.

The growing demand for alternative proteins and „novel foods” is likely to have negative consequences for the livelihoods of livestock farmers and for the economies of countries that are heavily dependent on livestock farming. The widespread introduction of such technologies could further destabilise traditional agricultural structures. Smaller farms in particular are likely to suffer from the increasing pressure of industrialization and technological upheaval, which could pose significant social and economic challenges.

The cultivation of plants for alternative proteins, such as soy or peas, could lead to the expansion of monocultures, which reduce biodiversity and increase the risk of soil degradation, pest infestations, and diseases. Although alternative proteins are generally considered more environmentally friendly, their production can still have negative environmental impacts if not conducted sustainably. For example, the intensive use of fertilizers and pesticides in the cultivation of protein crops or the high energy consumption in the production of lab-grown meat could have negative consequences.

As alternative proteins and synthetic foods are still relatively new, there are not yet sufficient long-term studies to fully understand their health effects over an extended period. Although chemically synthesized fats are structurally similar to conventional fats, small differences or impurities in the manufacturing process could have health consequences that may not be recognized until later. Many alternative proteins, especially in meat substitutes, are highly processed and often contain additives, stabilizers, salt, and fat. These ingredients can have long-term negative health effects, particularly when consumed in large quantities. Additionally, these proteins often lack important nutrients that naturally occur in animal products, such as vitamin B12, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids, which can lead to deficiencies without proper supplementation. Furthermore, certain alternative proteins carry an allergy risk. Soy or insect proteins can trigger allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, and novel proteins from algae or fungi could also cause unexpected allergies.

This shift in demand requires careful planning to minimize negative impacts on agriculture, rural communities, and human health. A crucial factor will be whether the responsible stakeholders address these risks seriously or accept them as unavoidable in order to accelerate progress. The balance between innovation and the protection of existing structures will ultimately determine the success of this transformation process.

2.2. Digitalization Across the Entire Value Chain

The authors of the WEF report paint a picture of an increasingly interconnected world, where the demand for more efficient, transparent, and traceable supply chains is growing. Consumers today not only want to know where their food comes from, but also want to be assured that it has been sourced in an ethical and sustainable manner. This is where various digital technology blocks come into play, which have the potential to fundamentally change the way we produce, transport, and consume food.

Agriculture and IoT

In the vision of the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Internet of Things (IoT) networks sensors and actuators that collect and exchange data on soil quality, plant condition and environmental conditions in real time. This technological development is revolutionizing agriculture. The data collected enables precise decisions to be made that use resources such as water, fertilizers and pesticides more efficiently, increase yields and minimize environmental impact at the same time. Technologies such as intelligent irrigation systems, GPS-controlled tractors, drones and advanced sensor technology are not only making agriculture more efficient, but also more sustainable, the authors of the study emphasize.

In the field of animal husbandry, digital technologies are aimed at improving animal welfare and health through continuous monitoring. Blockchain technologies can also ensure transparent traceability throughout the entire production chain. Additionally, satellite systems support the monitoring of ecologically valuable areas as well as compliance with biodiversity goals.

Supply Chain Management

In the food supply chain, IoT enables precise monitoring and tracking of each step – from harvest to delivery. Factors such as temperature and humidity during transport and storage can be specifically optimized to ensure the freshness and quality of products. This allows for efficient management of transportation routes, controlled handling of cold chains, and reduction of losses due to spoilage. Automated systems help reduce labor costs and optimize resource use, while real-time data improves planning and better coordinates supply and demand. Bottlenecks can be identified more quickly, and more accurate forecasts enable more efficient resource utilization.

Competitive Advantage and Future Perspectives

Investing in digital technologies increases productivity, reduces waste and cuts costs. These developments promote sustainability, efficiency and transparency while ensuring the competitiveness of farmers. The use of digital solutions not only improves current performance, but also secures the long-term future of agriculture – a central idea behind this strategic direction.

A true win-win situation for the environment, consumers, and businesses – at least in theory.

According to the Data Bridge Market Research report, the global market for IoT in agriculture will reach a volume of 32.71 billion US dollars by 2031, with an annual growth rate of 10.1%.

Technological progress and increasing competitive pressure are accelerating the transformation of agriculture, further reinforced by government subsidies and regulatory requirements. A key trend is the growing legal pressure to implement digital technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and precision agriculture. More and more governments are creating frameworks that promote these innovations in order to ensure high standards in environmental protection, animal welfare, and food safety.

Political Framework: CAP 2023-2027

The CAP 2023-2027 (Common Agricultural Policy) represents the latest reform of European agricultural policy, focusing on sustainable, environmentally friendly, and social standards. This policy, developed jointly by the EU Commission, Parliament, and Member States, aims to modernize European agricultural systems while ensuring the long-term competitiveness and stability of agricultural enterprises.

The CAP 2023-2027 introduces important innovations. A central component is the so-called Eco-Schemes, through which around 25% of direct payments to farmers are linked to environmentally friendly practices. These include measures for soil protection, promoting biodiversity, and sustainable water management.

Another important aspect is conditionality, which requires all farmers to comply with certain environmental and climate standards in order to remain eligible for funding. These include the preservation of permanent grassland and the protection of wetlands in order to protect valuable ecosystems. Social conditionality has also been newly introduced, which is aimed at safeguarding labor rights and fair working conditions in agriculture and thus represents a further step towards social sustainability.

This reform represents a significant change in financial support for the agricultural sector by restructuring the previous flat-rate direct payments in favour of environmental and social support criteria. While farmers previously received largely flat-rate direct payments, a significant proportion of this financial support is now linked to participation in environmentally friendly measures (eco-schemes) and compliance with certain standards (conditionality).

The CAP 2023-2027 sets clear requirements for environmental standards, sustainability and efficiency, which make the use of IoT and other digital systems almost indispensable. The automatic collection and reporting of relevant data simplifies compliance with CAP requirements and significantly reduces bureaucracy.

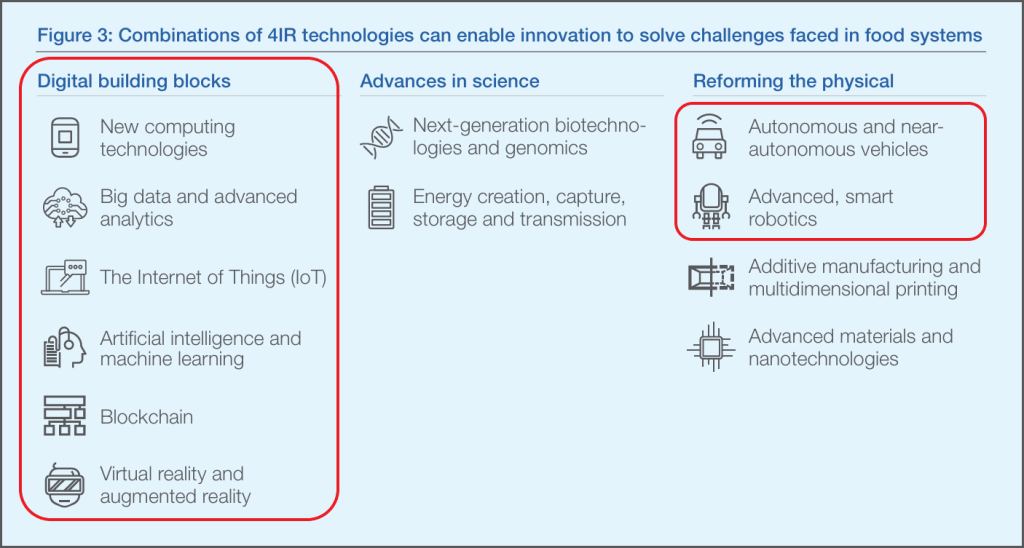

Experimental Fields

The practical application of various digital technologies is currently being explored and demonstrated on so-called experimental fields on farms in Germany.

Further information on this topic is provided in the promotional video „Climate, Weather, Harvest and Yield: What do Digital Experimental Fields in Agriculture achieve?” by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL):

In summary, the CAP 2023-2027 pursues ambitious environmental and sustainability goals that can be efficiently implemented through digital systems. This digital transformation proves to be a crucial factor for the future viability and competitiveness of the agricultural sector. Therefore, the CAP 2023-2027 can be seen as a political instrument for implementing the recommendations outlined in the WEF report „Innovation with a Purpose: The Role of Technology Innovation in Accelerating Food Systems Transformation”.

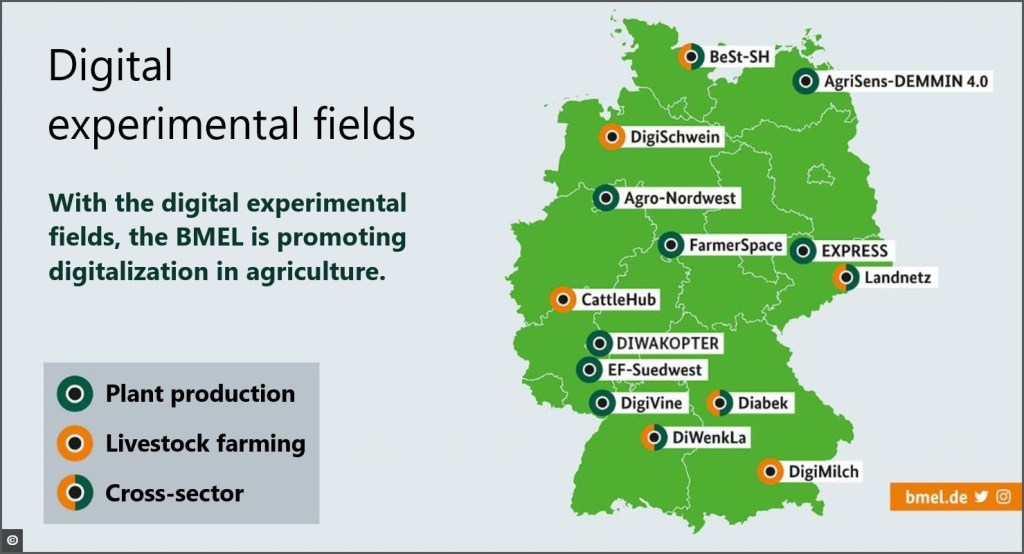

The analysis report „Digital Agriculture Market Size & Share Analysis – Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024 – 2029)” summarises the global development as follows:

The increasing awareness about the benefits of digital agriculture in optimizing agricultural production has resulted in a great boom in the agriculture market. With the growing food demand, owing to the increasing population, the adoption of digital agriculture tools is inevitable.

The United States is expected to invest a significant share in facilitating the ecosystem for future foods.