Life, in its incredible diversity and complexity, is the result of a fascinating interplay of countless biological processes and structures that often operate in the hidden. Every cell in our body, no matter how insignificant it may seem, is a small wonder of nature. It houses a multitude of proteins that, like tiny machines, tirelessly work to preserve life. These proteins not only ensure that our cells perform their daily tasks but also play a crucial role in protecting our bodies.

Our immune system, one of the most impressive creations of evolution, defends us against countless threats – from invading microorganisms to degenerated cells that can endanger our health. This defense system is a complex network of cells, proteins, and chemical signals that together make the difference between health and disease. In this essay, we will focus on this „wonderful world of life”, with a particular emphasis on the immune system. The goal of this work is to provide a comprehensive and accessible understanding of how the immune system functions. It is recommended to read the chapters in the given order so that the information builds upon itself step by step, allowing for a deeper understanding of the topic.

Let us now immerse ourselves in this marvellous world of life to understand how the invisible preserves our lives.

1. A Look Beneath the Skin – A Journey Within

2. The Cell – The Fundamental Building Block

3. Proteins – The Building Blocks of Life

4. From Code to Protein – Cellular Mechanisms

5. The Body’s Shield – Our Immune System

6. Hidden Defense – The Power of Cross-Immunity

7. Key takeaways

8. Closing words

Complete Table of Contents

1. A Look Beneath the Skin – A Journey Within

2. The Cell – The Fundamental Building Block

3. Proteins – The Building Blocks of Life

4. From Code to Protein – Cellular Mechanisms

4.1. From Signals to Actions

4.2. The Protein Biosynthesis

4.2.1. Transcription

4.2.2. Translation

4.3. The Protein

5. The Body’s Shield – Our Immune System

5.1. Origin of Immune Cells

5.2. Mechanisms of Immune Recognition: NON-SELF vs. SELF

5.2. a) SELF-Markers: MHC Molecules

5.2. b) SELF-Markers: CD47 Molecule

5.2. c) SELF-Markers: Sialic Acid

5.3. The Nonspecific Immune Defense

I – First Line of Defense: Mechanical and Chemical Barriers

II – Second Line of Defense: White Blood Cells

5.3. a) Granulocytes

5.3. b) Macrophages

5.3. c) Dendritic Cells

5.3. d) Natural Killer Cells

5.4. The Complement System

5.5. The Specific Immune Defense

5.5.1. Key Players of the Adaptive Immune Response

5.5.1. a) Development and Maturation of Lymphocytes

5.5.1. b) Humoral and Cellular Defense Mechanisms

5.5.1. c) Migration and Distribution of Lymphocytes

5.5.1. d) Structure of the Lymphatic Organs

5.5.2. Naive B and T Cells: The Diversity of the Immune Response

5.5.3. The Role of Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs)

5.5.3. a) Antigen Presentation via MHC-II Molecules

5.5.3. b) Antigen Presentation via MHC-I Molecules

5.5.3. c) Dendritic Cells Migrate to the Lymph Nodes

5.5.4. The Importance of Lymph Nodes for the Adaptive Immune Response

5.5.5. Recognition Phase

5.5.6. Activation Phase

5.5.6. a) T Cell Activation

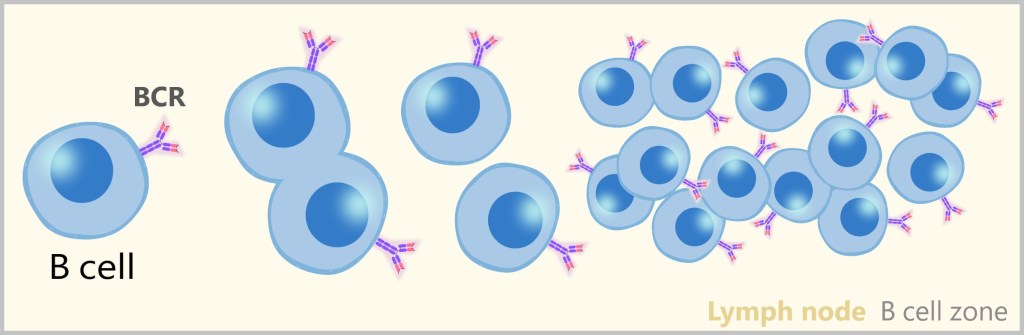

5.5.6. b) B Cell Activation

5.5.7. Effector Phase

5.5.7. a) T Helper Cells

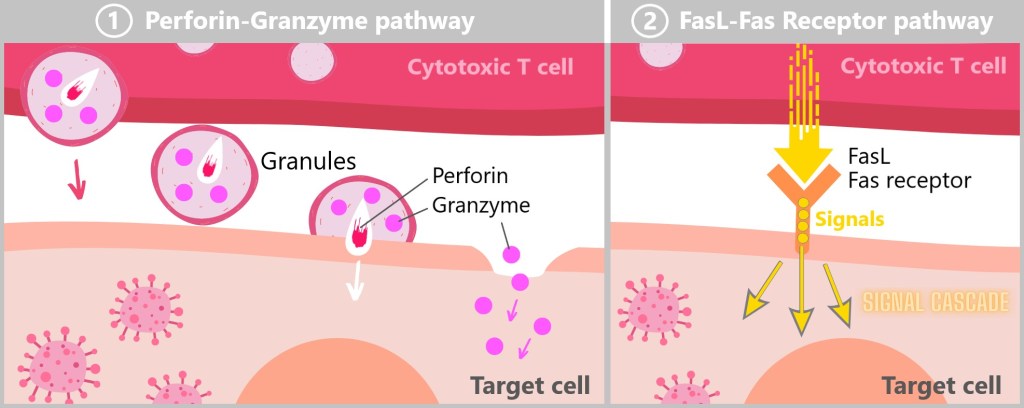

5.5.7. b) Cytotoxic T Cells

5.5.7. c) Plasma Cells

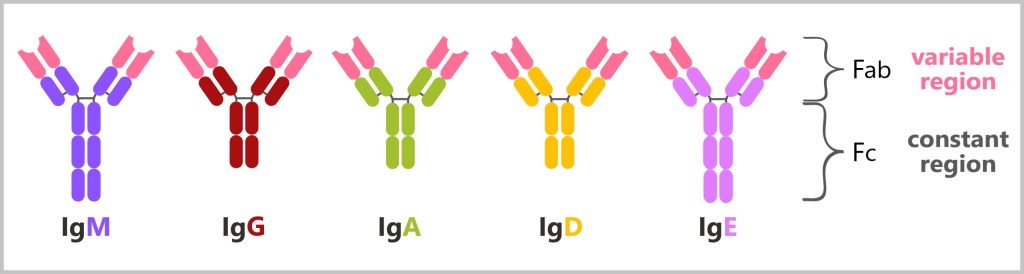

III – Third Line of Defense: The Antibodies

5.5.8. Types of Antibodies

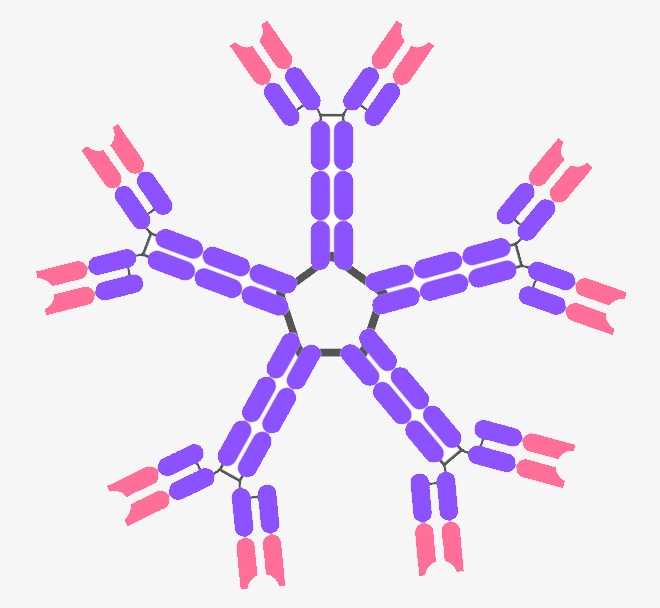

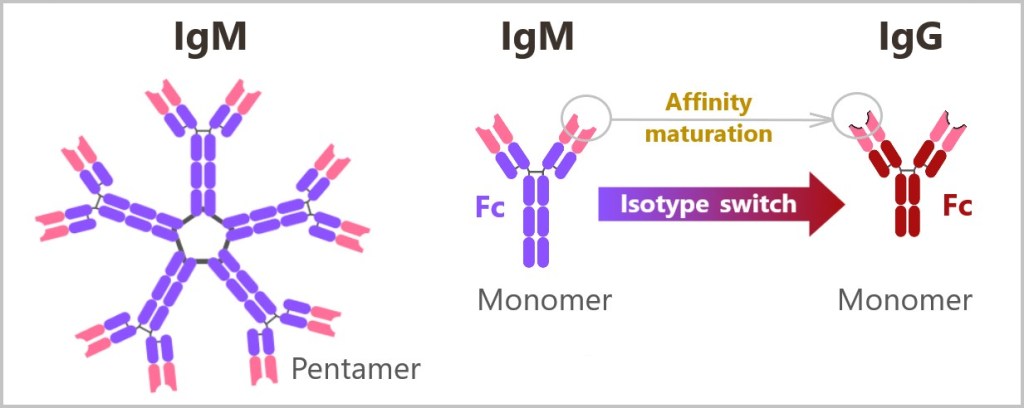

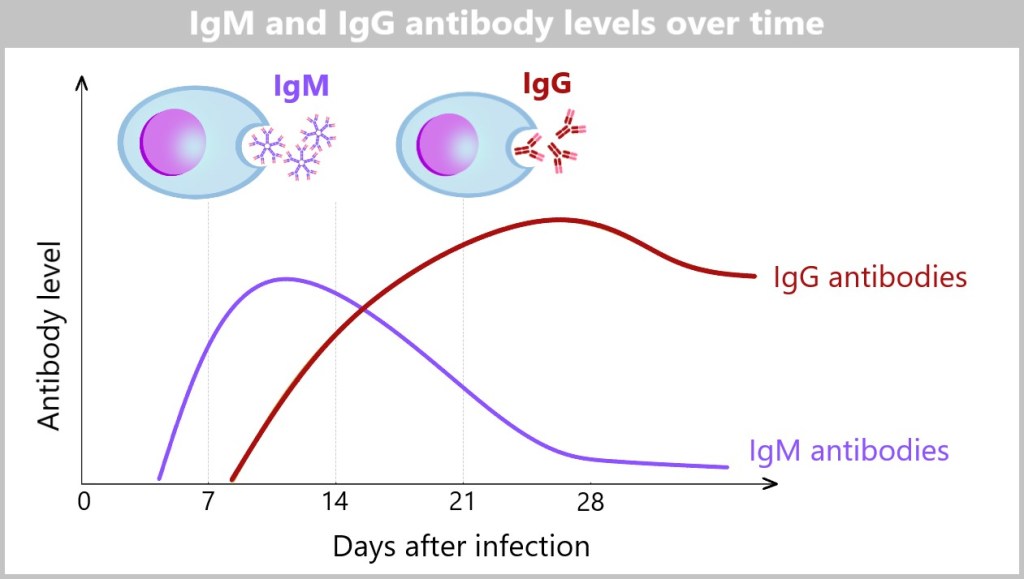

5.5.8. a) IgM – The First Antibody

5.5.8. b) Class Switching (Isotype Switching) to IgG

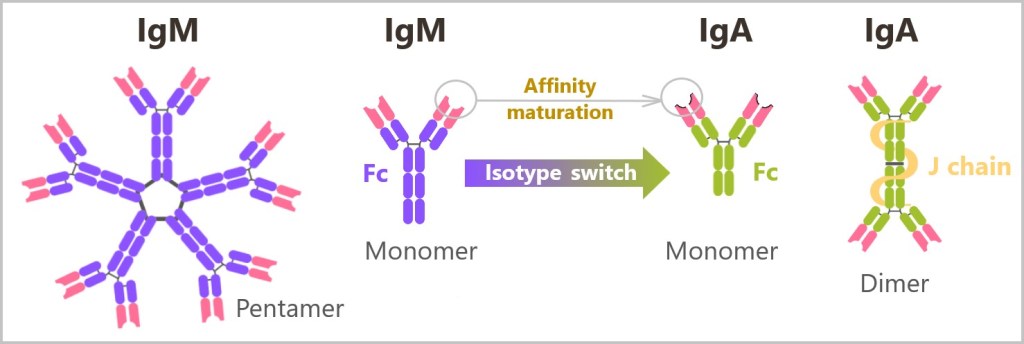

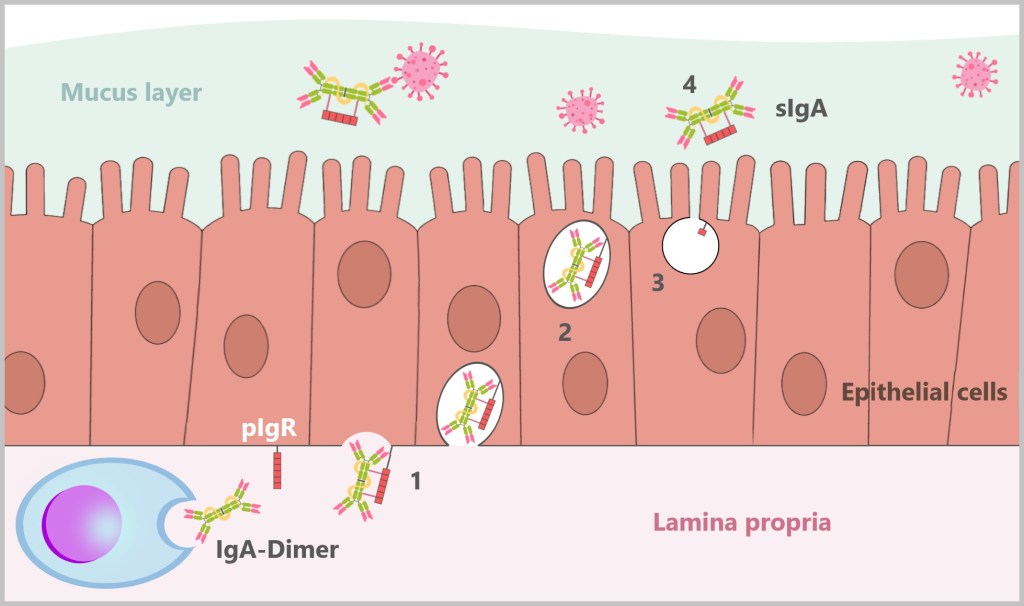

5.5.8. c) IgA – The Protective Barrier of Mucous Membranes

5.5.8. d) Mucosal Immunity: Why IgG Is Unsuitable for This

5.5.9. The Action Phase of Antibodies

5.5.10. Regulatory T Cells and Their Role in the Immune System

5.5.11. Switch-Off Phase

5.5.12. Immunological Memory

5.6. Summary

6. Hidden Defense – The Power of Cross-Immunity

7. Key takeaways

8. Closing words

1. A Look Beneath the Skin – A Journey Within

The organism, the living body of a human being, is a fascinating construct that functions on multiple levels of organization. This organizational structure is the invisible bond that connects the cells, weaves the tissues, and shapes the organs.

To illustrate the complex interplay, let’s zoom in, starting with a look at the organ system level.

Organism ➔ Organ systems

Organ systems are essential units in the human body that combine structure and function. The most important organ systems include the cardiovascular system, the respiratory system, the digestive system, the nervous system, the endocrine system (hormone system), the immune system, the urinary system and the reproductive system. Each of these systems fulfils a unique function that contributes to the overall function of the organism.

The digestive system is responsible for the digestion and absorption of nutrients. The task of the respiratory system is to take in oxygen and remove carbon dioxide. The cardiovascular system moves blood around the body to transport nutrients and oxygen to the cells and remove waste products.

An organ system consists of a single organ or a group of organs that are closely connected. When we zoom in closer, we can examine the individual organs.

Organism ➔ Organ systems ➔ Organs

Organs are important parts of the body that perform specific tasks. Each organ has its own distinct shape and function. The various organs work together like a well-coordinated team. Examples of organs include the heart, lungs, liver, and brain.

The heart pumps blood through the body, while the lungs are responsible for gas exchange. Among many other tasks, the brain controls breathing and the heartbeat. The stomach grinds and mixes food, the intestine extracts nutrients from food and the liver aids digestion and detoxifies.

Organs are made up of different tissues that are closely connected and work together to support the function of the organ. When we zoom in even further, we see the tissues that make up the organ.

Organism ➔ Organ systems ➔ Organs ➔ Tissues

Different tissues in the body fulfil different tasks and are tailored to the needs of the organs they support. By working together, they enable a variety of physiological processes, including movement, sensory perception, digestion and immune defence.

There are four main types of tissues in the human body: muscle tissue, connective tissue, epithelial tissue, and nervous tissue.

To stay with the example of the heart, muscle tissue enables the pumping of blood throughout the body, while nervous tissue controls the electrical signals that regulate heart action. Connective tissue provides structural support and connects the different parts of the heart, while epithelial tissue lines and protects the inner surfaces of the heart.

In the lungs, epithelial tissue facilitates gas exchange. Connective tissue supports the structure and connects the various tissue components. The smooth muscle tissue in the walls of the airways allows for the regulation of airflow. Finally, nervous tissue transmits signals to the brain to control the breathing movements.

Tissues are made up of a variety of cells that come together to perform a specific task. When we zoom in even closer, we can recognize the individual cells.

Organism ➔ Organ systems ➔ Organs ➔ Tissues ➔ Cells

Cells are the fundamental building blocks of tissues. They are often specialized for specific functions within the tissue. They can have different shapes, sizes, and structures, adapted to their respective functions. For example, cells in muscle tissue are specialized for contraction, while cells in epithelial tissue are specialized for protection and absorption.

In addition to the specialized cells that perform specific tasks in the tissue, there is also a special type of cell: stem cells. Unlike other cells in the body, stem cells have the remarkable ability to transform into many different cell types. They are like the „blanks” of the body – not yet committed to a specific task and full of possibilities. When the body needs them, stem cells can become muscle cells, nerve cells, or immune system cells.

Stem Cells

Basically, there are two types of stem cells: embryonic and adult stem cells. Embryonic stem cells are found in the early stages of an embryo, when it is just beginning to develop. These cells have the unique ability to differentiate into virtually any cell type in the human body. They are like the building blocks from which all parts of the body can be constructed.

In the adult body, on the other hand, there are adult stem cells. They are present in various tissues and organs. In contrast to embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells cannot become every cell type in the body. They can only transform into the cell types found in the tissue from which they originate. For example, there are skin stem cells in the skin or liver stem cells in the liver.

What makes these stem cells so special is their ability to repair. If cells in the body are damaged or dead, these stem cells can migrate to this location and ‘build’ new, healthy cells to replace the damaged ones.

Stem cells can divide continuously. This ensures that there is always a supply of stem cells that can differentiate (transform) into the cells the body needs. For example, if liver cells are damaged, liver stem cells can step in, divide and form new, healthy liver cells.

Adult stem cells play an important role in keeping our bodies healthy by producing new cells when needed and repairing damaged tissue.

Cells in tissues communicate and interact with each other via complex signalling pathways and molecules. This communication is crucial for the coordination of cell activities and the maintenance of the function of the tissue as a whole.

A multitude of processes take place in every cell that are crucial for the growth, development, and survival of the organism. Cells are the fundamental building blocks of all living organisms. All life, from the smallest microorganisms to the largest animals, is made up of these tiny yet incredibly complex units. Each cell is an astonishing world of its own, filled with molecules and chemical reactions that make life possible.

One could say: Life begins with the cell.

2. The Cell – The Fundamental Building Block

Life on our planet is a fascinating miracle that begins on a microscopic level in the cell. These tiny building blocks of life are the basis for all living things.

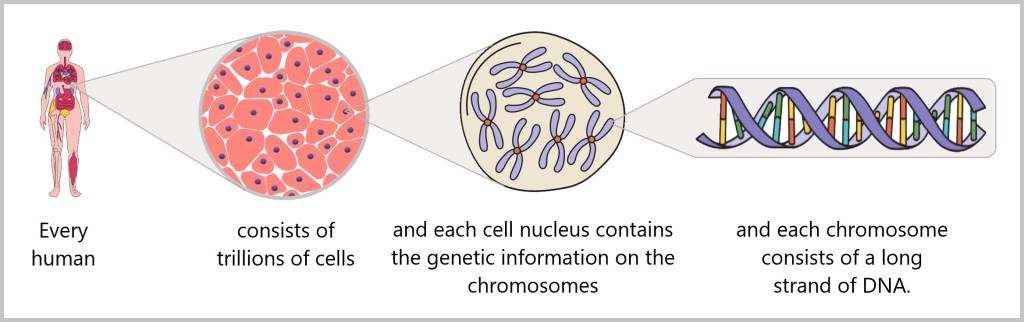

A human being develops from two tiny cells – the egg cell and the sperm cell. In the first few weeks after fertilisation, the embryo undergoes a process in which it turns from a fertilised egg cell into a multitude of cells from which all organs and tissues are formed. By the time the embryo is called a foetus – usually from the eighth week of pregnancy – most of the organs and tissues have been created. From then on, development is mainly focussed on the growth and maturation of these structures. It is estimated that a newborn baby consists of about 20 to 30 trillion cells, while an average adult human has about 30 to 40 trillion cells. A study published in the journal PNAS categorises the human body into 60 tissue systems, 400 major cell types and 1264 separate cell groups.

A brief and concise introduction to cell structure comes from the American digital communication agency Nucleus Medical Media. [Spektrum] It is intended to prepare us for the following explanations.

Although the human body is made up of many different cell types, they all share a similar basic structure. Each cell is surrounded by a protective covering, the cell membrane. Inside the cell, in a gel-like substance called cytoplasm, there are many small, specialized structures known as organelles. One can think of these organelles as tiny machines or workshops within the cell, each performing a specific task.

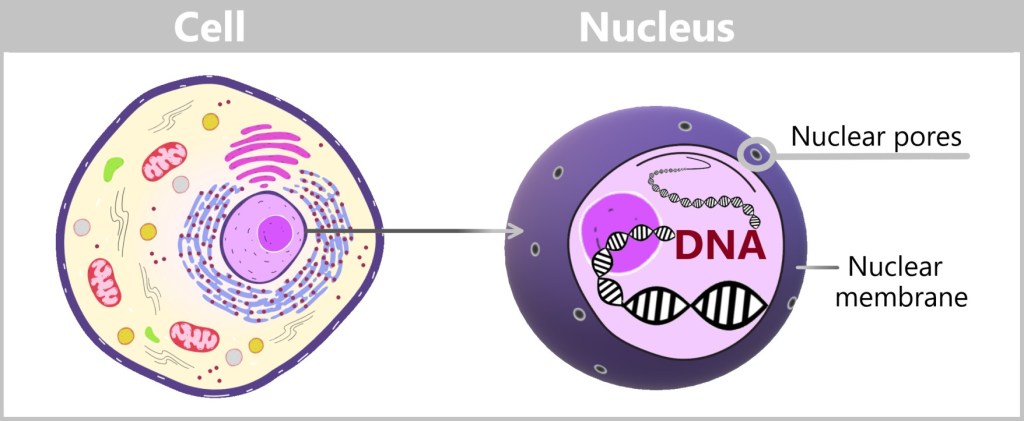

One of these important organelles is the nucleus. The nucleus acts like the control center of the cell – it contains the genetic information (DNA) and provides instructions to the other organelles on how to function. There is one exception: red blood cells. These cells are so specialized for their task that they no longer have a nucleus.

Each cell organelle performs specific tasks.

Nucleus: The nucleus stores the genetic information of the cell (DNA) and controls all the activities of the cell. It is surrounded by a protective layer (cell membrane).

Nucleolus: The nucleolus is a small structure within the nucleus. This is where ribosomes (molecular workshops) are produced, which are necessary for protein production.

Ribosomes: These small structures produce proteins that are essential for many processes in the cell. They can either float freely in the cytoplasm or be attached to the endoplasmic reticulum.

Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): The ER is a network of tubules within the cell that transports proteins and lipids (fats) and also partially produces them.

Golgi Apparatus: The Golgi apparatus acts like a dispatch center. It packages and sends proteins and lipids (which come from the ER) to the correct locations within the cell or outside of it.

Mitochondria: These organelles are often referred to as the ‘power stations’ of the cell because they produce the energy that the cell needs to function.

Lysosomes: Lysosomes act like the cell’s garbage disposal. They contain enzymes that break down old cell components and waste materials.

Cytoskeleton: The cytoskeleton is a network of protein fibers that gives the cell its shape, stabilizes it, and also facilitates movement.

Life, as we understand it, fundamentally requires three basic elements. First, a cell membrane that separates the interior of the cell from the external environment. Second, a metabolism is necessary to extract energy from the environment. And third, genetic information is needed to control and regulate vital processes. All living organisms are based on these three principles: cell membrane, metabolism, and information, which must come together to enable life. In this context, the information contained in DNA is the most essential ingredient for life. [Where does life come from? – a documentary in German language]

Hidden in the depths of the cell lies DNA – the secret of life. It reveals itself as an impressive weave of molecules. These molecules carry the genetic code that determines the diversity and complexity of life. This is why DNA is often referred to as the book of life, as it contains the instructions for the development and functioning of every organism on our planet. By reading the DNA, proteins are produced, which are the actual executors of these instructions. Proteins shape structures, catalyze reactions, and transmit signals that enable life in all its forms. They are the building blocks of all living things and the tools that bring us to life.

From cells to DNA to proteins – life is a breathtaking interplay of molecules and processes that give rise to an infinite variety of forms and functions. In every tiny particle that makes up life lies a deep fascination and an immeasurable wonder.

DNA explanation

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is a biomolecular structure that functions as genetic material in the cells of all living organisms and is located in the nucleus of each cell. It stores all genetic information, serving as the complete blueprint and instruction manual for the structure and function of our bodies.

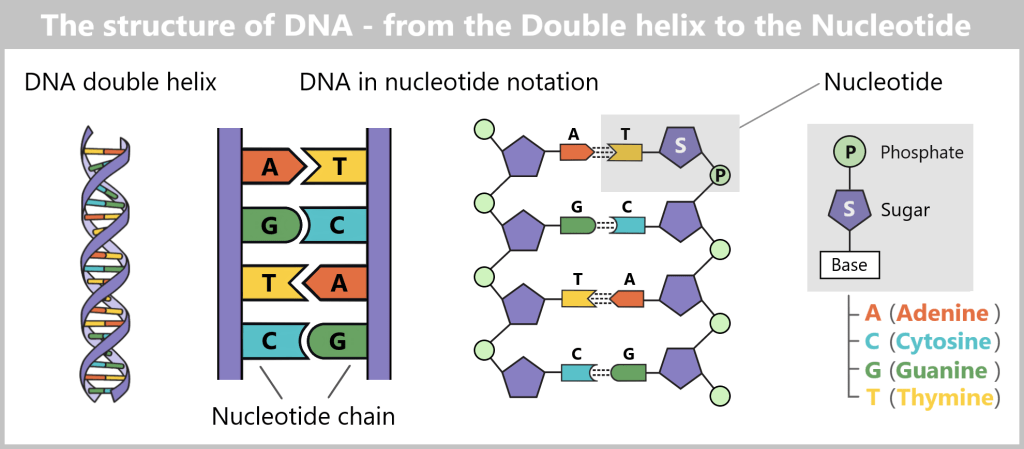

The DNA is structurally similar to a rope ladder. It consists of two long sides that represent the „strands” of DNA. Each „rung” of the ladder is made up of two nucleotides, the chemical building blocks of DNA, which consist of a base, a sugar (deoxyribose), and a phosphate group. The base pairs function as the rungs, while the strands of DNA hold the ladder-like structure together, alternating between sugar and phosphate.

The two nucleotide chains are twisted around their own axis in a helical shape. This structure can be imagined like a twisted ladder or spiral staircase. In biology, this spiral is called the DNA double helix (double because there are two nucleotide chains – double is indeed better). This three-dimensional structure not only gives DNA stability but also saves space. Because if you were to completely unroll the DNA of a human cell, it would measure a remarkable two meters long – life literally hangs by a pretty long but incredibly thin thread!

In DNA, there are four different types of bases: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). These bases always pair in the same way, with adenine (A) binding to thymine (T) and cytosine (C) binding to guanine (G). This binding is complementary, with each DNA strand representing the negative version of the other strand.

The arrangement of these base pairs forms the genetic code, which carries the information for the production of proteins that are necessary for the structure, function and regulation of the body cells, tissues and organs of an organism.

Each gene is a specific segment of DNA that contains the instructions for the formation of a particular protein. Thus, DNA acts as the „cookbook” of life, determining the development and function of an organism and being responsible for the inheritance of traits from one generation to the next. With each cell division, the DNA is copied and passed on to the new cells, ensuring that genetic information is transmitted from generation to generation.

Mutations in the DNA sequence can lead to changes in the structure and function of proteins, which in turn can affect the appearance, health, and behavior of an organism. Some mutations can cause diseases, while others may have no noticeable effects or even be beneficial.

3. Proteins – The Building Blocks of Life

Proteins, which are created by reading the DNA, are the true architects of life. They perform a wide variety of essential functions in the body and are responsible for almost all biological processes. On one hand, proteins serve as structural building blocks and form the foundation for cells, tissues, and organs. They give cells their shape and strength, enabling them to carry out their functions properly.

In addition, proteins are also involved in enzymatic reactions that drive metabolism and regulate vital chemical processes in the body. Furthermore, proteins serve as messengers, enabling communication between cells and tissues. For example, hormones are proteins that transmit important signals throughout the body and control a wide range of physiological responses.

In addition to their structural, enzymatic, and signaling roles, proteins also contribute to immunity by acting as antibodies, protecting the body from diseases and infections. They recognize and bind to foreign substances such as bacteria and viruses, marking them for destruction by the immune system.

Proteins account for up to 40% of the volume of the cytoplasm. So far, there is no exact figure for how many different proteins the human body can produce. Scientists estimate that there are about 20.000 different proteins in the human body, but some studies suggest that there could be even more. The following schematic representations of different proteins are taken from an animation by BioVisions at Harvard University. A real image of a protein can be seen here.

But how and where are these all-rounders created?

4. From Code to Protein – Cellular Mechanisms

4.1. From Signals to Actions

4.2. The Protein Biosynthesis

4.2.1. Transcription

4.2.2. Translation

4.3. The Protein

4.1. From Signals to Actions

Amid the bustling activity within the cell, crucial processes take place that sustain and enable life. One such process is protein synthesis, the building blocks of life. This complex task requires precise coordination and involves a series of steps that occur harmoniously within the cell. These cellular processes are regulated and orchestrated by the cell’s regulatory system.

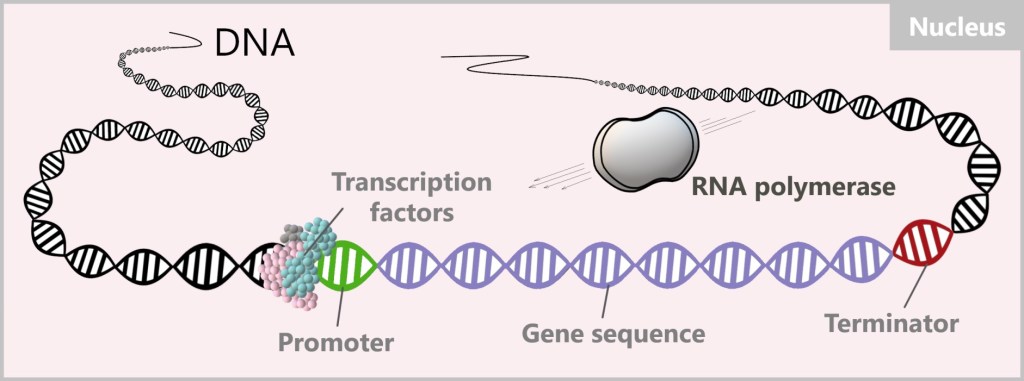

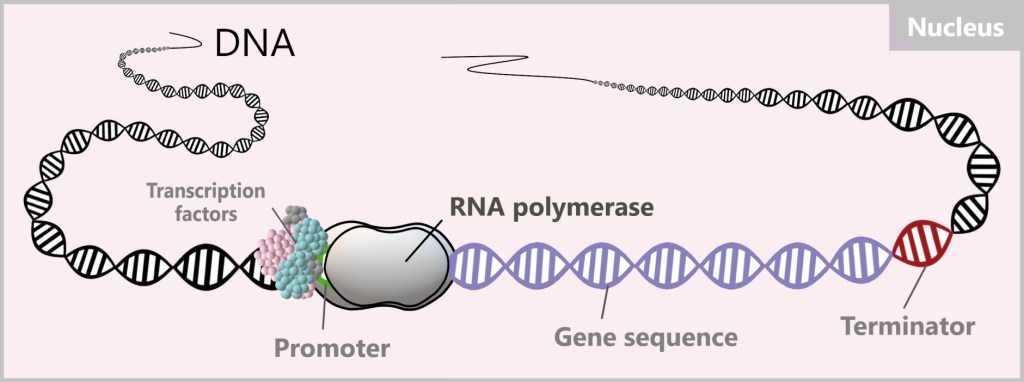

The regulatory system detects external signals or changes within the cell to determine when there is a need for specific proteins. To produce the required proteins, the regulatory system activates so-called transcription factors. These transcription factors can be viewed as a type of production assistants, of which there is a great variety within the cell – estimated to be in the thousands. Each of them has specific permissions and a precise task to carry out. Transcription factors themselves are regulatory proteins.

Activated specific transcription factors now make their way to the nucleus, the location where the book of life – DNA – is found. This book contains all the information about the proteins that the cell can produce, encoded in thousands of genes. Therefore, it is a very precious book because without the book of life, the cell does not know how to produce the proteins. And without proteins, the cell cannot exist. The book of life is kept in a secure place, the nucleus, to ensure it is not damaged. You can imagine this secure location as a vault that can only be accessed with a valid access code.

The nuclear membrane is the security barrier that surrounds the nucleus. It contains tiny nuclear pores that act as gatekeepers. This allows the nucleus to control who can enter or exit. Only those who can identify themselves and present the appropriate recognition signal are allowed to pass through the nuclear pores. [„Rush hour” at the nucleus, „How wriggling tentacles protect our genetic material.”]

The activated transcription factors can pass through the nuclear pores and carry out their tasks in the nucleus. There, they specifically search for particular DNA sequences near the starting point of the target gene, known as the promoter. These DNA sequences serve as anchor points where the transcription factors can bind to activate (or suppress) the transcription of the corresponding genes. By binding the transcription factors to these specific sites, RNA polymerase is attracted, thereby initiating the process of protein biosynthesis.

4.2. The Protein Biosynthesis

The process of protein production is called protein biosynthesis and it takes place in two sub-steps, transcription and translation.

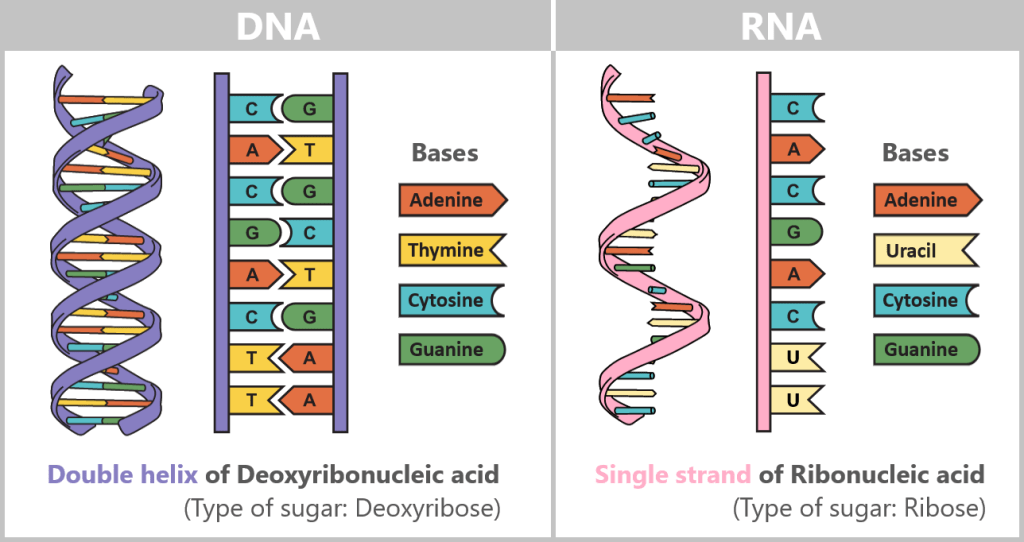

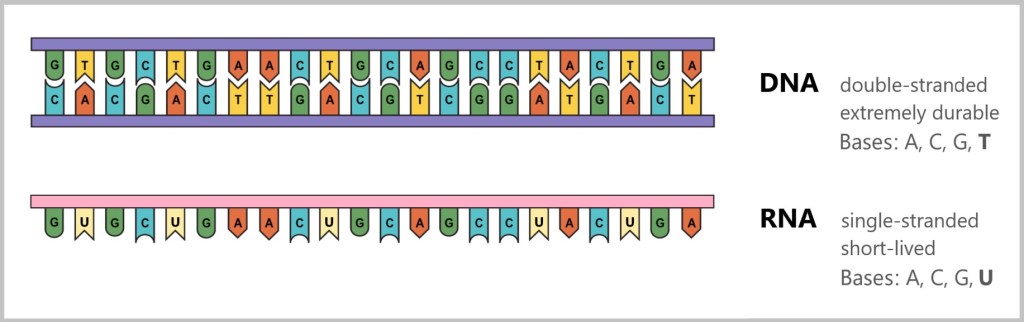

Difference between DNA and RNA

The difference between DNA and RNA is crucial for understanding how life functions at the molecular level.

DNA

DNA stands for deoxyribonucleic acid and is the molecule that contains all the genetic information of an organism. You can think of DNA as a recipe book containing all the instructions a cell needs to produce proteins and thus fulfil various tasks in the body.

Important Properties of DNA:

Structure: DNA has a double helix structure, i.e. it consists of two long strands that look like a twisted ladder.

Base Pairs: DNA is composed of four building blocks known as bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). The bases always form specific pairs: adenine (A) pairs with thymine (T), and guanine (G) pairs with cytosine (C).

Function: DNA stores all the instructions that a cell needs in the long term. It is stable and hardly changes.

RNA

RNA stands for ribonucleic acid and has a structure similar to DNA, but it has some important differences. RNA is used as a „working copy” of DNA when a specific gene needs to be read and translated.

Important Differences to DNA:

Structure: RNA is usually a single strand, while DNA consists of two strands.

Bases: RNA uses almost the same building blocks as DNA, but there is one small difference: instead of thymine (T), RNA contains the base uracil (U).

Sugar: The sugar found in RNA is ribose, while DNA contains deoxyribose. This small difference makes RNA somewhat less stable and more short-lived than DNA.

Why is there mRNA?

mRNA stands for messenger RNA. It is essentially a copy of a specific section of DNA and is needed to convey the instructions from DNA for protein synthesis. Here are the reasons why mRNA is necessary:

DNA protection: The DNA remains in the nucleus because it is very valuable and sensitive. It is not used directly to produce proteins. Instead, a copy is made in the form of mRNA, which is then transported to the cell’s „factories” (the ribosomes) to produce proteins.

Working copy: The mRNA is a temporary copy of a gene. It is degraded after fulfilling its purpose. This makes RNA perfectly suited for short-term tasks, while DNA remains permanent and unchanged in the nucleus.

Why does the mRNA differ in one base (uracil instead of thymine)?

The transition from thymine (T) in DNA to uracil (U) in RNA is evolutionarily driven and is related to the function of the two molecules:

Stability: Thymine is chemically more stable than uracil, which is why it is found in DNA. DNA must remain stable throughout the life of an organism in order to preserve the genetic information.

Efficiency: Uracil is somewhat easier to produce than thymine and is completely sufficient for the short-term tasks of RNA. Since RNA exists only for a short time and is quickly degraded, it does not need to be as stable as DNA. Therefore, uracil is a more energy-efficient solution for RNA.

This division of labour means that the DNA remains protected and unchanged, while the RNA takes over the necessary tasks as a flexible working copy.

4.2.1. Transcription

The process of converting DNA into RNA is called transcription. An enzyme, RNA polymerase, is responsible for the production of RNA. An enzyme is a protein that accelerates biochemical reactions in the body.

Once the transcription factors have bound to the promoter, they act as a platform or anchor point for the RNA polymerase. It places itself on the transcription factors or in their immediate vicinity and initiates the process.

This begins with the unwinding of the DNA double helix, making the DNA sequence accessible. RNA polymerase moves along the DNA sequence and reads it.

During this process, RNA polymerase synthesizes an RNA strand using RNA nucleotides, the building blocks of RNA. The polymerase forms complementary base pairs between the RNA nucleotides and the bases of the DNA sequence. In this pairing, adenine (A) pairs with uracil (U), and cytosine (C) pairs with guanine (G). The difference from DNA is that in the RNA copy, the base thymine (T) is replaced by the base uracil (U), which is a characteristic feature of RNA.

Once a reading step is completed, RNA polymerase closes the DNA behind it. The reading process ends at the terminator, the section at the end of the target gene. The produced RNA and the polymerase then detach from the DNA. In this process, the DNA, the „precious book of life”, remains unchanged and undamaged.

Why is synthesis always in the 5′-3′ direction?

DNA consists of two strands that run in opposite directions. One strand runs in the 5′ to 3′ direction, while the other runs in the 3′ to 5′ direction. These two strands are complementary to each other.

The RNA polymerase binds to the template strand (mold strand), which runs in the 3′-5′ direction, and reads it in that direction. Meanwhile, it synthesizes a new RNA strand in the 5′-3′ direction by adding new RNA nucleotides to the 3′ end of the growing strand.

What do 5‘ and 3’ mean?

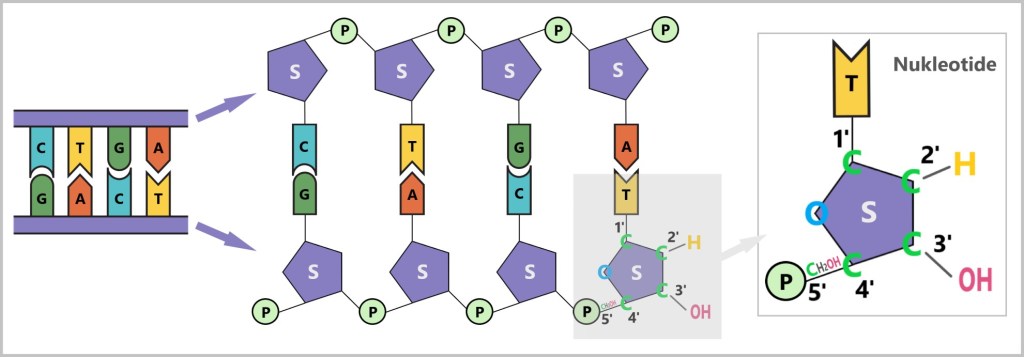

To understand the terms 5‘ and 3’, you need to look at the structure of the sugar in a nucleotide (see figure below). Nucleotides are the chemical building blocks of DNA, each consisting of a base (A,C,G or T), a sugar (Z) and a phosphate group (P). The sugar in DNA is deoxyribose, a molecule with five carbon atoms (C), which are numbered as follows:

1′: Here, the base (A, T, C, or G) is attached.

2′: It carries only a hydrogen atom (-H) in DNA and no hydroxyl group (-OH) as in RNA. This missing OH group gives deoxyribose its name (‚deoxy‘-ribose, since ‚deoxy‘ means without oxygen).

3′: A hydroxyl group (-OH) is located here, which is important for the addition of new nucleotides during synthesis.

4′: It connects the ring of the sugar molecule to the 5′ carbon.

5′: Carries the phosphate group that links the nucleotide to the next one.

(A,C,G,T – bases, S – sugar, P – phosphate group, C – carbon atom)

Why does the synthesis only take place in the 5‘-3’ direction?

The RNA polymerase can only add new nucleotides to the 3′ end of the growing strand because a hydroxyl group (-OH) is present there. This OH group enables the chemical reaction in which the phosphate group of the new nucleotide is bound to the strand. As the 5‘ position of the new nucleotide is already occupied by a phosphate, the chain extension can only take place in the 5’-3′ direction.

How does reading and synthesizing work?

The RNA polymerase moves along the template strand of the DNA in the 3‘-5’ direction. As it does so, it adds complementary RNA nucleotides to the new RNA strand, which grows in the 5‘-3’ direction. The new nucleotides are always attached to the free 3′-OH group of the growing strand.

Detailed information on this topic can be found here and here.

The resulting RNA is a copy of the original DNA code.

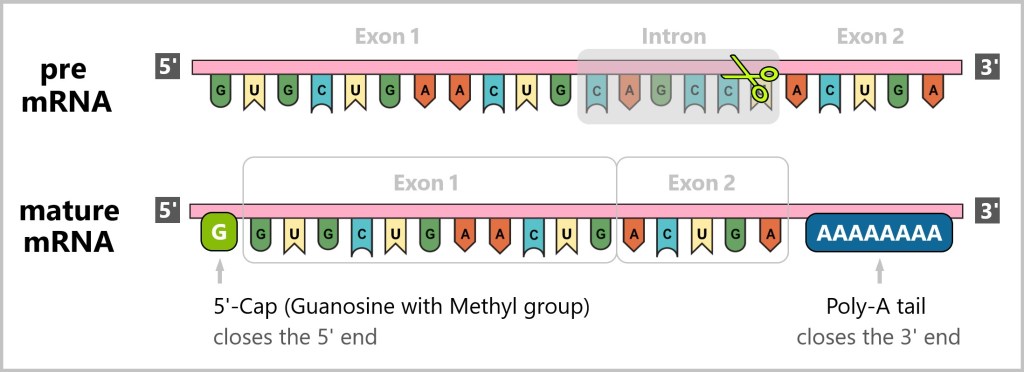

The RNA that is directly produced from transcription is called pre-mRNA and must undergo further processing steps to become mature mRNA, which is ready for translation. This processing includes splicing, where introns (non-coding regions of a gene) are removed and exons (coding regions of a gene) are joined together.

Introns and exons are not constant but variable, and they play an important role in gene regulation and diversity. This means that depending on the type of protein that needs to be produced, different exons can be combined and introns removed. Through this process, cells can produce a variety of proteins that perform different functions.

Additionally, a 5′-cap is added to the 5′-end of the mRNA, and a poly-A tail (a series of adenine nucleotides) is added to the 3′-end.

The addition of the 5′-cap and the poly-A tail to mRNA serves important functions.

The 5′-cap and the poly-A tail ensure the stability of the mRNA, enable its safe transport and ensure that it is efficiently utilised for protein production.

5′-Cap

Protection against degradation: The 5‘-cap is a modified guanine base that is attached to the 5’-end of the mRNA. It protects the mRNA from degradation. Without this protection, the mRNA could be rapidly degraded before it reaches translation.

Facilitation of transport: The 5′-cap also assists in the transport of mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. It is recognized by specific transport proteins that guide the mRNA through the nuclear pores into the cytoplasm.

Initiation of translation: The 5′-cap is crucial for the recognition and binding of mRNA to the ribosomal subunit, which is necessary for the initiation of translation. Without the cap, the mRNA cannot be efficiently recognized by the ribosome.

Poly-A-tail

Stability of the mRNA: The poly-A tail consists of a series of adenine nucleotides attached to the 3′ end of the mRNA It protects the mRNA from degradation by enzymes that break down RNA from its 3′ end. Longer poly-A tails extend the lifespan of the mRNA in the cytoplasm, leading to more efficient protein production.

Regulation of Translation: The poly-A tail also contributes to the regulation of translation. It controls the frequency of mRNA translation by influencing the interaction with ribosomes and other proteins necessary for translation.

Stability during Translation: The poly-A tail can help maintain the mRNA in a specific spatial conformation that is necessary for efficient translation.

The mature mRNA, which contains the genetic blueprint for the protein to be produced, diffuses through the nuclear pores into the cytoplasm of the cell, where it is recognized by the ribosomes. This initiates the next step – translation.

Biotech Made Easy offers a short visualisation of the transcription process, which makes the process easy to understand.

Another short animation of the transcription comes from the DNA Learning Centre. It shows the process in real time.

4.2.2. Translation

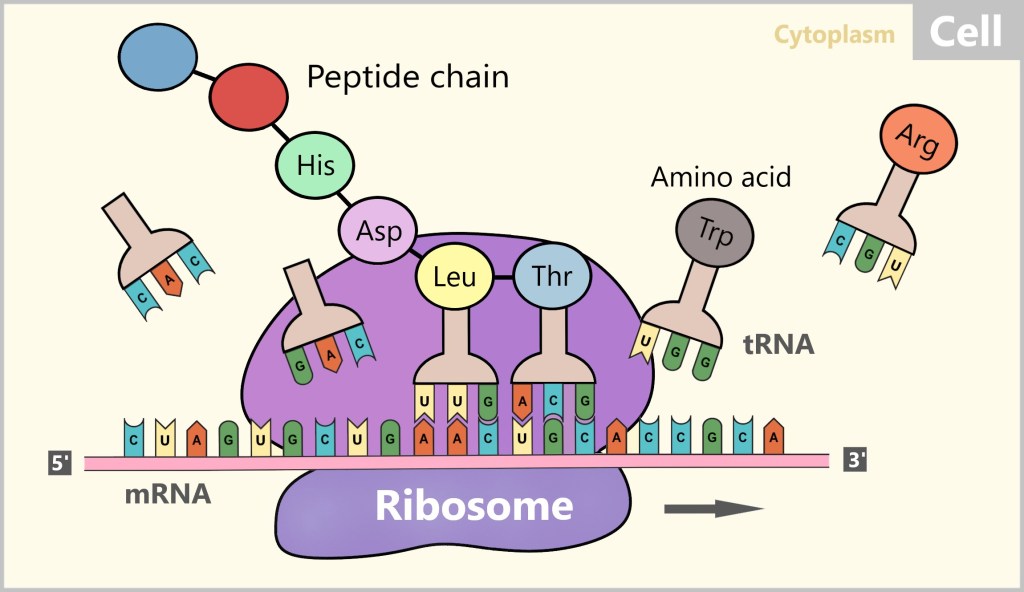

Translation is the process by which the genetic information stored in the mRNA is converted into a sequence of linked amino acids to form proteins. This important transformation takes place at the ribosomes, the protein factories of the cell. The ribosomes act as machines that read the mRNA and arrange the amino acids according to the instructions of the mRNA.

In eukaryotes like humans, two types of ribosomes are distinguished: free ribosomes and bound ribosomes (see Fig. 15). A significant portion of the ribosomes is found freely in the cytoplasm, while others are bound to the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The ribosomes attached to the ER produce proteins that are either intended for export from the cell or for incorporation into the cell membrane. Both free and membrane-bound ribosomes have a similar structure and function. For our further consideration, we will focus on the free ribosomes.

The ribosome binds to the mRNA and then moves along the mRNA sequence from the 5′ end to the 3′ end. During this process, the mRNA slides through the ribosome like a conveyor belt and is scanned step by step. Three consecutive bases, known as codons, are read at a time. When the ribosome reaches the start codon (AUG), translation begins.

During translation, the ribosome reads each codon on the mRNA and assigns it a corresponding transfer RNA (tRNA) with the appropriate amino acid. The tRNA carries a specific sequence of three nucleotides, known as an anticodon, which is complementary to the codon of the mRNA.

When the anticodon of a tRNA pairs with the corresponding codon of the mRNA, the amino acid carried by that tRNA is linked to the growing peptide chain. Peptides are short chains of amino acids, and these amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. This process repeats as the ribosome moves along the mRNA, scanning each codon.

The amino acids that are linked together are connected by peptide bonds, forming the peptide chain of the emerging protein. Translation ends when the ribosome reaches a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) on the mRNA. At this point, the newly formed peptide chain – the unfinished protein – is released, and the ribosome detaches from the mRNA.

Here, too, there is a brief and clear visualisation of the Biotech Made Easy translation process.

4.3. The Protein

The protein initially exists as a chain of a specific sequence of amino acids. For the newly synthesized protein to become functional, it must fold into the correct three-dimensional shape. The spatial arrangement of the amino acid chain – its specific three-dimensional form – is crucial for the protein to fulfill its role in the body, whether as an enzyme (a molecule that accelerates chemical reactions), a structural protein (which gives cells and tissues their shape and strength), or a hormone (a signaling molecule that regulates various bodily functions).

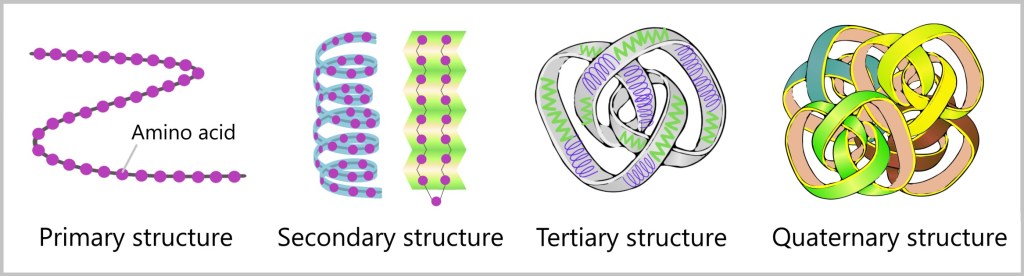

Every protein has its own blueprint that determines how it will fold to fulfill its function. The amino acid chain forms the primary structure, from which repeating patterns arise, referred to as the secondary structure. Electrostatic attractions and other chemical bonds then bring different parts of the protein together, resulting in its final shape – the tertiary structure. Sometimes, multiple proteins even form complex structures known as quaternary structures.

The path to proper folding is not always straightforward. Sometimes proteins can misfold, especially when they are too close to each other. In these moments, helpers come into play – the chaperones, which are proteins themselves. They protect the peptide chain from unwanted interactions and facilitate the folding process.

However, some proteins are too large to fold on their own. Here again, chaperones come into play, guiding the proteins to another helper – a cylindrical structure called a chaperonin. In this secure environment, proteins can fold undisturbed. The fully folded proteins are now ready to begin their work inside or outside the cell.

The video „Chaperones – Protein Folding” illustrates the process of protein folding in an engaging way.

Errors in protein folding

The process of protein folding is crucial for the biological functionality of the cell and is carefully regulated. A misfolded protein can lose its normal function or even become harmful. Errors in protein folding can have serious impacts on cellular processes and lead to various diseases. Examples include Amyloidosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease.

The „Protein Folding Problem”

The „protein folding problem” is one of the central puzzles of biology. It refers to the difficulty of predicting the three-dimensional structure of a protein based on the sequence of its amino acids. Proteins are made up of hundreds of amino acids that fold into complex spatial structures, and the DNA sequence alone does not provide direct information about this structure. The challenge of protein structure prediction lies in inferring the spatial arrangement of the amino acids from the genetic information. The magnitude of this challenge becomes apparent when considering that the number of theoretical possibilities for how a protein could fold before achieving its final 3D structure is enormous.

Scientists from various disciplines have been working on solving this puzzle for more than 50 years. A groundbreaking development in this field is the creation of ‚AlphaFold‚ by Deepmind, an AI that handles protein structure prediction with unprecedented accuracy. This achievement could revolutionise the understanding of protein folding.

Nevertheless, the exact process of protein folding is still not fully understood and remains a current area of research in biochemistry.

Proteins: Their Lifespan and Regeneration

Like any product, a protein has a limited lifespan. Once a protein has fulfilled its function or is damaged, it is broken down. This continuous process occurs in all cells of the body.

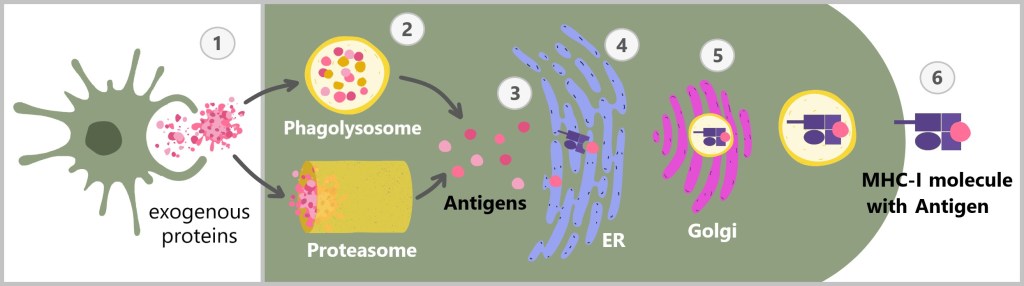

A specialized enzyme called the proteasome is involved in this process. The proteasome cuts the protein into smaller fragments (peptides), which are then further broken down into individual amino acids. These amino acids can be reused to produce new proteins. This ensures that faulty or no longer required proteins are removed and the cell’s resources are utilised efficiently.

Protein degradation and its connection to the immune system

The degradation of proteins is an essential process that has far-reaching effects on various systems in the body, including the immune system. The specific role this process plays in the immune system will be discussed in more detail in the following chapters.

5. The Body’s Shield – Our Immune System

Our immune system is the impressive legacy of evolution. It is a fascinating micro-world that works in secret – an army of immune cells that have developed into masterpieces of adaptation over millions of years. These tiny fighters stand ready day and night to protect us from the countless threats that we often don’t even realise are there. They watch over us while we sleep, fight for us without us realising it, and are ultimately the reason why we can live and breathe.

To ensure survival, all higher organisms have developed an immune system that fends off pathogens, prevents infections, or contains them. The immune system is composed of a variety of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to protect the body.

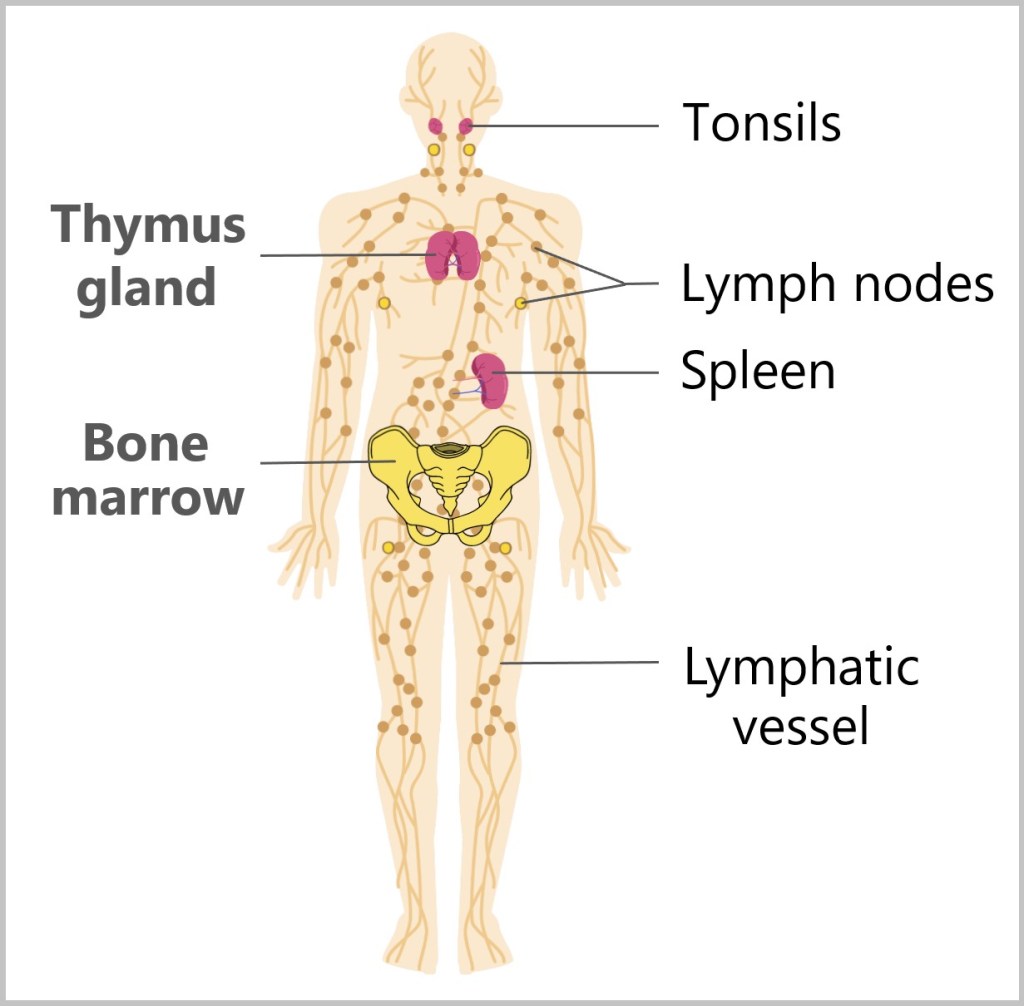

The key components include white blood cells (leukocytes), which come in various forms and have different functions, as well as lymphatic organs such as the bone marrow, thymus gland, spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes.

Fig. 19: Components of the immune system

In addition, the immune system has its own transport network, the lymphatic system, which carries lymph (a watery, slightly milky fluid) and immune cells through lymphatic vessels across the body, enabling them to quickly reach and combat infection sites.

The interaction between immune cells is highly complex and will be simplified here. Although this presentation is already quite challenging, the actual processes in the body are even more intricate and not yet fully understood. To make this easier to grasp, we will focus on the key immune cells and their most important processes.

5.1. Origin of Immune Cells

5.2. Mechanisms of Immune Recognition: SELF vs. NON-SELF

5.3. The Nonspecific Immune Defense

5.4. The Complement System

5.5. The Specific Immune Defense

5.6. Summary

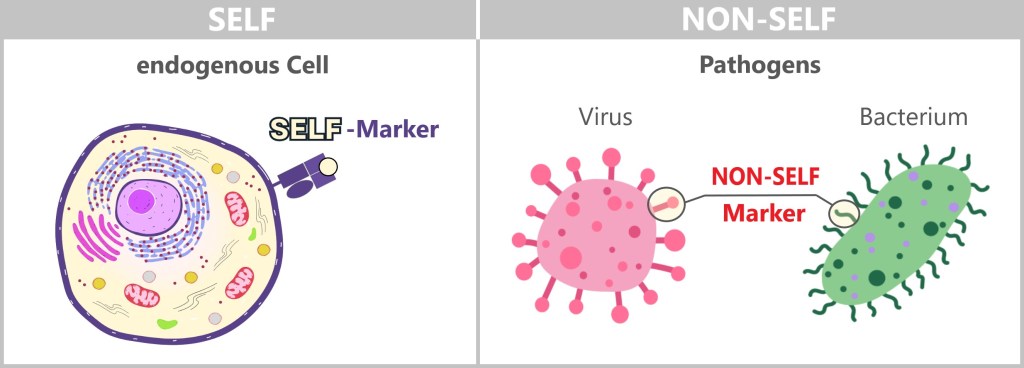

The basic principle of the immune system is based on distinguishing between NON-SELF and SELF, a mechanism that is present from birth.

To defend itself against invaders, the body must be able to differentiate between foreign microorganisms and its own tissue. Not everything foreign is dangerous, so the immune system also needs to distinguish between harmless foreign substances (such as dust, pollen, or food) and harmful ones. Anything that causes illness is considered dangerous to the body, meaning it is pathogenic. The term pathogens encompasses all foreign entities that can cause disease. Pathogens include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.

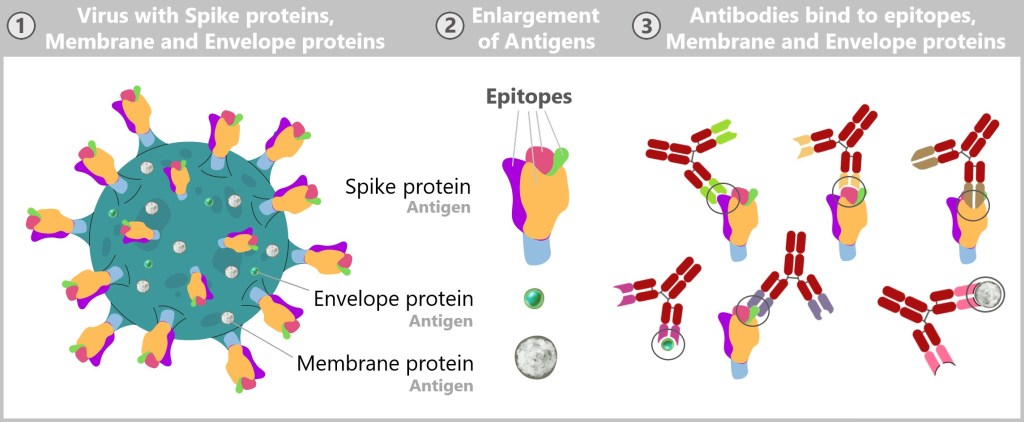

The immune system recognizes so-called antigens based on the structures on the surface of pathogens or other foreign substances. The term ‚antigen‘ means ‚antibody generating‘. These antigens are typically proteins or polysaccharides and serve as „recognition markers” that signal to the immune system that a foreign body is present.

The immune system’s response to anything NONSELF is an immune response. It involves a variety of processes aimed at eliminating the threat of foreign substances and maintaining the integrity of the body.

The right balance between tolerance and defence reaction as well as the strength of the reaction are a real challenge for the immune system. This only works if the individual components of the immune system work together harmoniously.

Throughout evolution, coordinated defense systems have developed to work together. In general, there is a distinction between the innate (nonspecific) and adaptive (specific) immune defenses. The innate immune system is the body’s first line of defense against pathogens. Specialized immune cells respond to threats based on a pre-programmed response. In contrast, the adaptive immune system is highly specialized and targets specific pathogens with precision, recognizing and eliminating them in a targeted manner.

Before we dive deeper into the immune defense, let’s take a look at the origin of immune cells and the mechanisms the immune system uses to differentiate between foreign and self-cells. In this context, key terms and concepts will be introduced, which will be repeatedly referenced throughout the discussion.

5.1. Origin of Immune Cells

Blood cells and immune cells originate from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. These stem cells are the common source for both blood cells and immune cells, as immune cells are an essential part of the blood. The differentiation of these stem cells follows either the myeloid or lymphoid lineage, leading to the development of various cells involved in both the innate (nonspecific) and adaptive (specific) immune systems.

In adults, blood formation (hematopoiesis) primarily occurs in the bones of the pelvis, sternum, ribs, and parts of the spine. These bones contain red bone marrow, which houses the stem cells that give rise to both blood and immune cells. In children, blood formation also takes place in the long bones of the arms and legs, such as the femur and humerus. As individuals age, this bone marrow is gradually replaced by fat-rich yellow bone marrow, causing blood formation to become mainly concentrated in the pelvis and spine.

As shown in the illustration, immune cells develop from two main lineages:

Myeloid Lineage

This line leads to the formation of cells of the innate immune system, including:

- Neutrophil granulocytes

- Eosinophil granulocytes

- Basophil granulocytes

- Mast cells

- Monocytes (which develop into macrophages and dendritic cells)

Lymphoid Lineage

This line forms the cells of the adaptive immune system:

- T lymphocytes

- B lymphocytes

Natural killer cells also originate from the lymphoid lineage but are part of the innate immune system.

Our blood

On average, we adults have between 5 and 6 litres of blood in us. Blood is a fluid tissue that fulfils a variety of vital functions in the body. It consists of a liquid part, the blood plasma, and three solid components, the blood cells. Blood cells make up around 45 per cent of the total blood volume. There are three main types of blood cells: erythrocytes, thrombocytes and leucocytes. Each type of blood cell has specific functions.

Erythrocytes (red blood cells)

Function: Transport of oxygen from the lungs to the tissues and return transport of carbon dioxide to the lungs.

Proportion: Approximately 45% of the total blood volume (hematocrit).

Quantity: Approximately 4.5 to 5.9 million cells per microliter of blood.

Size: About 6-8 micrometres in diameter.

Lifespan: About 120 days.

Characteristics: Erythrocytes have no nucleus, which allows for more space for hemoglobin. The absence of a nucleus means that they cannot divide or synthesize proteins. Their unique structure and the properties of their cell membrane enable them to withstand the mechanical stresses of the bloodstream for a long time.

Thrombocytes (platelets)

Function: Important for blood clotting and wound closure. They form blood clots to stop bleeding.

Proportion: Less than 1% of the total blood volume.

Quantity: Approximately 150.000 to 450.000 platelets per microlitre of blood.

Size: About 2-3 micrometres in diameter.

Lifespan: 7-10 days.

Leukocytes (white blood cells)

Function: Combatting germs and pathogens, as well as forming antibodies.

Proportion: Less than 1% of the total blood volume.

Quantity: About 4.000 to 11.000 cells per microlitre of blood.

Subgroups:

Neutrophil granulocytes: 50-70% of leucocytes; part of the innate immune system and important for fighting bacterial infections. Lifespan: 5-90 hours in blood; 1-2 days in tissue. Size: 10-12 micrometres in diameter.

Eosinophil granulocytes: 1-4% of leucocytes; part of the innate immune system and important in combating parasites and allergic reactions. Lifespan: 8-12 hours in blood; 8-12 days in tissue. Size: 12-17 micrometres in diameter.

Basophil granulocytes: <1% of leukocytes; part of the innate immune system and involved in allergic reactions and the release of histamine. Lifespan: 1-2 days in the blood. Size: 10-14 micrometres in diameter.

Lymphocytes: 20-40% of leucocytes; play a key role in the adaptive immune response. Lifespan: A few days to several years. Size: 6-10 micrometres in diameter for small lymphocytes and up to 15 micrometres for larger lymphocytes.

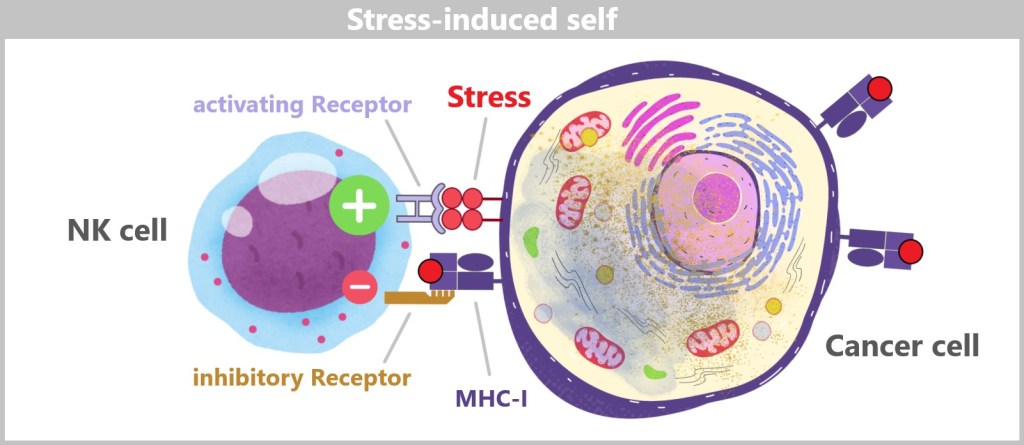

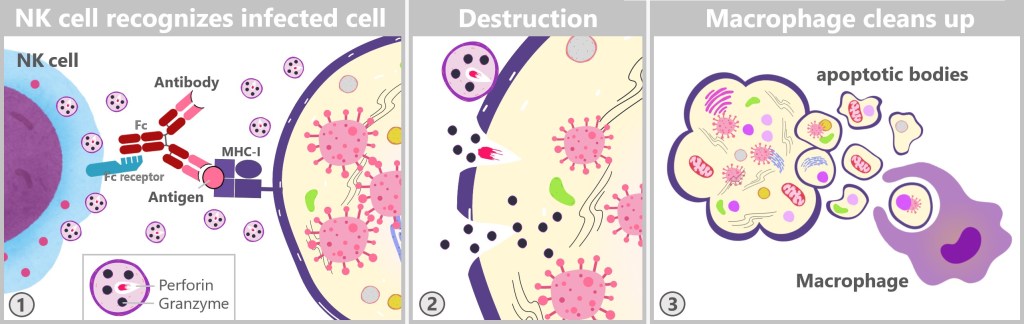

Natural killer cells: 5-15% of lymphocytes; part of the innate immune system, responsible for killing virus-infected cells and tumour cells. Lifespan: Weeks to months. Size: 10-15 micrometres in diameter.

Monocytes: 2-8% of leucocytes; precursor of macrophages and dendritic cells. Lifespan: 1-3 days in the blood; weeks to months in the tissue as macrophages or dendritic cells. Size: 15-20 micrometres in diameter.

Mast cells: Although they do not circulate in the blood, mast cells in tissues (e.g. skin, mucous membranes) are important for the defence against parasites and play a key role in allergic reactions by releasing histamine and other mediators. Lifespan: Weeks to months in the tissue. Size: 10-16 micrometres in diameter.

Blood plasma

Proportion: About 55% of the total blood volume.

Composition: Primarily composed of water (approximately 90 percent).

Function: Transport of nutrients, waste products and hormones.

5.2. Mechanisms of Immune Recognition:

SELF vs. NON-SELF

The distinction between SELF and NON-SELF is primarily made by specialized immune cells that specifically scan the surfaces of cells – both those of the body and of pathogens. Since cells neither have eyes nor ears, they must make contact to determine whether a protein belongs to a friend or foe. For this purpose, they are equipped with a variety of receptors.

Body cells carry so-called SELF markers on their surface. These markers are specific molecules or receptors that are recognized by the immune system and are typically not attacked.

Pathogens, on the other hand, possess specific structures on their surface that are not present on the body’s own cells. Similarly, mutated or damaged cells reveal themselves through changes on their surface. These structures can be interpreted as NON-SELF markers, prompting the immune system to trigger a defensive response.

But how do immune cells communicate with each other to ensure a coordinated response to threats? The answer lies in signaling molecules called cytokines and chemokines.

Cytokines are small proteins that act like signaling beacons, controlling the behavior of immune cells. They regulate the growth, activation, and function of immune cells and play a crucial role in managing inflammatory responses. Depending on the situation, they can either amplify or dampen the immune response.

Chemokines, on the other hand, direct the movement of immune cells throughout the body. They act as navigators, guiding immune cells to the site of infection or inflammation. In this way, they ensure that the body’s defenses are activated precisely where they are needed.

SELF-Marker

SELF-markers, also known as autoantigens, serve as identifiers for the body’s own tissues. During its development, the immune system learns to recognize and tolerate these markers in order to avoid autoimmune reactions. The immune system has several mechanisms in place to achieve this, with three important ones highlighted here:

a) SELF-Marker: MHC Molecules

b) SELF-Marker: CD47 Molecule

c) SELF-Marker: Sialic Acid

a) SELF-Marker: MHC Molecules

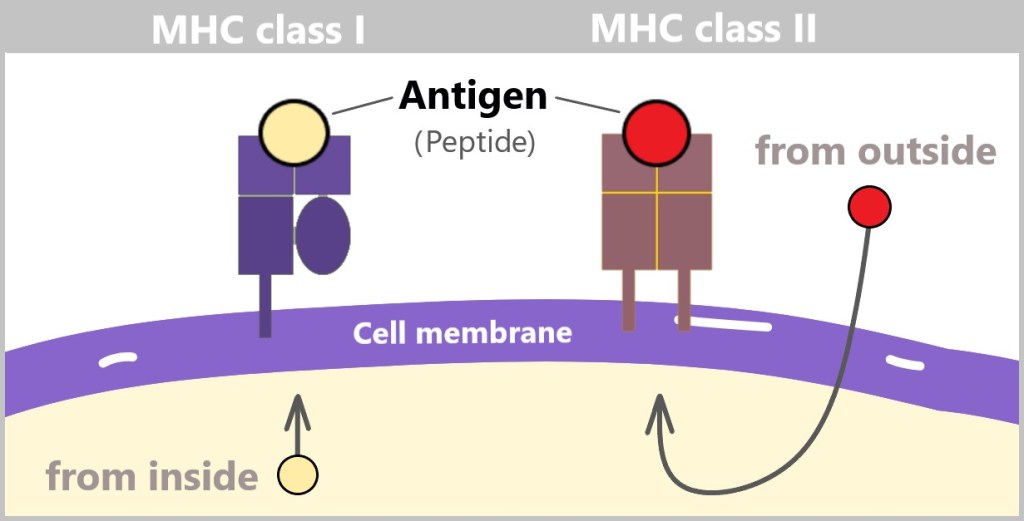

An important example of SELF-markers are MHC molecules. The term MHC stands for Major Histocompatibility Complex and refers to special proteins on the cell surface that function as receptors. These receptors primarily present the body’s own protein fragments. By doing so, the cell signals to the immune system that it belongs to the body and does not pose a threat.

However, MHC molecules can also present foreign protein fragments. These usually come from pathogens or diseased cells, such as cells infected by viruses. By displaying such foreign fragments on the cell surface, the immune system can recognize infected or abnormal cells and initiate an appropriate defense response.

Major indicates the significant importance of these genes for immune recognition.

Histocompatibility is composed of ‚histo‘ (tissue) and ‚compatibility‘, referring to how well tissues are compatible or acceptable between different individuals. MHC plays a crucial role in organ transplantation.

Complex refers to the group of genes that work together to perform a complex function.

There are two main classes of MHC molecules:

MHC class I molecules are found on almost all nucleated cells in the body.

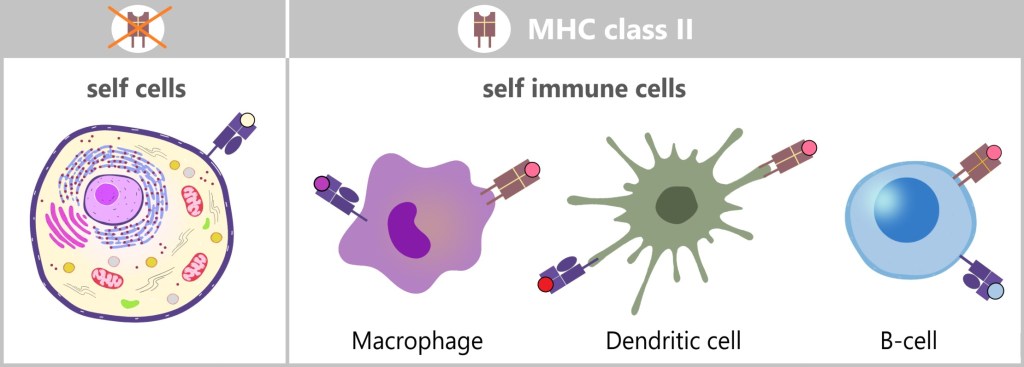

MHC class II molecules are mainly found on specific immune cells.

The following simplified graphic illustrates the difference between the two classes. Both MHC class I and MHC class II molecules are anchored in the cell membrane and present protein fragments (peptides) that serve as antigens. A structural difference is that MHC class I molecules have a single anchoring point in the cell membrane, while MHC class II molecules have two anchoring points.

In general, MHC complexes serve the purpose of antigen presentation by providing the immune system with information about the state of the cell.

Antigen presentation

MHC-I presents antigens that originate from inside the cell. As mentioned in section ‚4.3. The protein‘, cells continuously degrade old or damaged proteins. In the process, proteasomes break down these proteins into smaller fragments, so-called peptides. These peptides can originate from the body’s own proteins and signal to the immune system that the cell is healthy. However, if the cell is infected with a virus or otherwise becomes abnormal, the MHC-I molecule presents peptides from foreign or altered proteins. This alerts the immune system that the cell is potentially dangerous and needs to be eliminated.

MHC class I molecules are expressed by all nucleated cells.

On the left is a healthy cell presenting its own normal peptide via an MHC class I molecule. This indicates that the cell is healthy and not infected. The MHC-I molecule signals to the immune system that no action is needed. In the middle is a virus-infected cell, which also carries an MHC class I molecule but presents a foreign peptide derived from a virus. This viral peptide alerts the immune system that the cell is infected, potentially triggering an immune response. On the right is a cancer cell that presents a modified peptide through an MHC class I molecule. This peptide has been altered due to genetic mutations occurring during cancer development. It signals to the immune system that the cell is abnormal and should be removed.

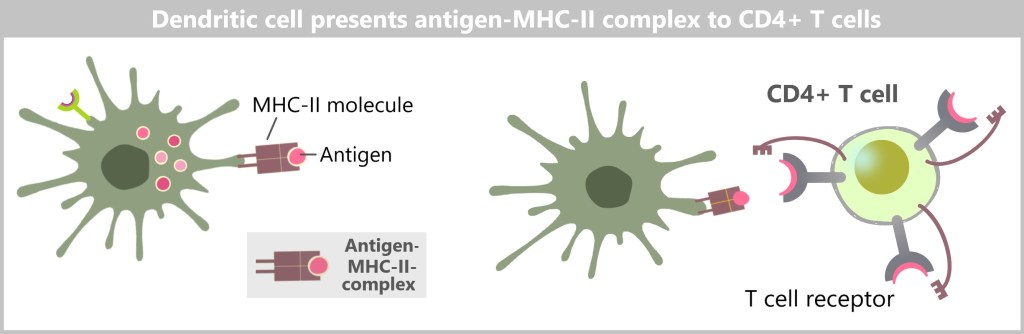

MHC class II, on the other hand, presents antigens that originate from outside the cell. MHC-II molecules are expressed only by specialized immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells. These cells engulf foreign material, such as bacteria or other pathogens, break it down into smaller fragments (antigens), and then present these on their cell surface. The antigens presented in this way activate specific immune cells that coordinate a targeted immune response.

MHC molecules enable the immune system to differentiate between the body’s own cells and foreign or altered cells. This is crucial for protecting healthy cells and at the same time triggering an immune response against potentially harmful invaders or abnormal cells.

The short animation on antigen presentation: MHC class I vs. MHC class II illustrates the relationships explained above.

MHC molecules and their diversity

What are MHC molecules?

MHC molecules are special proteins on the surface of our cells. They help the immune system to differentiate between our own and foreign substances, such as pathogens. MHC molecules are formed by certain genes in our body.

What are alleles?

The genes that produce MHC molecules come in many different versions, known as alleles. Each person has a unique combination of alleles, which causes their MHC molecules to appear slightly different from one individual to another.

Why are there so many versions?

There are hundreds of different alleles within the population. This vast diversity helps the immune system recognize a wider range of pathogens. As a result, some people are better protected against certain diseases than others – which is an advantage from an evolutionary perspective. [Major Histocompatibility Complex]

How do MHC molecules work?

Each MHC molecule can bind small fragments of proteins, so-called peptides. These peptides are produced when proteins are broken down in the body. MHC molecules then present these peptides on the cell surface so that the immune system can recognise whether the cell is healthy or has been attacked by a virus or other pathogens.

Why is this diversity important?

The diversity of MHC molecules means that different people can bind and present different peptides. This makes it more difficult for pathogens to infect all people in the same way, as each person’s immune system responds differently to them.

Organ transplantation and MHC molecules

The diversity of MHC molecules is also the reason why finding compatible organ donors is challenging. If the donor’s MHC molecules do not match well with those of the recipient, the recipient’s immune system may recognize the new organ as foreign and attack it. Therefore, in organ transplantation, the MHC molecules of the donor and recipient must be carefully compared to reduce the risk of rejection.

b) SELF-Marker: CD47 Molecule

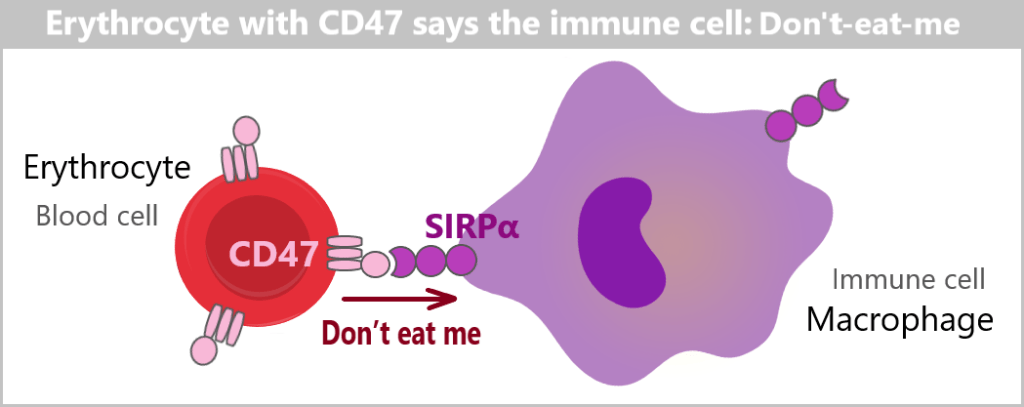

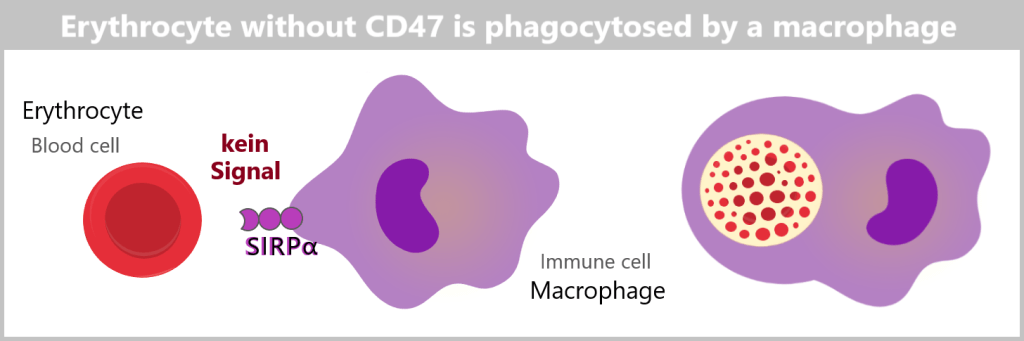

Another important SELF-marker on the surface of cells is the molecule CD47. This molecule acts as a ‚Don’t eat me‘ signal, meaning it prevents immune cells from destroying the cell.

CD47 plays a crucial role in the regulation of the immune response and the protection of blood cells. In contrast to MHC class I molecules, which are only found on nucleated cells, CD47 is found on all cell types, including nucleus-free cells such as erythrocytes (red blood cells) and thrombocytes (platelets).

CD47 binds to a receptor protein called SIRPα (Signal Regulatory Protein Alpha), which is present on the surface of immune cells. This binding sends a signal that prevents the immune cell from attacking the cell. This ensures that healthy, self-cells are not destroyed by the immune system.

If the CD47 marker is missing or not functioning properly, the cell can be recognized as „foreign” or „altered”. This leads immune cells to attack and eliminate these cells.

CD47 molecules do not differ as much from person to person as MHC class I molecules do. They have a relatively conserved structure in most individuals, meaning there are fewer variations. This conservation is important because CD47 plays a fundamental role in immune regulation and cell interaction.

For this reason, a blood transfusion generally works more smoothly than an organ transplant. In a blood transfusion, only a few antigens (such as blood group characteristics) need to be considered, while in an organ transplant, there is a high variability in MHC class I molecules, which can trigger a strong immune response.

c) SELF-Marker: Sialic Acid

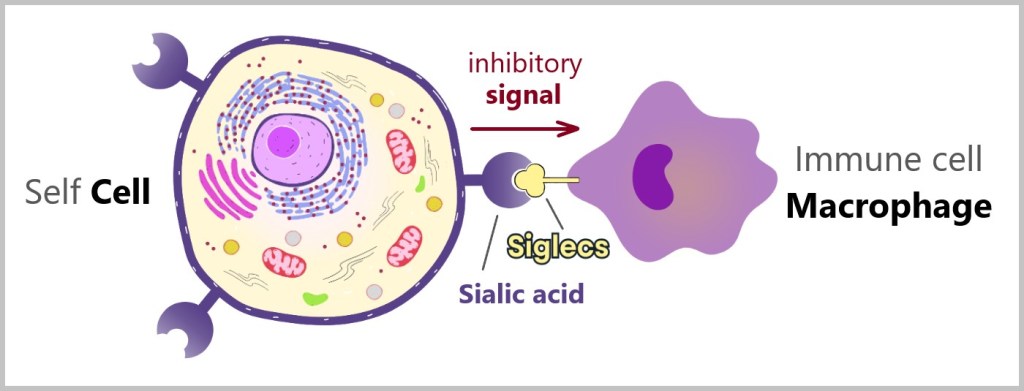

Another significant SELF-marker on the cell surface is sialic acid. Sialic acids are a group of sugar molecules found on the surfaces of cells and play an important role in cell-to-cell communication. All of the body’s own cells carry sialic acid on their surface.

Special receptors on the surface of immune cells can recognize and bind to sialic acids. These sialic acid-binding receptors are known as Siglecs (sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectins). When sialic acids bind to Siglecs, they send inhibitory signals into the immune cell, preventing it from attacking the cell. This mechanism protects the body’s own cells from attacks by the immune system.

Combination of these SELF-markers

A cell can carry MHC molecules, CD47, and sialic acid simultaneously on its surface. Each of these molecular groups serves an important function in marking the cell as self and protecting it from unnecessary immune responses. While MHC primarily serves the purpose of antigen presentation, CD47 and sialic acid ensure that cells are not attacked or eliminated by immune cells. Thus, these markers work together to efficiently regulate the immune system.

5.3. The Nonspecific Immune Defense

Our immune system continuously monitors the body for the presence of foreign substances and cell changes. As soon as something is recognized as a threat, the defense response is initiated. The nonspecific immune response is particularly fast, becoming fully activated within minutes to a few hours.

This form of immune defense is not specialized for specific pathogens. „Nonspecific” means that a general standard response occurs to every recognized threat; pathogens are fought in the same way regardless of their type. The nonspecific immune system is present at birth, which is why it is also referred to as the natural or innate immune system. In the first step, the organism attempts to prevent or at least hinder the invasion of pathogens.

I – First Line of Defense: Mechanical and Chemical Barriers

II – Second Line of Defense: White Blood Cells

5.3. a) Granulocytes

5.3. b) Macrophages

5.3. c) Dendritic Cells

5.3. d) Natural Killer Cells

I – First Line of Defense: Mechanical and Chemical Barriers

The first line of defense in our body against pathogens consists of mechanical and chemical barriers.

Mechanical barriers

Mechanical barriers include the skin and all mucous membranes. The skin, the boundary between the inside of the body and the outside environment, is our body’s most important defence against pathogens. It consists of several layers that prevent the penetration of pathogens. The outermost layer, the epidermis, renews itself regularly. Dead skin cells are constantly shed and replaced by new cells. This renewal process helps to remove microorganisms adhering to the skin.

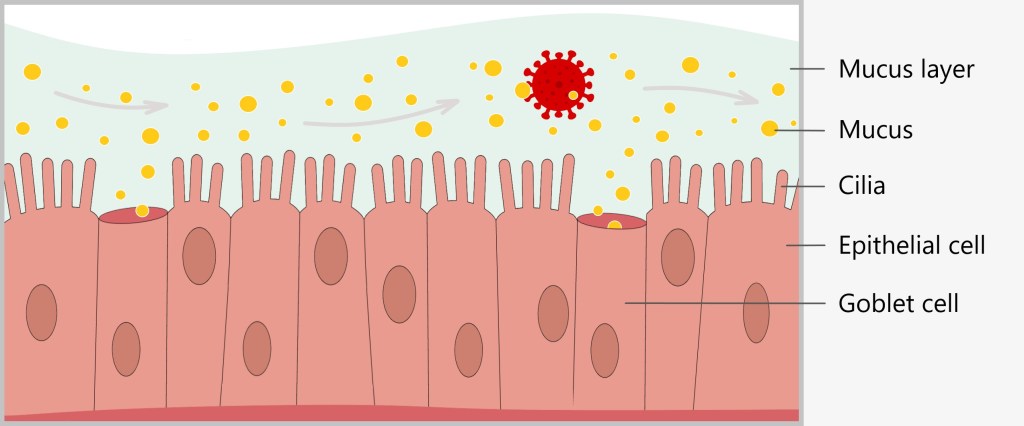

Mucous membranes are found in many areas of our body, including the nose, mouth, throat, lungs and digestive tract. They produce mucus, a sticky substance that traps and removes pathogens. For example, the mucus in our nose traps dust and microorganisms that we breathe in, preventing them from entering our lungs.

Mucosal cells have many cilia, which lie next to each other like a dense lawn. Goblet cells constantly produce mucus that surrounds the cilia and covers the surface of the mucous membrane. Foreign particles such as viruses, bacteria or dust easily become trapped in this viscous layer of mucus.

The cilia move in a wave-like manner to transport foreign particles trapped in the mucus out of the airways. Similar to a conveyor belt, the cilia push the mucus layer, along with the foreign bodies, towards the throat. There, the secretions can be expelled through sneezing or coughing, or swallowed. This self-cleaning mechanism is constantly active, ensuring that the respiratory tract remains clear of harmful substances and pathogens.

Chemical barriers

In addition, chemical substances such as acids, enzymes, or mucus hinder the attachment of pathogens. Certain areas of our body, such as the skin and the stomach, have an acidic environment. This acidic milieu is unfavorable for many microorganisms and can inhibit their growth or kill them. Particularly in the acidic environment of the stomach, many pathogens are rendered harmless.

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. Some enzymes in our body, such as lysozyme found in our saliva and tears, can break down bacterial cell walls, thus killing them. As mentioned earlier, our mucous membranes produce mucus that traps pathogens. However, mucus also serves as a chemical barrier. It contains antimicrobial substances such as immunoglobulins, which can neutralize pathogens.

Although the mechanical and chemical barriers of our body are highly effective in preventing the entry of pathogens, some pathogens can still overcome these barriers. Once pathogens have breached these initial defenses, our body activates another line of defense.

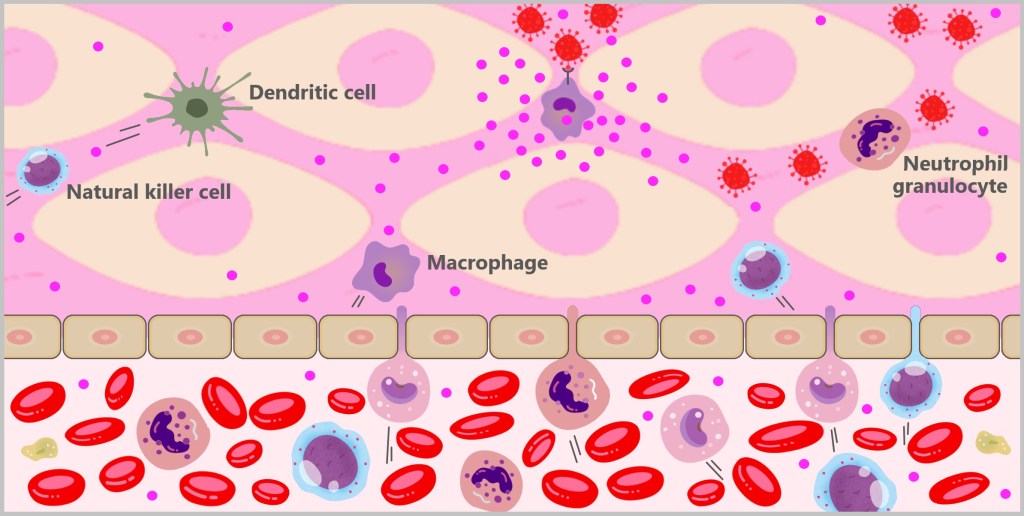

II – Second Line of Defense: White Blood Cells

If the pathogens manage to overcome the first line of defence and enter the body, they do not go unnoticed for long. Specialised immune cells such as granulocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and natural killer cells are ready to defend the body. These cells belong to the white blood cells, the leukocytes.

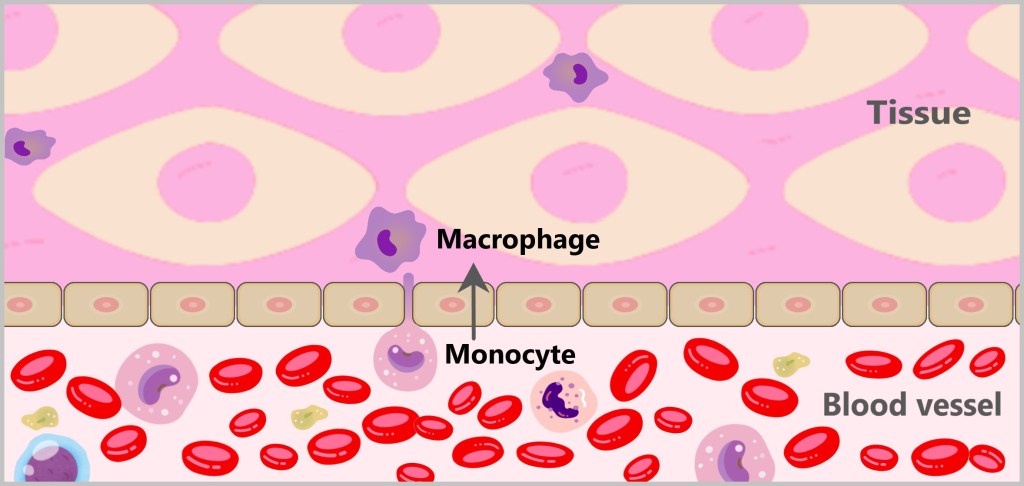

Granulocytes, monocytes, and natural killer cells circulate in the blood and migrate into tissues when needed. When monocytes enter the tissues, they develop into macrophages or dendritic cells, which then reside in the tissue and carry out their immune functions.

5.3. a) Granulocytes

Granulocytes are a subgroup of white blood cells distinguished by their characteristic granules – small, grain-like structures in the cytoplasm. These granules contain various substances that are released during immune defense and other processes. The granulocytes include neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, each of which plays distinct roles in the immune system, particularly in fighting infections and managing allergic reactions. In this description, we will focus on neutrophils, as they make up 50-70% of leukocytes in human blood, making them the most abundant immune cells.

Neutrophils, also known as neutrophil granulocytes, continuously circulate in the bloodstream and are among the first immune cells to respond to an infection. When pathogens invade the body, chemotactic signals are released, attracting neutrophils to the site of infection. In response, they exit the bloodstream and migrate into the tissue, where they can reach the infection site within minutes.

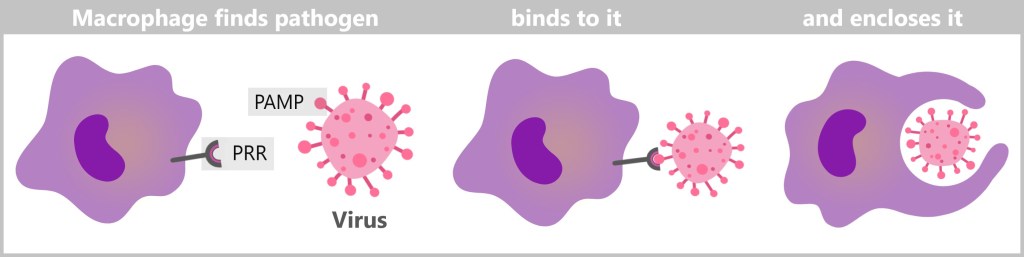

On-site, neutrophils identify pathogens using their pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which detect specific pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present on invaders like bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Their PRRs also recognize damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are released by damaged or stressed cells. This dual recognition allows neutrophils to respond not only to invading pathogens but also to cellular damage within the body.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are a key component of the innate immune system. They are responsible for the rapid detection of pathogens and cell damage, triggering an immediate immune response. PRRs recognize specific molecular patterns associated either with pathogens or with cell damage. This recognition allows the immune system to quickly identify and respond to potential threats.

These molecular patterns are divided into two main categories:

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs): These molecules are typical for microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites, but not for human cells.

Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs): These molecules are released by stressed or damaged cells and signal a danger to the organism.

PRRs can be divided into different classes, each of which specialises in different types of PAMPs and DAMPs:

Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

TLRs are specialized sensors located on the surface of immune cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils, as well as within their internal compartments. TLRs recognise a wide range of PAMPs:

TLR1 and TLR2: These two often work together and recognise certain molecules on the surface of bacteria.

TLR3: This receptor recognises viral RNA, i.e. the genetic material of viruses.

TLR4: It recognises lipopolysaccharides, which occur on the surface of many bacteria.

TLR5: This receptor recognises flagellin, a protein found in the flagella of bacteria.

TLR6: Often works together with TLR2 and also recognises molecules on bacteria.

TLR7 and TLR8: Both recognise viral RNA, similar to TLR3.

TLR9: It recognises DNA from bacteria and viruses that exhibit certain patterns.

NOD-like receptors (NLRs)

NLRs are intracellular receptors found in the cytoplasm of cells. They act like tiny sensors, constantly scanning for signs of infection or cellular damage. These receptors detect specific molecules either originating from pathogens, such as bacteria, or from within our own cells when they are stressed or damaged.

RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs)

RLRs are also intracellular receptors that are localised in the cytoplasm of cells. They are specialised in recognising viruses that have entered the cell.

C-type lectin receptors (CLRs)

CLRs are located on the cell surface of immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. They recognise certain sugar structures (carbohydrates) on the surface of pathogens, particularly fungi.

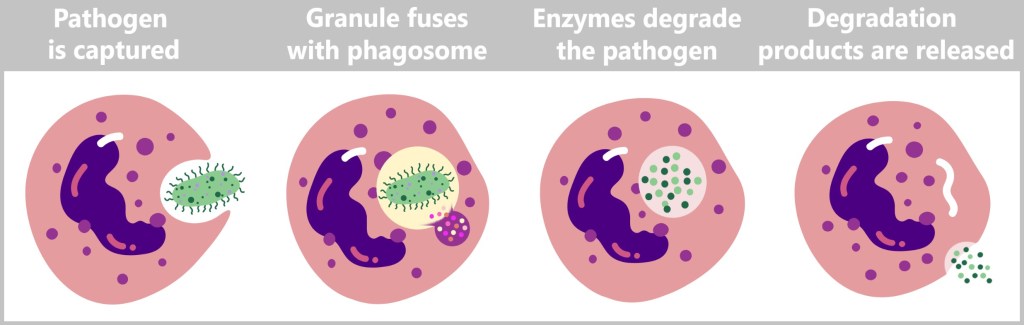

Neutrophil granulocytes eliminate intruders or diseased cells by engulfing and destroying them. They encapsulate the pathogen in a membrane-bound vesicle called a phagosome. After ingestion, the granules of the neutrophils fuse with the phagosome. These granules contain enzymes and antimicrobial substances that degrade and kill the enclosed pathogen. The remaining breakdown products that cannot be reused are then released from the neutrophils. These remnants can be taken up and further processed by other immune cells, such as macrophages.

In addition, neutrophils also eliminate damaged tissue cells. This entire process, in which cells engulf and degrade foreign bodies and damaged cells, is referred to as phagocytosis.

The term phagocytosis originates from Greek and consists of two parts: phagein, meaning „to eat” or „to engulf”, and kytos, meaning „cell” or „container”. Thus, the term „phagocytosis” literally describes „cell-eating” or „engulfing by cells”. For this reason, cells that perform this function are also referred to as phagocytes.

Neutrophils have a relatively short lifespan and often die after phagocytosis and digestion of pathogens. This process, called apoptosis (programmed cell death), helps to regulate the inflammatory response.

When many neutrophils die in an infected area, their remains accumulate along with the digested pathogens and cellular debris. This accumulation of dead cells and degradation products forms pus. Pus is a viscous, yellowish or greenish fluid that is often found in infected wounds or abscesses. Apoptotic (dead) neutrophils are also absorbed and digested by macrophages, cleansing the surrounding tissue and promoting healing.

In some cases, neutrophils release net-like structures consisting of DNA and antimicrobial proteins. These NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps) trap pathogens and kill them by preventing their movement and replication.

This short animated video shows very nicely how neutrophils work.

Neutrophils work closely with other immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells by releasing signalling molecules. These signalling molecules, such as chemokines and cytokines, recruit and activate other immune cells to the site of infection. Neutrophils thus make a significant contribution to the inflammatory response. Their rapid response and ability to effectively combat pathogens makes them a crucial component of the innate immune response.

5.3. b) Macrophages

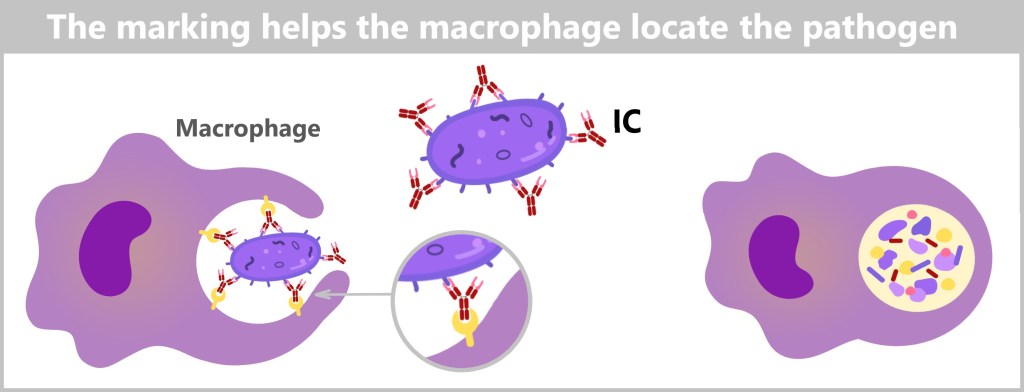

Macrophages are large phagocytic cells, with their name derived from the Greek word ‚macro‘ meaning large and ‚phage‘ meaning eater. There are different types of macrophages.

Resident macrophages are firmly anchored in the tissues. Recruited macrophages arise from the monocytes circulating in the blood. When monocytes come into contact with cytokines (signaling molecules), they migrate from the blood into the tissue and differentiate into macrophages there. Once in the tissue, they often remain stationary while patrolling for pathogens and dead cells.

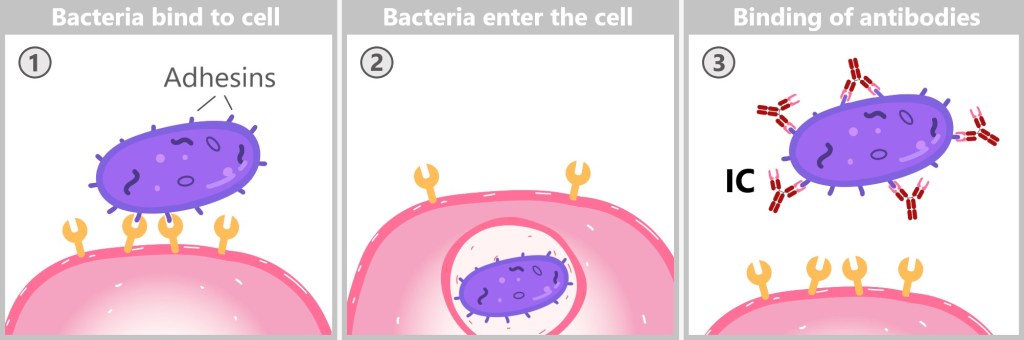

Macrophages recognize pathogens through specific proteins on their surface called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). These surface proteins of pathogens fit into the pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of macrophages like a key fits into a lock. Similarly, cell debris or dead cells produce specific „eat-me” signals, which are recognized by macrophages in the same way. Once the pathogen or cell debris is identified, the macrophage binds to it, envelops it with its flexible membrane, and initiates phagocytosis.

During phagocytosis, the macrophage absorbs the pathogen or cell debris by invagination and forms a membrane-enveloped vesicle, the phagosome. This phagosome fuses with a lysosome to form a phagolysome. In the phagolysome, the ingested particles are broken down by the digestive enzymes of the lysosome. Here you can see macrophages in action.

Phagocytosis is an ancient mechanism dating back to unicellular eukaryotes such as amoebae and provides a vivid example of how the immune system has evolved over millions of years.

Phagocytosis: an ancient survival mechanism

Phagocytosis is a good example of how the immune system has developed over millions of years.

The history of phagocytosis goes back a long way and is closely linked to the evolution of life. Single-celled organisms such as amoebae have been using phagocytosis to ingest food for more than 100 million years. To detect their food, they have receptors that react to specific chemical substances released by bacteria or other potential food sources. Amoebae move towards these signals through a process called chemotaxis. They then enclose their prey with their cell membrane and form so-called food vacuoles in which digestion takes place.

Amoebae are therefore excellent examples of the early users of phagocytosis. They are ancient life forms that are simple in their structure but very effective in their function. The phagocytosis mechanism may even have served evolutionarily as the basis for the cell fusion process that eventually led to the emergence of the eukaryotic cell, which made more complex organisms possible.

Sources:

The Origins of Phagocytosis and Eukaryogenesis

The Endosymbiotic Theory

Discovery by Ilya Metschnikow

The actual term ‘phagocytosis’ was first coined at the end of the 19th century by the Russian biologist Ilya Metschnikow, who is regarded as a pioneer of immunobiology. During a stay in Italy, Metschnikow carried out studies on starfish and observed how certain cells devoured pathogens or foreign particles. He called these cells ‘phagocytes’ (Greek: ‘scavenger cells’), and the process itself he termed ‘phagocytosis’. For this discovery, Metschnikow was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1908.

Evolution of phagocytosis in the immune system

Over the course of evolution, phagocytosis has evolved from a mechanism for nutrient uptake into a central component of the immune system. Immune cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils in the innate immune system have refined the process of phagocytosis, using it not only to recognize, engulf, and destroy pathogens but also to communicate with other immune cells.

The „parading” of antigens on the cell surface is a true evolutionary trick: immune cells present fragments of digested pathogens (antigens) to alert other immune cells. While amoebas simply digest their prey, immune cells have learned to turn this into a „message” for the body!

Macrophages mainly concentrate on „eating” pathogens and „cleaning up” cell debris. However, this also gives rise to the possibility of antigen presentation.

During degradation, smaller fragments are released, including potential antigens, which are bound to MHC class II molecules and presented on the cell surface. This antigen presentation is crucial for the activation of other immune cells, especially T cells. The antigen-MHC II complexes are presented to the T cells, which then initiate the specific immune response – a process that we will discuss in more detail in the following sections.

Many other smaller molecules produced by the digestive process, such as amino acids, sugars and lipids, can be re-utilised by the macrophage as nutrients.

Other waste products and indigestible residues are packed into vesicles and excreted from the cell. This prevents the accumulation of waste within the macrophage and allows it to continue working. Some of the indigestible residues can ultimately be removed via various excretory processes of the body, such as urine, faeces or sweating. This occurs after further degradation and transport through the lymphatic system or the bloodstream to the corresponding organs such as the kidneys or intestines.

Macrophages are very efficient phagocytes and can ingest and degrade a large number of pathogens and cellular waste. Within a few hours, one macrophage can phagocytise hundreds of bacteria.

As not just one pathogen usually invades the body, macrophages call on other immune cells for help. To do this, they secrete cytokines that strengthen the immune response.

Cytokines cause the blood vessels around the site of infection to dilate, leading to increased blood flow. This enhanced circulation allows more immune cells, oxygen, and nutrients to reach the affected area. As a result, swelling (edema) occurs in the tissue, which also explains the redness and warmth often associated with inflammation.

As the immune response progresses, macrophages initiate the healing process by releasing growth factors that promote cell division and differentiation.

Macrophages play a central role in the immediate immune defense. Their primary tasks are fighting and eliminating pathogens, as well as clearing cellular debris through phagocytosis. To accomplish this, macrophages possess around 60 different types of receptors, enabling them to recognize a wide variety of pathogens. Additionally, they perform antigen presentation to support the specific immune response, though this is more of a supplementary function. In contrast, dendritic cells are more specialized in collecting and presenting antigens, with their primary role being the activation of the adaptive immune response.

5.3. c) Dendritic Cells

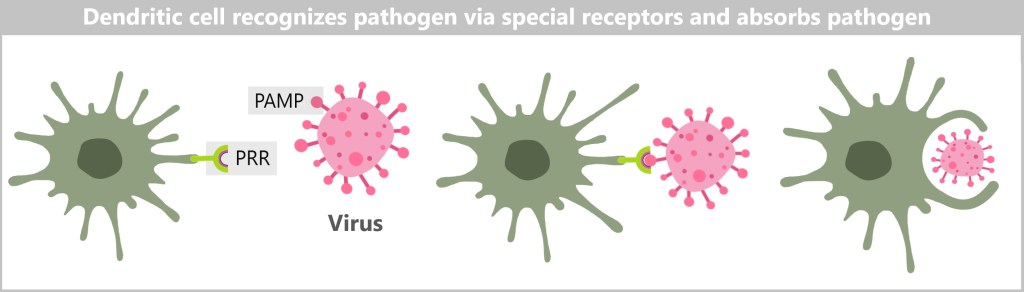

Dendritic cells are specialised immune cells that play a key role in triggering the specific immune response. The name is derived from their numerous, branched projections, which are reminiscent of the dendrites of nerve cells.

Dendritic cells originate from precursor cells in the bone marrow and further differentiate in tissues. They are found in almost all tissues of the body, especially at the interfaces with the external environment, such as the skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract, where they continuously search for antigens. In tissues, they can develop into different subtypes, each of which has specific roles in recognizing and presenting antigens.

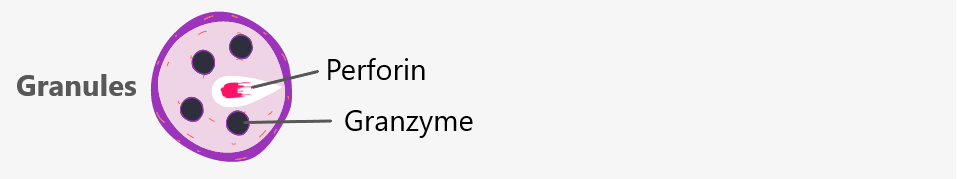

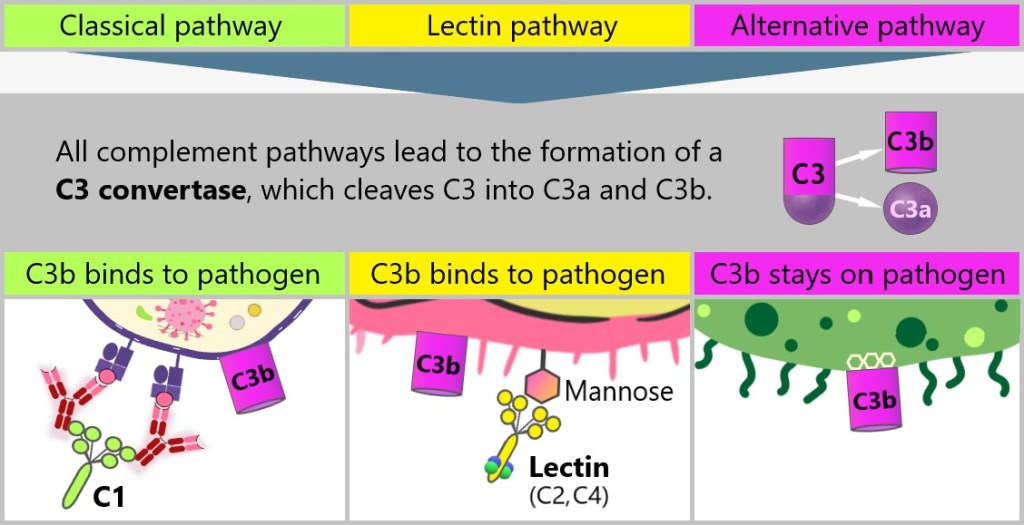

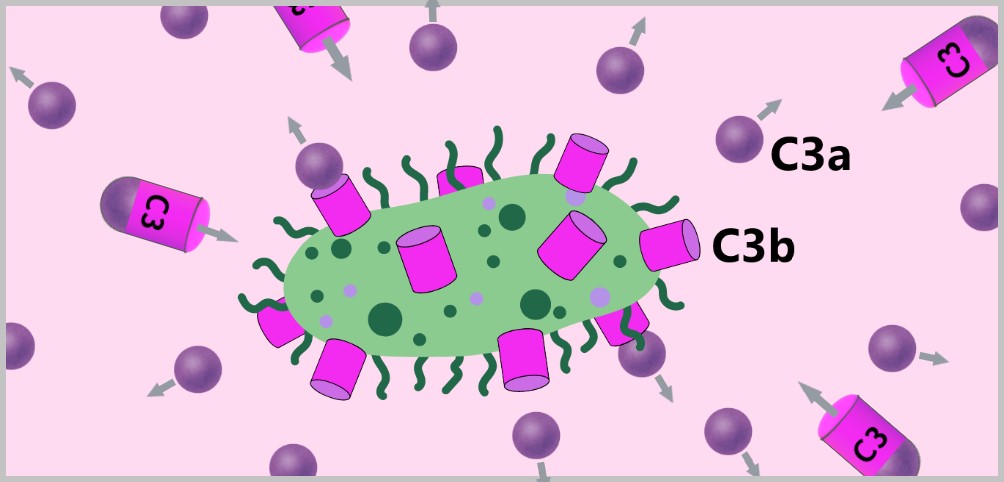

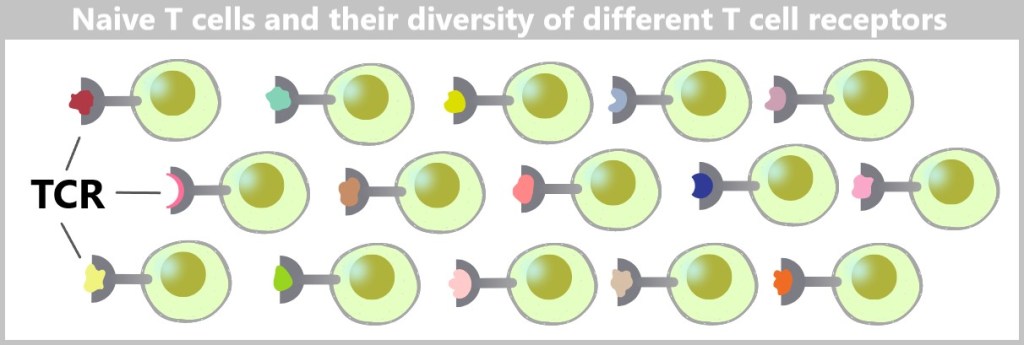

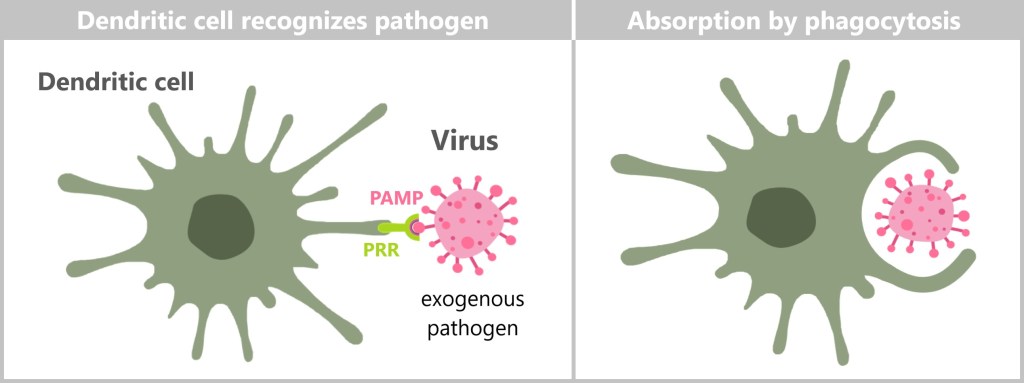

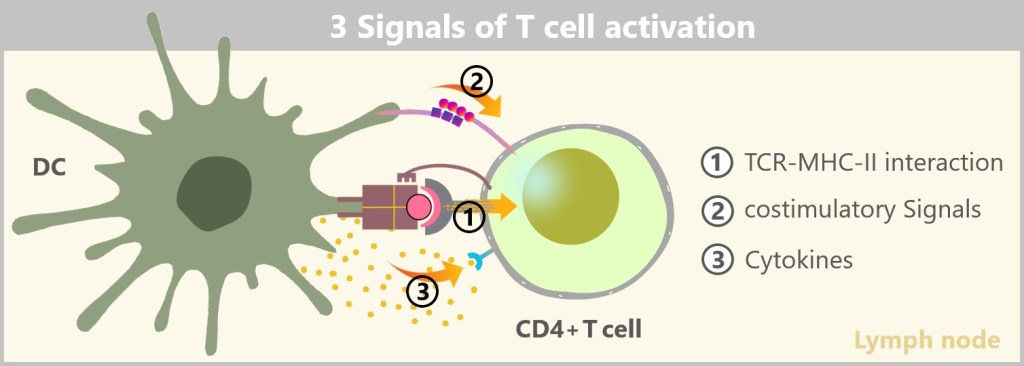

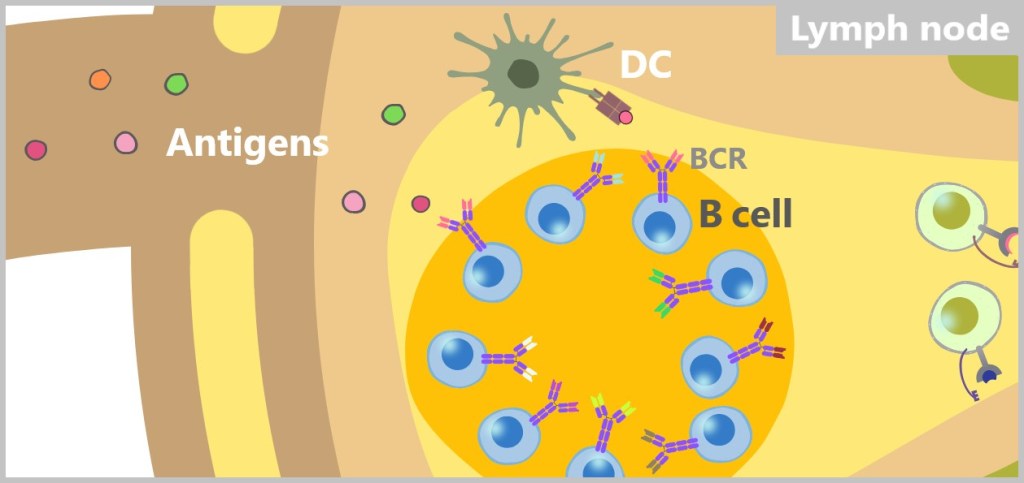

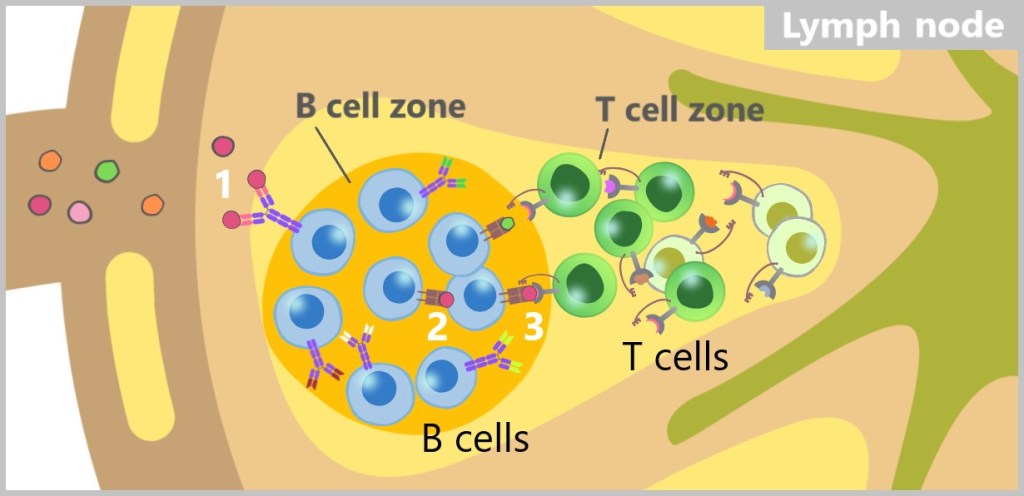

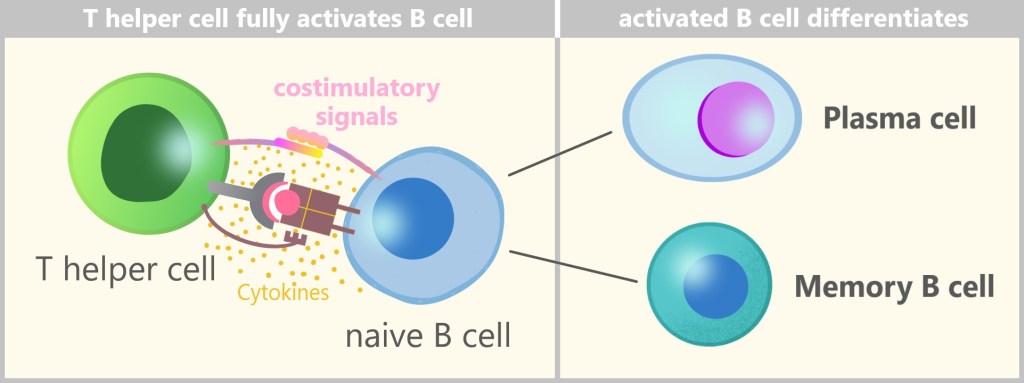

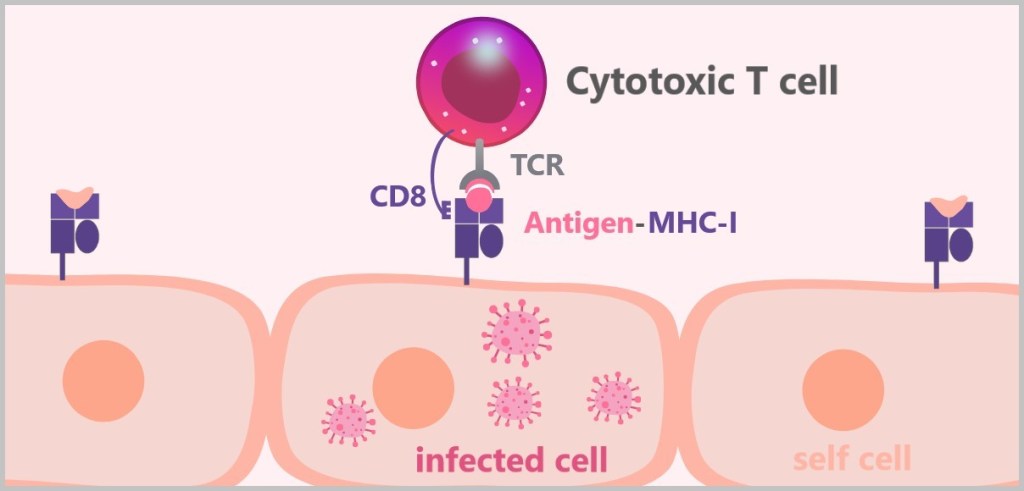

Dendritic cells recognise pathogens and foreign substances through special receptors on their surface, the so-called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). These receptors bind to characteristic molecular patterns on the pathogens, which are known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Damaged or dead cells also send out specific „eat-me” signals that are recognised by the dendritic cells.