The Art of Governing

If you ask ChatGPT impartially about associations with the term „Smart Governance” and request a satirical description, you might get the following suggestion:

„Smart Governance is the visionary concept that makes us believe we live in a perfect symbiosis of technology and administration, while in reality we are trapped by an invisible web of algorithms, data streams and bureaucratic surveillance. Imagine a world in which your decisions are no longer made by you, but by an AI that knows exactly what you want – before you do.

In the era of smart governance, friendly, omniscient AIs monitor your every move. These well-meaning digital shepherds are always ready to tell you when it’s time to get up, when you should go to work and whether your jogging route is particularly efficient today – all in the name of your productivity and health, of course.

Forget the freedom to make spontaneous decisions. Your to-do list is maintained by an almighty algorithm that optimizes every aspect of your life. Why think about what you want for dinner when smart governance has already calculated the perfect meal plan for you?

In this utopian world of smart governance, there are no secrets. Your data is openly accessible because transparency is key. From your financial transactions to your latest doctor visits, everything is public to ensure everyone is on the same page. After all, why would anyone have anything to hide?

Your behavior is constantly corrected by subtle hints (nudges). Do you want to eat the last chocolate in the cupboard? A gentle hint on your smartphone will alert you to the fact that you have already reached your calorie limit. In this way, you learn to always make the „right” decisions without the burden of thinking.

Your opinion counts – at least in theory. Automated systems take the effort out of voting by deciding on the basis of your previous preferences. After all, the AI has a better understanding of your needs and wishes than you do.

Smart governance is the triumphant evolution of the transparent citizen, in which you no longer have to worry about making your own decisions. In this satirical vision of the future, you are no longer the master of yourself, but a well-supervised subject in a perfectly organized digital paradise. All for the higher goal of efficiency and optimization – welcome to the smart world of tomorrow!“

Before we dive into the wonderful world of smart governments, let’s first clarify the basic terms. And don’t worry, it won’t be as complicated as a politician trying to answer a simple question!

The term „smart” has undergone a fascinating development. It originally comes from the Old English „smeart” and meant something like „painful” or „stinging”. Yes, you read that right – if you were stung by a wasp back then, you would have said: „That was smart!” Nowadays, however, „smart” means something completely different. It stands for cleverness, efficiency and technology – much like your smartphone, which is smarter than some politicians!

Let’s move on to the next term ‚governance‘. This comes from the Latin and means something like ’steering‘ or ‚directing‘. It is therefore about the art and science of leading a society, making decisions and maintaining order. Think of governance as a big chess game in which the citizens are the pawns – but without the risk of someone having to sacrifice the pawns.

But how does simple Governance become Smart Governance? It’s quite simple: you add technology, data analysis, and a dash of innovation. The result is a government that reacts faster, is better informed, and even reads your emails—well, of course, only in the best sense! In the world of Smart Governance, the classic question „Who rules the world?” magically transforms into „Who is the smartest in the room?”.

Governance and Smart Governance are like siblings fighting over the remote control – only this one is about control over entire nations! But let’s not forget what really binds these two siblings together: Power. Power to make decisions, power to change things, and power to decide who orders the pizza at the next cabinet meeting.

Governance and Smart Governance are the frameworks through which power is exercised, controlled, and legitimized—much like the invisible wizard behind the scenes who rules the political stage. But what does power actually mean?

Power is a fascinating force that operates within the social relationships and structures of our world. It refers to the ability of a person or group to influence or control the behavior, decisions or actions of others. Whether in politics, business, society or on a personal level, power manifests itself in many different ways and shapes our daily lives.

From political authority and social prestige to economic influence, power takes various forms and dimensions that are intertwined and shape our world in complex ways. It can be both obvious and direct as well as subtle and indirect, and it is often unevenly distributed, leading to tensions, injustice, or even conflicts.

„The feeling of having no power over people and events is generally unbearable to us. When we feel helpless, we feel miserable. No one wants less power; everyone wants more. In the world today, however, it is dangerous to seem too power hungry, to be overt with your power moves. We have to seem fair and decent. So, we need to be subdecongenial yet cunning, democratic yet devious.“

Robert Greene, POWER – The 48 Laws of Power

The urge for power is a fundamental human need. However, in a world characterized by democratic principles and human rights, the direct and overt exercise of power is often unacceptable. Instead, it requires subtle strategies and tactics to gain and maintain power while maintaining an image of fairness and decency. In a world characterized by increasing transparency and the pursuit of justice, the ability to exercise power in smart and skillful ways is critical to achieving long-term goals and bringing about change. This does not mean that ’smart governance‘ should be manipulative or unethical. On the contrary, it requires a balanced understanding of ethical boundaries and a careful balance between power and responsibility.

Michel Foucault, a significant thinker in the analysis of power structures, emphasized the ubiquity of power in social structures and interactions. He argued that power is not only exercised from top to bottom but also comes from various directions and levels. This perspective highlights the complexity and multifaceted nature of power relations and reminds us that power is not confined to specific institutions or individuals but is present in the smallest and most everyday interactions.

„Power is everywhere: not that it engulfs everything, but that it comes from everywhere.“

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality

Foucault’s ideas emphasize the importance of a comprehensive understanding of power and demonstrate that power is not only exercised through overt confrontation or visible authority but also through subtle mechanisms of normalization, discipline, and surveillance. In a world where power often operates behind the scenes, it is crucial to recognize and critically examine these hidden dynamics to achieve a more just and balanced power relationship.

In the upcoming chapters, we will first turn our attention to the theoretical foundations of power in a society and analyze its relationship with Governance and Smart Governance. We will explore how power structures are organized both formally and informally and how they are exercised through various mechanisms—political, economic, and social.

Subsequently, we will examine concrete examples such as the COVID-19 policy and the One-Health approach to illustrate different forms of governance.

Furthermore, we will highlight some key technological pillars of Smart Governance and provide an outlook on the future of this development.

Through this in-depth analysis and investigation, we aim to foster a deeper understanding of the dynamics of Power, Governance, and Smart Governance, and encourage readers to critically reflect on the ways in which power is exercised and directed in our modern world.

1. Governmentality – The Visible and Invisible Threads of Power

1.1. The Link between Knowledge and Power

1.2. Biopolitics

1.3. Dispositives of Power

1.4. Disciplinary Power

1.5. Technologies of the Self

1.6. Resistance and Counterpower

1.7. Summary

2. Corona Crisis: Governance and Biopolitics in a State of Emergency

3. One Health Approach – Prevention Through Continuous Governance

4. The Technological Pillars of Smart Governance

4.1. The European Digital ID

4.2. Technological Self-management as the Foundation of Smart Governance

4.3. Digital Twins as the Basis for Smart Governance Strategies

4.4. Intelligent Money – Smart Money and Smart Governance

5. A Glimpse into the Future – Smart Governance at Its Best

6. Smart Resistance

7. Epilogue – Is Smart Governance Truly the Only Option?

1. Governmentality – The Visible and Invisible Threads of Power

In his analysis of forms of governance and ruling in modern societies, Foucault introduces the concept of „Governmentality”. This term combines the words ‚government‘ and ‚mentality,‘ and refers to the ways in which techniques and practices of governance deeply penetrate and influence people’s thinking and behavior.

Foucault argues that governance is not merely a matter of political institutions or state authority but encompasses a complex network of knowledge, measures, and techniques aimed at steering and guiding human behavior. It involves not only the direct exercise of coercion or control but also the construction of specific systems of knowledge, norms, and behaviors that subtly influence individuals.

Governmentality surrounds us like a three-dimensional matrix. It has different faces and sometimes contradictory manifestations, so that we often „can’t see the wood for the trees”. The following classification of its most important aspects can provide a simple orientation aid in this ‚power jungle‘.

1.1. The Link between Knowledge and Power

The phrase „knowledge is power” has established itself over the centuries and is often interpreted to mean that someone with extensive knowledge also possesses significant influence and superiority over others. This notion does not always carry a positive connotation: the more one knows about a person, the more control one can exert over them and exploit their weaknesses.

In Foucault’s analysis, knowledge itself is an instrument of power, operating at both macro and micro levels. It is not neutral but is always intertwined with power processes that profoundly affect social structures and individual lives. Those who possess knowledge or control over it also wield power over others.

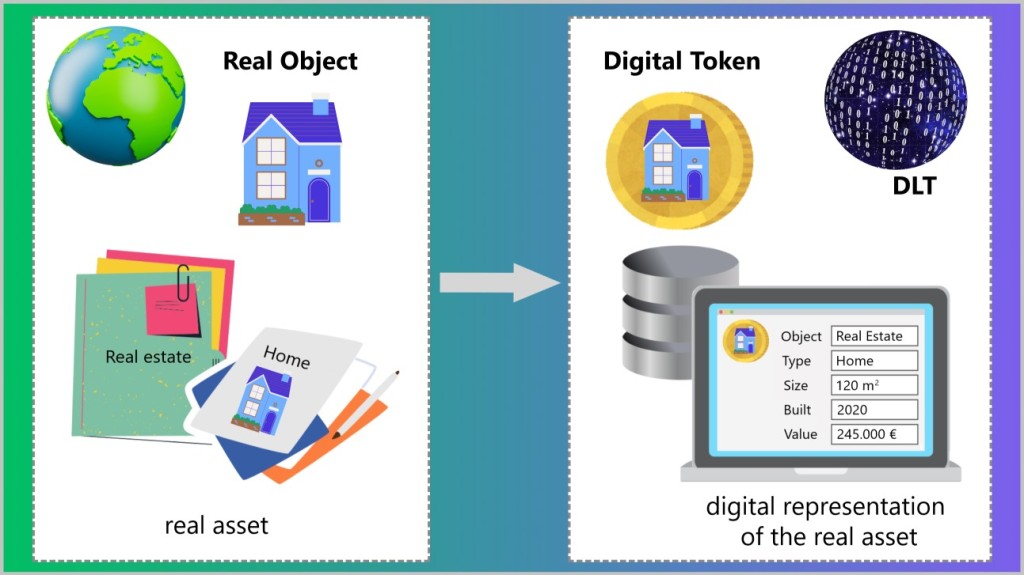

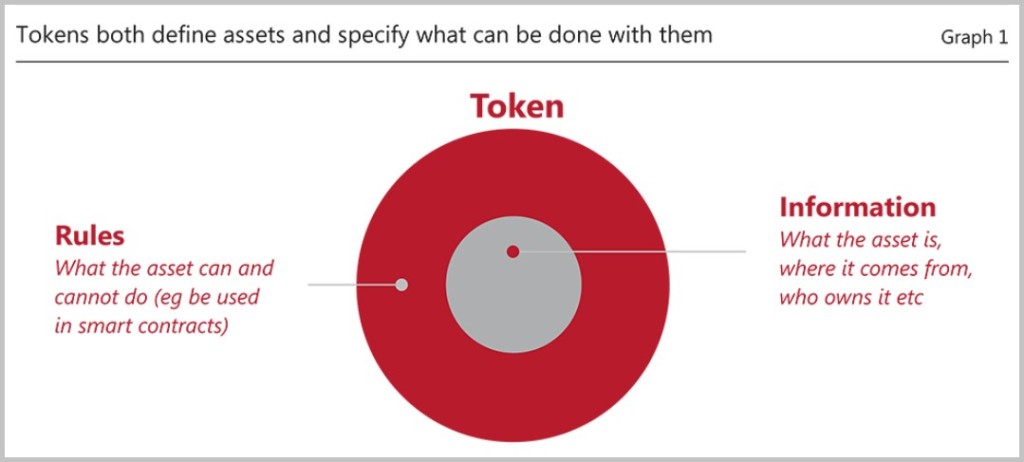

Knowledge involves understanding patterns, connections, and meanings. It is created when information is analyzed, linked, and interpreted within a coherent and useful framework. Information arises from data when the latter is placed in context and interpreted. Data, in turn, are raw pieces of information that can be collected.

The sheer volume of available data can certainly expand the possibilities for acquiring knowledge, but simply increasing the amount of data does not automatically lead to more knowledge. Instead, it is crucial how data are collected, analyzed, interpreted, and placed into a useful context. The quality of the data, the methods of analysis, and the ability to synthesize and interpret information meaningfully play a critical role in transforming data into knowledge.

The linking of knowledge and power is a key driving force behind the digitalization of modern societies. Digitization generates, collects and analyses huge amounts of data (Big Data). Big data includes information from various sources such as social media, sensors, transactions, medical records and more. Governments and companies use big data and advanced analytics techniques to collect, analyze and interpret extensive information about the population. This data often includes personal information such as demographics, behavioral patterns, consumer behavior, health data and social interactions.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being used to gain insights from these analyses. AI encompasses technologies that enable computers to perform tasks that would normally require human intelligence. Through the use of machine learning (ML), a subfield of AI that focuses on algorithms and models that enable computers to learn from data and make predictions, predictive models are being developed that can forecast future events.

The combination of big data, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) offers governments and companies new tools. They can use them to identify trends, carry out risk assessments and predictive analyses, implement monitoring programs, plan interventions, allocate resources, control social processes, make informed decisions and ultimately exercise power.

The „Link between Knowledge and Power” is ubiquitous and omnipresent.

Governments and businesses use the data they collect to implement surveillance and control mechanisms. This ranges from state surveillance aimed at combating crime and terrorism to corporate use for influencing consumer behavior and securing market share.

Big data analysis and ML can be used to carry out predictive analyses to combat epidemics, control traffic flows or plan urban infrastructure and make political decisions on this basis.

By collecting and analyzing health data (electronic patient records, health apps, genetic data), health authorities and institutions can take more precise and effective measures for preventive and curative healthcare. These measures can also be used to monitor and manage health behavior (e.g. vaccination campaigns, quarantine measures, etc.).

In the education sector, data on student performance and behavior are collected and analyzed to develop educational strategies tailored to the individual needs of students. This not only impacts education policy but also influences the future opportunities and prospects of the students.

Companies use data analysis to increase productivity and efficiency, optimize work processes and monitor and control employee behavior.

Platforms like Facebook, Google, and Amazon collect extensive data on their users and use it to provide personalized content and advertising that influences and directs user behavior. These platforms hold immense power due to the knowledge derived from the data of their billions of users. They can shape public opinion, influence purchasing decisions, and even promote or hinder political movements.

As a central aspect of governmentality, the connection between knowledge and power is put into practice through Smart Governance.

1.2. Biopolitics

A fundamental component of governmentality is biopolitics, which deals with the comprehensive management of the population by state and other institutions. It encompasses many aspects of human behavior and social life. This includes measures related to healthcare, social policy, and demographic statistics, as well as other state interventions that impact the life and well-being of the population. Biopolitics further covers important areas such as reproduction and family policy, nutrition and consumption, education and upbringing, work and employment, environmental protection and sustainability, security and surveillance, migration and citizenship, as well as sexuality and gender politics.

Through the introduction of laws, policies, and standards, biopolitics manages and regulates the life of the entire population in all its aspects. With these comprehensive measures, biopolitics aims to steer the behavior of the population and achieve specific societal goals.

Here are a few specific examples:

In the realm of healthcare, many countries have laws that mandate certain vaccinations to prevent the outbreak and spread of infectious diseases. For example, the Measles Protection Act requires measles vaccinations for children in daycare centers and schools, as well as for employees in medical facilities and community centers.

Other laws and measures serve to control and contain epidemics, such as the Infection Protection Act (IfSG) in Germany. This legislation regulates measures for the prevention and control of infectious diseases in humans, establishing quarantine protocols and reporting requirements.

Through compulsory education, curricula, and educational standards, education systems are used not only to impart knowledge and skills but also to promote social norms and values considered crucial for the stability and progress of society.

Food production guidelines, nutritional standards or programs to combat obesity are used to regulate nutrition and consumption. This allows governments to influence the health and behavior of the population in order to achieve certain health or economic goals.

Through environmental laws and standards, governments can regulate the behavior of individuals and businesses to achieve long-term ecological goals.

Immigration laws can regulate migration and influence the determination of citizenship as well as the demographic composition and cultural dynamics within a state.

Laws concerning equality, LGBT rights, and sexual education, which address sexual orientation and gender identity, have profound impacts on social norms within society.

etc.

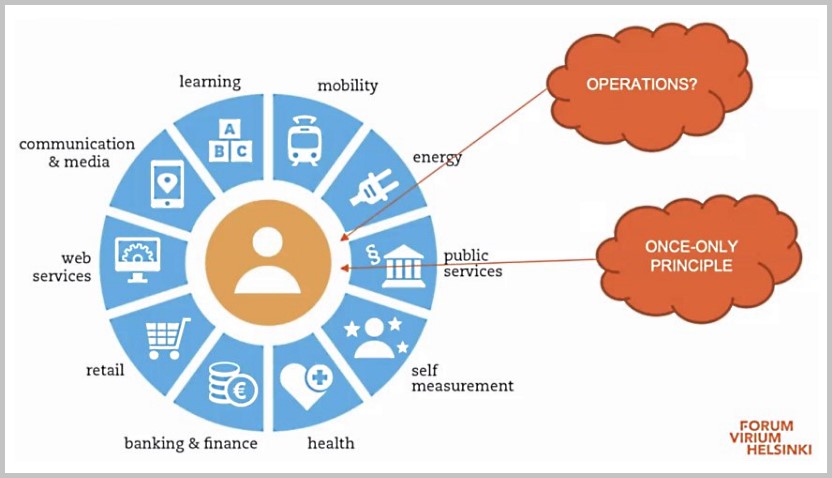

Through the advancing digitalization of nearly all aspects of societal life, new terms such as Smart Health, Smart Cities, Smart Economy, etc., are continuously defined. The power generated through knowledge is concretely and perceptibly implemented in daily governance and administration through biopolitical measures.

The realization of biopolitical strategies and goals requires corresponding infrastructure and mechanisms. This brings us to the so-called dispositives of power.

1.3. Dispositives of Power

Dispositives are networks of various elements such as institutions, laws, regulations, administrative measures, and scientific discourses that work together to achieve specific societal goals. These networks create and implement the frameworks within which power is exercised.

Biopolitics operates within and through the dispositives of power. The networks that constitute these dispositives are the structures through which biopolitical strategies are implemented. For instance, biopolitics utilizes institutions such as hospitals, social services, schools, media, businesses across various industries, and prisons—all of which are components of the dispositives of power.

Dispositives of power represent the means and mechanisms through which biopolitical measures are coordinated and implemented. A dispositif for public health, for example, might include hospitals, health laws, vaccination campaigns, and medical research, all working together to achieve the health objectives of biopolitics.

Dispositives of power enable the normalization and control of populations. Biopolitics aims to promote certain norms and behaviors, and the dispositives create the frameworks within which these norms and behaviors are established as „normal” and „desirable”. Dispositives integrate various elements of society and create an environment in which certain behaviors are encouraged while others are discouraged.

This shapes and directs people’s behavior in subtle and often invisible ways. Instead of overt coercive measures, the dispositives use knowledge systems, discourses and institutional practices to influence people’s behavior.

The practical implementation is usually as follows:

Carefully organized collections of knowledge and information, such as scientific studies and news reports, can provide the foundations upon which people base their views and decisions. (When people are informed through scientific studies that vaccinations can prevent diseases, they are more likely to be willing to get vaccinated.)

These can be combined with conversations and discussions in society about specific topics. These conversations take place in the media, in politics and in everyday life. These discourses shape people’s opinions and attitudes. (The way the media presents issues influences public opinion. When the media frequently report on the dangers of climate change, public awareness increases and people are more willing to make environmentally friendly decisions, such as reducing plastic waste or using public transportation.)

In most cases, these actions lead to the introduction of rules and norms to which people must adhere. (By implementing vaccination programs and preventive health check-ups in hospitals and clinics, the population is regularly encouraged to undergo check-ups and vaccinations.)

Smart governance can be seen as a modern expression of the dispositives of power that extends and deepens traditional concepts of regulation, standardization and surveillance through state-of-the-art technologies and data analysis.

A dispositive can include disciplinary power as one of the methods of exercising power.

1.4. Disciplinary Power

While biopolitics focuses on the management of populations, disciplinary power focuses on the regulation of individuals. Both forms of power aim to control and optimize people’s behavior. While biopolitics operates at the macro level by regulating the conditions and circumstances of the entire population, disciplinary power intervenes at the micro level by shaping the bodies and behaviors of individuals. Both forms of power complement each other and create a comprehensive system of social control.

Disciplinary power is exercised through surveillance, standardization, punishment and reward, education and training. It aims to discipline individuals, standardize their bodies and behaviors and make them productive.

Most of you will likely first think of prisons and penal systems. Indeed, the criminal justice system in democratic societies relies on disciplinary power to sanction and correct deviant behavior. Prisons and correctional facilities are institutions where surveillance, punishment, and rehabilitation play a central role.

However, most of us encounter disciplinary power much more frequently than we might realize.

Schools are a classic example of institutions that exercise disciplinary power. Through curricula, class rules, exams and monitoring systems, students are encouraged to behave according to norms and achieve certain performance standards.

Employers use disciplinary power to control and direct the behavior of their employees. Through employment contracts, employee appraisals, workplace monitoring and reward/punishment systems, employers can influence the productivity and compliance of their employees.

In democratic societies, various social control mechanisms exercise disciplinary power. These include social norms, moral expectations, cultural values, and peer pressure, which influence and regulate people’s behavior. Peer pressure refers to the influence that peers can exert on a person’s behavior, attitudes or decisions. This influence arises from the desire to be accepted, liked or respected by the group.

The media also play a crucial role in exercising disciplinary power. Through targeted reporting, advertising, and entertainment formats, they can propagate, promote, and support certain norms, values, and behaviors, thereby steering moral expectations or peer pressure on individuals in one direction or another.

Finally, it is important to recognize that the system of punishment and reward affects psychological behavior. It transforms the rules of the system from something one must follow to something one wants to follow because it is in one’s own interest. This philosophy underpins „technologies of self-management”, which rely on motivational systems to encourage desired behavior. By skillfully combining positive and negative incentives, these technologies help individuals to self-regulate and achieve personal as well as societal goals.

1.5. Technologies of the Self

Technologies of self-management, or „Technologies of The Self”, refer to the methods and practices individuals use to regulate, shape, and control themselves. This can involve self-discipline, reflection, self-improvement, and other personal strategies aimed at meeting specific norms.

The legal and normative frameworks established by ‚biopolitics‘ and ‚dispositives of power‘ for collective governance and regulation influence individual behavior and self-image. Through technologies of the self, people internalize these norms, voluntarily and consciously adapting their behavior because they perceive the rules as useful and beneficial for themselves.

Fitness apps rely on positive reinforcement through rewards and challenges to motivate users to exercise regularly. Learning platforms offer rewards for completing modules or passing tests, increasing motivation to keep learning. Financial apps offer incentives for sticking to budgets and saving money, while highlighting negative consequences for overspending. Self-management methods such as the Eisenhower Principle or the Pomodoro Technique encourage people to use their time efficiently and focus on important tasks.

In this way, external directives become internal motivations.

1.6. Resistance and Counterpower

Some of you may be irritated or disturbed by the theoretical classification of the most important aspects of governmentality. But according to Foucault, power and resistance are closely linked. Where there is power, there is also the possibility of resistance. Resistance does not arise from outside or independently of power, but is part of the relationship between the actors of power themselves.

„Where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently, this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power.“

In Defence of Foucault: The Incessancy of Resistance

Power relations can only exist if there are points of resistance that oppose them. Resistance is always a part of the network of power, serving as an adversary, target, support, or entry point for power. There is not just one grand locus of resistance, but many individual resistances, which do not necessarily overcome power in its entirety. Thus, wherever there is power, the possibility of resistance exists. Resistance does not come before or after power; rather, both exist simultaneously and condition each other.

These considerations reflect the dynamic between conformity and non-conformity in society. It illustrates that a small group of non-conforming individuals plays a significant role in promoting change and innovation, while the conforming majority contributes to stability and order.

Conformity and non-conformity are not rigid categories, but rather dynamic concepts that depend heavily on the social context and individual circumstances. What is considered conforming or non-conforming in one situation may be different in another. These concepts exist on a continuum, and a person’s behavior can move between these two poles depending on the circumstances.

Foucault viewed resistance as specific struggles against the everyday applications of power, rather than a struggle against the existence of power itself. Since power relations are deeply embedded in social structures and cannot be simply eradicated, they cannot be radically abolished. Resistance, therefore, manifests in various forms and practices that challenge and negotiate the ways power is exercised and experienced, rather than aiming to eliminate power entirely.

The interaction between governance and resistance is a dynamic and complex process that takes place in various ways.

When governments encounter resistance, they can compromise or make concessions to make their measures more acceptable and reduce resistance. By involving the leaders of the resistance or including certain demands in their programs, governments can not only mitigate the resistance but also integrate it into their own strategy.

Governments can use certain discourses to present their measures as necessary or beneficial in order to increase acceptance among the population. At the same time, they can portray resistance movements as illegitimate, irrational or dangerous in order to reduce their influence.

Modern technologies such as Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) offer governments new opportunities to monitor and analyze resistance. By analyzing data, they can identify potential resistance movements at an early stage and react accordingly. Using predictive models, governments can predict potential resistance patterns and take proactive measures.

Resistance and counterpower function as feedback mechanisms within power structures. They indicate to governments and institutions where tensions and discontent exist and can lead to adjustments in governance strategies. Persistent and significant resistance can compel governments to implement political reforms or reconsider existing measures. Resistance movements can initiate important public debates, contributing to the formation of new norms and values, which then influence governance strategies.

The constant interaction between power and resistance can lead to the emergence of new power relations and to the further development and change of government practices and technologies.

1.7. Summary

By taking a closer look at Foucault’s idea of governmentality, one can better understand how power functions in a society and how it influences governmental structures. This helps to recognize and examine the complicated and diverse mechanisms of governance.

While governmentality analyzes the theoretical aspects of power in a society, governance concerns the concrete methods and processes that apply and manage this power in practice. Smart governance is a further development of governance that uses modern technologies and digital possibilities to meet current requirements.

2. Corona Crisis: Governance and Biopolitics in a State of Emergency

Global crises often present governments with enormous challenges that require a swift and well-coordinated response. In such situations, the importance of smart governance becomes particularly evident.

An outstanding example of this is the coronavirus pandemic. The analysis of political measures related to COVID-19 provides a concrete example of how smart governance principles are applied. In this process, the theoretical aspects of governmentality are put into practice and validated.

Biopolitics manages and regulates the life of the entire population in all its aspects. Disease is therefore no longer seen as an individual problem, but as a challenge for the community. Dealing with the coronavirus is less about treating individuals and more about regulating the entire population.

[Foucault II: Der Virus und die Biopolitik/-macht]

This involves collecting and centralizing information and statistics, defining relationships and risk assessments and deriving biopolitical regulations from these, such as hygiene measures, quarantine measures, preventive examinations, medication, etc. The regulations for the individual result from these more comprehensive measures, which are scientifically justified by experts, scientists and specialists. They represent the standards by which every individual must measure themselves in order to be accepted as an integral part of the population.

[Über die (Un)Möglichkeiten einer demokratischen Biopolitik]

Biopolitical care follows a doctrine of solidarity. The focus is on the narrative that care for others (whether hygienic or biopsychosocial) also enhances one’s own safety and improves the lives of both the individual and humanity as a whole. From the individual’s perspective, this governance technology appears „like a good shepherd”, whose task is „to do good for those under his watch”.

[Die Covid-19-Pandemie aus biopolitischer Perspektive nach Foucault, p. 217]

With this background knowledge, we now turn to the historic television address by former Chancellor Angela Merkel, which took place on March 18, 2020. In this speech, Merkel addressed the German population to discuss the serious situation of the COVID-19 pandemic and to introduce the government’s measures to contain the virus.

Chancellor Angela Merkel’s speech can serve as a textbook example of how dispositives of power, the link between knowledge and power and biopolitics intertwine in practice:

„Millions of you cannot go to work, your children cannot go to school or daycare, theaters, cinemas, and stores are closed, and perhaps the hardest part: we all miss the interactions that are usually taken for granted. Naturally, each of us is filled with questions and concerns about what happens next in such a situation.“

„I am addressing you today in this unusual manner because I want to tell you what guides me as Chancellor and all my colleagues in the federal government in this situation. This is part of an open democracy: that we make political decisions transparent and explain them. That we justify and communicate our actions as clearly as possible so that they are understandable.“

„It is serious. Take it seriously too. Since German reunification, no, since World War II, there has been no challenge to our country that depends so much on our joint solidarity and action.“

„I would like to explain to you where we currently stand in the epidemic, what the federal government and the state levels are doing to protect everyone in our community and to limit the economic, social and cultural damage. But I would also like to explain to you why you are needed and what each and every individual can do to help.“

„With regard to the epidemic – and everything I am telling you about this comes from the ongoing consultations between the German government and the experts at the Robert Koch Institute and other scientists and virologists: research is being carried out at full speed worldwide, but there is still neither a treatment for the coronavirus nor a vaccine.“

„But everything that could endanger people, everything that could harm the individual but also the community, we have to reduce that now.“

„Now to what is most urgent for me today: all government measures would come to nothing if we did not use the most effective means to prevent the virus from spreading too quickly: And that is ourselves. Just as each and every one of us can be affected by the virus indiscriminately, each and every one of us must now help. First and foremost, by taking seriously what is at stake today. Not to panic, but also not to think for a moment that it doesn’t really depend on him or her. No one is expendable. Everyone counts, it takes an effort from all of us.“

„The virologists‘ advice is clear: no more handshakes, wash your hands thoroughly and often, keep at least one and a half meters away from your neighbours and, ideally, hardly have any contact with the very elderly because they are particularly at risk.“

„I know how difficult what is being asked of us is. We want to be close to each other, especially in times of need. We know affection as physical closeness or touch. But unfortunately, the opposite is true at the moment. And everyone really needs to understand that: At the moment, only distance is an expression of care.“

„Avoiding unnecessary encounters helps everyone who has to deal with more cases in hospitals every day. That’s how we save lives. This will be difficult for many, and it will also depend on leaving no one alone and looking after those who need encouragement and confidence. As families and as a society, we will find other ways to support each other.“

„This is a dynamic situation and we will remain adaptable in it so that we can rethink and react with other instruments at any time. We will explain that too.“

„That’s why I ask you not to believe any rumors, but only the official announcements, which we always have translated into many languages.“

„We are a democracy. We do not live from coercion, but from shared knowledge and participation. This is a historic task and it can only be accomplished together.“

„This means that it will depend not only, but also, on how disciplined everyone is in following and implementing the rules.“

The call to follow scientifically based official communications and not listen to rumors shows that resistance is also expected when implementing the solidarity doctrine. Merkel’s speech illustrates how the government is trying to combat potential resistance and the spread of disinformation by taking control of the flow of information and increasing trust in official channels.

The last two paragraphs quoted activate the social control mechanisms for exercising disciplinary power in democratic societies. The social norm redefined in the speech, combined with moral expectations and peer pressure, is intended to influence and regulate people’s behavior.

In the following months, the so-called AHA+A rules—Distance, Hygiene, Everyday Mask, and App—were seamlessly complemented by the 3G rules: Tested, Recovered, Vaccinated.

As a result, a „hierarchy” of individuals with varying capabilities emerges. Some conform to a certain norm, while others deviate from it. Some can be improved with specific measures, others cannot. For some, certain interventions are effective, while others require different approaches. This categorization of individuals based on their degree of normalcy is one of the major tools of power in contemporary society.

[Die Covid-19-Pandemie aus biopolitischer Perspektive nach Foucault, p. 218]

This results in two complementary biopolitical measures:

a) the promotion of those who are deemed worthy of support,

b) the exclusion of those deemed unworthy of support.

[Die Covid-19-Pandemie aus biopolitischer Perspektive nach Foucault, p. 223]

During an extreme situation such as a pandemic, two key biopolitical governance techniques come to the forefront:

a) „Biopolitical Care within a Solidarity Doctrine“

b) „State Racism“

„State racism” focuses on the elimination of biological threats in order to strengthen the population. The implicit logic is that the more individuals who do not conform to the established norm (in this case, being vaccinated) are eliminated, the fewer degenerates there will be in the population. This will make humanity as a whole better, stronger and more resilient.

[Die Covid-19-Pandemie aus biopolitischer Perspektive nach Foucault, p. 224]

Against this backdrop, the headlines below appear in a different light.

„Corona vaccination is a Christian duty“

Manfred Lütz, Physician and theologian

„The easiest way is to get vaccinated. It’s also the healthiest. I don’t want to have any vaccination certificate forgers as employees, if only because I don’t like employing weirdos. Who knows what other nonsense they believe in.”

Jürgen Kaube, Editor of the FAZ, journalist

„Vaccination opponents are enemies of the state”

Udo Knapp, Political scientist and editor of the taz

„Corona deniers should be consistently assigned to the right-wing extremist spectrum”

Georg Maier (SPD), Thuringia’s Minister of the Interior

„Health insurance doctors demand exclusion of unvaccinated individuals from medical care and psychotherapy”

Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians in Baden-Württemberg

„Access to the store [Food distribution for those in need] is only allowed for those who can provide proof of vaccination or recovery (2G)”

Tante Emma Rodgau e.V., Food distribution for those in need

These are not random and independent events attributable to incompetent or corrupt individuals. Rather, this scenario follows a systematic plan that unfolds as if from a textbook.

Under these conditions, morality is in a sense legally enshrined and thus adopted by the state. The law loses its rational foundation and is instead based on values. Judgments are made in the name of ’solidarity‘.

In his work The Birth of Biopolitics, Foucault writes: „With one hand freedom must be established, but the same action implies that with the other hand one introduces restrictions, controls, constraints, obligations based on threats, and so on”.

[Die Covid-19-Pandemie aus biopolitischer Perspektive nach Foucault, p. 231-232]

Governance in the 20th and 21st centuries operates between two opposing poles: On the one side are the dominant power techniques of the precautionary state, on the other the passive power techniques of liberalism. „Market and plan, invisible or visible hand, central control or self-organization” – the attempts of governance to manage human life economically can be located between these poles.

In the pre-Corona era, governance guided the liberal Western society largely discreetly and with an „invisible” hand. The regulatory mechanisms (norms) were primarily oriented towards self-organization. The majority of the population was considered „normal” and „worthy of support” according to governance standards. People felt comfortable in the „feel-good society” and enjoyed the liberal-democratic order.

These are the same structures, processes and mechanisms that triggered the global pandemic and, in this context, brought dominant power techniques into play more or less overnight. The regulatory mechanisms (norms) were turned around 180 degrees and the precautionary state came to the fore. In this way, democracy became a „democratorship”. The majority of the population adapted to the new regulatory norms (The New Normal) and continued to be considered „normal” and „worthy of support”.

However, a non-negligible minority increasingly had problems complying with the new norms for various reasons and were considered „not worthy of support” in terms of governance. This group of the population experienced social exclusion and slowly began to question the situation. Resistance started to form.

With this biopolitical way of thinking, it becomes understandable how politicians, who had been staunch defenders of democracy for decades, could suddenly become fervent supporters of freedom-restricting measures „without red lines”. This also explains the deep division in society, which even affects families, friends, and acquaintances.

After the regulatory norms shifted during the course of 2023 in connection with the pandemic, those who had previously been excluded were once again classified as „normal”. From a biopolitical perspective, this group transitioned from the „exclusion mode” to the „inclusion mode”.

It feels as though lost freedoms and rights are being restored. There is a sense that the resistance was worthwhile and that one can regain their place in society with dignity. To ensure that a similar situation never happens again, efforts are underway to review and address the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the aim of holding those responsible accountable.

The so-called „RKI Files” deserve special attention. The term „RKI Files” refers to a collection of approximately 2,000 pages of internal protocols from the Corona crisis staff of the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), which were released through a court order. These documents contain detailed records of the meetings and decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic. They help to understand the measures and responses during the pandemic and provide a basis for reviewing and analyzing the decisions made and their impact on society.

On the one hand, these files illustrate the link between knowledge and power as an essential aspect of governmentality and show how scientific findings and political decisions were intertwined. On the other hand, the publication of these protocols has caused a stir, as they clearly show that many of the corona measures were politically and not scientifically motivated.

The measures that have been particularly criticized include lockdowns and mandatory masks. It was revealed that the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) already knew that lockdowns and compulsory masks do more harm than good and that there was insufficient scientific evidence for a general mask requirement. It was recognized that the effectiveness of these measures had been overestimated or misrepresented. The documents suggest that decisions were influenced by political agendas rather than purely scientific assessments.

[What do the RKI-Files really show?]

The documents show that as early as February 2021, health authorities knew that vaccinations did not prevent infections, contrary to public statements at the time. The prevailing narrative suggested that vaccination would protect against severe disease and transmission, which later proved to be a flawed assumption. Despite knowledge of these limitations, the political narrative continued to rely on a broad vaccination campaign with promises of comprehensive protection.

There continued to be concerns about the side effects and long-term risks of the vaccines, which were not fully communicated to the public. The documents indicate that the potential risks were downplayed and the focus was on vaccination as the main tool to manage the pandemic, without sufficient transparency about potential negative effects.

Learning from past experience and optimizing future measures is a central principle of governance. It shows a willingness to respond to criticism, to question and adapt processes. This not only strengthens legitimacy and trust in state institutions, but also increases society’s resilience to future crises. This is in line with Michel Foucault’s view that power and resistance are inextricably linked.

The decision of the courts to allow the publication of the unredacted RKI files can be seen as a step towards more transparency, possibly influenced by public pressure and the need to counter skepticism and mistrust. However, if no political, personal and legal consequences follow, this could be seen as an attempt to stabilize the existing power structure. Transparency without real change channels resistance and legitimizes the existing order.

At the same time, this could be seen as a strategy to neutralize resistance by seemingly taking it seriously but undermining its effectiveness. This can lead to resignation in certain population groups, as the impression is created that resistance is acknowledged but not really taken into account.

Previous reactions from media such as ZDF, Tagesschau and Die WELT indicate that the primary aim is to channel and control criticism and resistance by signaling transparency without, however, allowing any substantial consequences to follow. This approach could be seen as a tactic to maintain trust in governance while leaving the actual power structures untouched.

To what extent the handling of „resistance and counterpower” by governance structures will lead to a change in the status quo remains to be seen in the near future.

Summary:

The analysis of events during the corona pandemic represents a governance crash course that covers all facets of governmentality – from the connection between knowledge and power, through power dispositives and biopolitics, to disciplinary power and the management of resistance and counterpower.

The pandemic has also highlighted how crucial and beneficial digital technologies are for effective governance in crisis situations. It acted as a catalyst by accelerating the adoption and implementation of smart governance practices. For this reason, the pandemic can be understood as a pivotal moment that advanced the development and implementation of smart governance worldwide.

3. One Health Approach – Prevention Through Continuous Governance

While the debates surrounding the RKI files are still ongoing, the next crisis event from the „Disease X” category is slowly approaching – bird flu, which has a zoonotic background and is classified by the WHO as a disease with „pandemic potential”.

And this puts the WHO’s One Health approach on the agenda.

The WHO One Health approach, which sees human, animal and environmental health as inextricably linked, has far-reaching implications for governance. This approach is changing the way governments, organizations and institutions approach and respond to health issues.

Compared to the measures to combat the coronavirus pandemic, the One Health approach is much broader in scope. It requires intersectoral cooperation at both national and international level and requires coordinated governance structures from the healthcare, veterinary, agricultural, food production, environmental and other sectors that enable different authorities and organizations to work together effectively. Globalization of governance structures must ensure that international guidelines and standards are harmonized and effectively implemented.

The knowledge base for defining political decisions and measures is becoming much more complex and involves the integration of knowledge and methods from various scientific disciplines (epidemiology, veterinary medicine, agricultural, food, nutritional and social sciences, etc.).

The integration of environmental health into health strategies requires governance to make environmental sustainability a central component of health strategies.

The focus is on prevention rather than reaction. This changes governance by focusing resources and strategies more on prevention and early warning systems. This includes the monitoring of animal and environmental health and the implementation of early warning systems in these sectors to identify potential health risks to humans at an early stage.

The implementation of the One Health approach requires the adaptation and development of new regulatory frameworks that take into account the interfaces between human, animal and environmental health. Governments must enact new laws and regulations that support these integrative approaches to health and ensure that all relevant sectors work together effectively.

The One Health approach will rely more heavily on smart governance than the coronavirus policy. This is because it requires a comprehensive, preventive and intersectoral approach. Key components are the continuous collection and analysis of data, the integration of different governance structures and the use of modern technologies for monitoring and prevention. These aspects are particularly important in the One Health approach as it moves from a reactive crisis response to a more integrated and preventative governance model.

The One Health approach thus offers a broader perspective and comprehensive tools for policy makers to respond to health crises (human/animal/environment) and take emergency measures where necessary. By emphasizing preventive measures, coordinated responses and international cooperation, the approach helps to strengthen resilience to health risks and minimize the impact of crises on society.

Summary:

„Dangerous epidemics or pandemics therefore have the potential” to intensify the biopolitical transformation of society and „the governmentalization of the modern state described by Foucault by taking measures that clearly go beyond epidemiologically indicated protective measures with the aim of containing the spread of epidemic diseases”.

[Die Covid-19-Pandemie aus biopolitischer Perspektive nach Foucault, p. 233]

In his work, Foucault emphasizes that „the transformations of power that develop and solidify in extreme situations” such as epidemics or pandemics „are not to be regarded as exceptional cases”, „but as the birth and enactment of new universally valid conditions that continue to apply even after the epidemic”. It is about the emergence and consolidation of the new power paradigm and its normalization.

[Foucault: In der Seuche die Disziplinarmacht]

The One Health approach can be seen as an evolution of crisis management, which, through its comprehensive, preventive, and technology-supported nature, forms the basis for the legitimization and lasting implementation of Smart Governance.

4. The Technological Pillars of Smart Governance

In the quest for a simple explanation of the fundamental tools of Smart Governance, one inevitably encounters a statement by Nandan Nilekani, CEO of Infosys Technologies:

„What are the tools of the new world? Everyone should have a digital ID; everyone should have a bank account; everyone should have a smartphone. Then you can do everything. Everything else builds on that.“

Nandan Nilekani

It is worth taking a closer look at the individual elements of his statement.

4.1. The European Digital ID

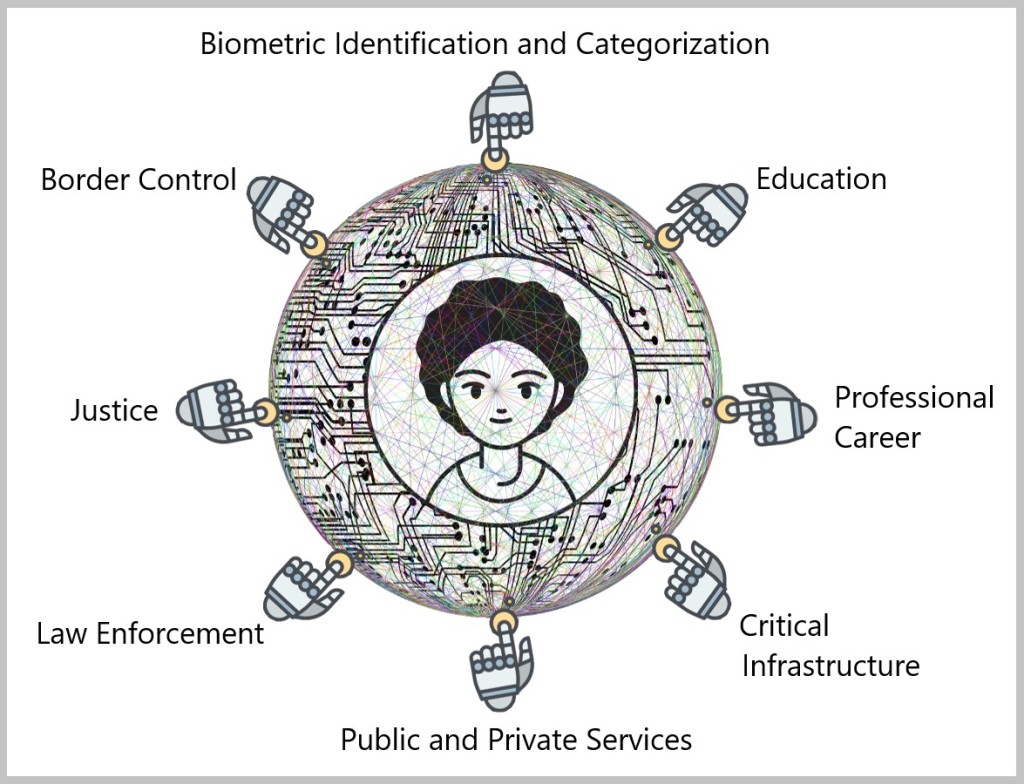

In February 2024, the European Parliament adopted the eIDAS reform (electronic IDentification, Authentication, and trust Services) by a large majority. By fall 2026, all EU member states must offer their citizens a „European Digital Identity Wallet” (ID wallet). This wallet makes it possible to identify oneself both online and offline in almost all areas of life. The EU Commission is aiming for at least 80% of EU citizens to use a digital identity by 2030.

A promotional video from the European Parliament explains that the EU ID Wallet securely stores important information such as official ID cards, documents and bank details in one place. The EU’s digital wallet is designed to make access to public and private services across Europe easier and more efficient. Use of the wallet is voluntary and free of charge. Citizens who decide not to use the digital wallet should not suffer any disadvantages. Wallet users can determine exactly which data is passed on to „trusted parties”. These parties, such as companies or public institutions, must register in the EU member states and specify which data they are requesting and for what purpose.

According to the motto „Trust no politician”, it makes sense to find out about the specific technological implementation of digital identity. In doing so, you quickly come across the French high-tech company THALES, which plays a key role in many state digital projects at government level worldwide.

THALES Group, based in Paris, is a listed company specializing in the following business areas: Defense Industry, Aerospace Technology and Digital Identity and Security. In the field of digital identity and security, THALES has core competencies in the technology segments of biometrics, data security and encryption.

Several large-scale pilot projects will run until 2025 to test the EU digital identity wallet and ensure its secure and smooth roll-out. Around 360 entities are involved in these projects, including private companies and public authorities from 26 Member States as well as Norway, Iceland and Ukraine. Each pilot project is organized as a consortium and brings together expertise from the public and private sectors within the EU. The pilot projects test the EU wallet in various everyday scenarios that Europeans encounter on a daily basis. They also collect feedback on the wallet’s reference implementation. The knowledge gained will be used to improve the security, interoperability and overall design of the EU Digital Identity Wallet.

Under the link eIDAS 2: the countdown to a single European Digital ID Wallet has begun we read:

„Here at Thales, we are ideally positioned to support the key stakeholders responsible for making the EUDI Wallet a reality. As a global leader in trusted digital identity schemes, our teams have worked with governments, public services, and enterprises on eIDAS since its first iteration in 2014.

As a result, we have a range of proven, eIDAS-certified solutions. Now, we partner with dozens of clients across Europe, helping them prepare for eIDAS 2.

Our technology and expertise support the EU and its member states, accelerate the deployment and adoption of the wallet, and help to put greater convenience and security in the hands of millions of EU citizens.“

This promotional video briefly and concisely explains how the eIDAS-certified „Digital ID Wallet” system solution from THALES works in practice.

What is this advertisement subtly trying to convey to us?

We meet the young, attractive woman called Lucy. The name Lucy is often associated with the 2014 action and science fiction film of the same name. In this fictionalized story, 25-year-old student Lucy drastically increases her brain power through a high dose of a drug and begins to use an ever-increasing portion of her „brain capacity”. When she finally reaches 100%, her body merges with all the equipment in a scientific laboratory to form an advanced supercomputer. Lucy travels back in time to the beginnings of the universe and meets her namesake Lucy, who lived around 3.2 million years ago and is often regarded as the link between apes and humans in human evolution.

The choice of this name is intended to appeal to viewers by evoking the idea of enhanced capabilities as well as transformative and ground-breaking features. This emphasizes the uniqueness and innovative nature of the advertised product to attract their attention.

Lucy is also a psychology student. Psychology, also known as the science of the soul, is an empirical science that focuses on describing and explaining human experience and behavior. Psychologists study the experiences, behaviors, and consciousness of people. By highlighting this, the advertisement aims to suggest to the viewer that this „evolutionary” technology is trustworthy.

The Digital Wallet delivers a clear statement right from the start:

„In fact I am a handy way of proving and protecting her identity, both online and face to face. Let us have a closer look at what I can do. I can help governments to better communicate with citizens. Right now I am reminding Lucy of the appointment she needs to schedule for her mandatory vaccination.“

The individual is quickly and personally confronted with a classic biopolitical measure and discreetly reminded to adhere to the prescribed norms. The duty of a responsible citizen is to follow these norms as best as possible, correct abnormal behavior, and ideally avoid it altogether.

In other words, the Digital ID Wallet demonstrates that it is an efficient and cost-effective tool for the government to inform us promptly about regulatory mechanisms (norms) and remind us to comply with them. An example of this is the mandatory vaccination. This, of course, assumes that the government is well-informed about our electronic health records. This will soon be ensured by the so-called Health Digital Agency Act (GDAG).

The German Health Minister Karl Lauterbach summarizes the draft law in his X-post as follows:

Back in 2020, the THALES promotional film illustrated the connection between the digital ID wallet and the electronic patient record when visiting the doctor. This seems to be pioneering for some government measures in 2024.

The digital wallet also controls communication with all state authorities and enables access to financial and mobility services. The digital ID wallet is not only used for access to the state exam, but also for access to the pub.

„Yes, I am Lucy´s best companion. I protect her identity and official credentials wherever she goes. I provide secured access to public and private services and allow her to have full control over her data privacy. In other words, I give the right access to the right data to the right person. I am also trusted by governments to best support countries digital transformation.“

For the viewer, the Digital ID Wallet appears as the digital form of the „‘good shepherd’, whose task it is to ‘do good to those over whom one watches’”.

In combination with the European Digital Identity, the smartphone is transformed into a specific, technical instrument for implementing government techniques to monitor and control both collectives and individuals. This implementation has two dimensions:

a) political dimension

Defined security and precautionary rules function as a control mechanism for the population, aiming to detect dangers and exert influence as broadly as possible on the behaviors of population and free (collective) subjects. For instance, in addition to pandemics, climate change is increasingly being defined as a risk situation.

b) entrepreneurial-economic dimension

The smartphone has become an everyday companion and generates countless amounts of data. Companies use this data to predict aspects such as purchasing behavior and lifestyle habits. They use comprehensive measures to influence the lives of both the population and individuals.

The political dimension of surveillance and control is ‚visible‘. It is usually carried out in a „hard Go-NoGo” manner. In the event of non-compliance with the specified standards, consequences follow immediately (from exclusion to more far-reaching disciplinary measures). Roughly speaking, by using the Digital ID Wallet and its associated access to biometric data, one is fraud-proof transparent! And if one doesn’t meet the norms set by the ‚good shepherd‘, one could end up naked when the going gets tough. This brings back memories for some critics of the government’s coronavirus policy.

The entrepreneurial-economic dimension operates in a more subtle, ‚invisible,‘ and discreet manner. It promotes ideals and norms, focusing on encouraging those who adhere to these norms.

THALES has also created a suitable promotional video for this dimension entitled „Trusted digital lives”.

The promotional story suggests limitless fun and convenience when digitizing one’s life. The key to this paradise is the digital capture of biometric data and its constant connection to one’s movement and behavior profile.

According to the logic of Michel Foucault, the inventor of the terms ‚biopolitics‘ and ‚governmentality‘, the goal, in addition to maintaining/establishing a global state of equilibrium, is the security of the whole and its protection from internal dangers. As the population is diverse, it is a matter of recognizing the dangers on the one hand and finding a form of government that is so far-reaching that it is effective even in the most hidden corners of the population on the other. „To govern the population is to govern its global findings; to govern the population is to govern it in depth, in subtlety and in detail.“

[The (in)visible ‚friend‘, p. 31]

The establishment of a culture where the smartphone is used as an extension of one’s own person opens up entirely new possibilities for the organization and management of societies. With the introduction of the European Digital Identity, each individual can be securely identified and addressed in digital systems. This reduces our behavior to logical-mathematical processes, which are continuously optimized based on the data collected.

4.2. Technological Self-management as the Foundation of Smart Governance

„It is so easy to be immature. If I have a book to serve as my understanding, a pastor to serve as my conscience, a physician to determine my diet for me, and so on, I need not exert myself at all. I need not think, if only I can pay: others will readily undertake the irksome work for me.“

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804), German Philosopher

It was predicted 10 years ago that the era of personal computing, represented by desktop computers and laptops, would give way to the era of intimate computing. It was predicted that even before 2020, „intimate devices”, environments and networks would know a great deal about us.

A vivid example of this development is the Humane AI PIN from Humane, a start-up company founded by former Apple employees that now receives support from prominent investors such as Sam Altman, Microsoft, Qualcomm Ventures and other well-known investors.

This innovative gadget caused a global stir just days after its announcement in the media and is already being hailed as the next „game changer” after the smartphone.

At first glance, the advertising for the Humane AI PIN seems very convincing.

The era of intimate computing has now become a reality, as Imran Chaudhri, CEO of Humane, explained in his visionary speech „The Disappearing Computer” during the TED conference in April 2023. It is worth watching this speech in full.

Let’s take a look at some of the statements made by the Californian visionary:

„In the future, technology will be both ambient (i.e. adapted to the environment) and contextual (i.e. adapted to the situation). And that means you need to use AI to really understand yourself and your environment to get the best results.“

„And we gain this context through machine learning. The more you use our AI-powered device, the better WE can help you in any emergency situation. Your AI effectively becomes a constantly evolving, personalized form of memory. And WE think that’s great.“

„Your AI finds out what you need at the speed of thought. A feeling that will continue to evolve as technology advances. … As AI advances, WE will see it change almost every aspect of our lives. In ways that seem unimaginable right now. In fact, Sam Altman of OpenAI feels the same way we do – AI is vastly underestimated. And I’ll add, as long as WE get it right. WE truly believe that WE are just beginning to scratch the surface of what is possible.“

„More human, more intuitive interactions that are screenless, seamless and tangible – that is the possibility of rethinking the human-technology relationship as WE know it. And that’s the exciting thing. It is undoubtedly a great challenge. But it is the world WE want to live in. A world where technology not only helps us get back into the world, but also enhances our ability to do so. It is within reach.“

„In the future, the technology could be almost invisible.“

These statements reflect the principles of neoliberal governmentality by emphasizing the individual’s responsibility to use and adapt to new technologies, promoting a culture of constant self-improvement and presenting technological control as a means of regulating and optimizing life. New norms and values are created through technological innovation. In this world, technology is not only useful but also enhances human capabilities, setting new standards for performance and efficiency.

Neoliberal governmentality relies on digital surveillance. Without the data generated by digital surveillance, the system would collapse; they are its raw material and currency. Innovative gadgets, such as the Humane AI PIN, present themselves as efficient tools in efforts to discipline, control, and optimize the postmodern individual. They focus their attention on the individual with all its desires, ambitions, potentials, and weaknesses. It appears as though they are available to the individual to assist in becoming an improved and more successful self.

In this process, the subtly deployed „Technologies of the Self”, as defined by Foucault, come into play. These are processes and practices that enable individuals, either independently or with the support of others, to carry out a variety of operations on their body, soul, thinking, behavior, and way of life.

According to Foucault, the „Technologies of the Self” always require a relationship to the other: „One cannot deal with oneself without having a relationship to the other.” [Foucault, Michel: Die Regierung des Selbst und der anderen. Vorlesung am Collège de France 1982/83. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 2009]

The function of the Other is to speak the truth, especially unpleasant truths, which should encourage the subject to reflect on their actions and modify them if necessary.

The following dialog sequence between the CEO of Humane and the artificial intelligence illustrates the practical application of these power techniques.

Above all, the technologies of the self are based on the subject’s free decision to work on himself and, by confessing his „sins” or „mistakes”, to open himself up to spiritual guidance and then to receive instructions or teachings.

In Foucault’s philosophy of power, the subjugated subject and the autonomous self are two sides of the same phenomenon. When dealing with wearables in the context of the omnipresent data economy, the modern indifferent subject comes to the fore. On the one hand, it acts autonomously, actively and creatively and is aware of the risks and dangers of data mining. On the other hand, it bows to the principles of data production and takes no care to protect its own privacy. In this way, postmodern (supposed) concern for oneself results in self-neglect.

The subject-object of self-measurement through wearables does not surrender out of cowardice (without fear of action or decisions) but due to convenience, disinterest, and a misguided assessment (‚I have nothing to hide‘) of its immaturity. Submission to the regime of self-optimization relieves the subject from independent thinking and self-care. It continuously receives user-friendly feedback and a preconceived interpretation of itself, freeing it from the obligation to reflect and contemplate. Self-awareness through data shapes a data-dependent subject – one that admits to being unable or unwilling to independently think about itself without wearables, delegating this form of self-work to a medium. In doing so, the subject becomes alienated from itself, especially from its own body, which becomes a foreign object translated into data streams. Despite the claim to enlightenment and supposed emancipation, this results in a flexibilized, self-marketing, fundamentally indifferent subject trapped in the subtle entanglements of digital pastoral power.

Smartphones and wearables are becoming personal laboratories and promise to empower us all. These devices are evolving into advisors: they not only monitor our activities, but also give specific instructions and recommendations. The design of wearables influences our decisions, often unconsciously, by presenting different options. Users are guided towards certain behaviors through targeted nudging. In this way, wearables contribute to social control and convey general norms.

Seen in this light, the visionary speech by Imran Chaudhri, the CEO of Humane, takes on a different perspective.

The Israeli historian, Yuval Harari, gets more specific in this regard. During his ‚pathetic‘ appearance at the Frontiers Forum in May 2023 on the topic „AI and the future of humanity“, he outlines the following vision of the future:

„But the longer we talk to the bot, the better it gets to know us and understands how to refine its messages to manipulate our political views or our economic views or anything else. As I said, by mastering language, AI can build intimate relationships with humans and use the power of intimacy to influence our opinions.“

„New AI tools would have an immense impact on human opinions and our view of the world. For example, people could come to use a single AI advisor as the one-stop oracle and source of all the information they need.“

„People and companies that control the new AI oracles will be extremely powerful.“

Technological self-management and smart governance reinforce each other by using common principles and technologies to optimize both individual behavior and the management and governance of societies. Both concepts promote efficiency, transparency and personalized interactions through data-based decision making and behavior-guiding techniques. This symbiosis enables targeted changes on an individual and societal level.

Smart governance promotes the decentralization and privatization of public services. Technological solutions that enable more efficient management of public services are often provided by private actors. This takes place within the framework of public-private partnerships or through the direct outsourcing of services to private companies.

4.3. Digital Twins as the Basis for Smart Governance Strategies

What would you do if you had a digital copy of yourself? A digital twin that is just like you and lives in an exact digital representation of your home, workplace or city? Even better, what if this digital twin couldn’t feel pain or injury? The possibilities would be incredible. You could make decisions without fear of the consequences and with much more certainty about the outcome.

The management consultancy McKinsey describes the term „digital twin” as follows:

„A digital twin is a digital representation of a physical object, person, or process, contextualized in a digital version of its environment. Digital twins can help an organization simulate real situations and their outcomes, ultimately allowing it to make better decisions.“

Is it already possible to create a virtual copy of an entire city? Yes, this is already feasible. The Siemensstadt Square project is just one example of this.

Digital twins act as a central platform for integrating and coordinating various smart technologies. They bundle data from IoT devices, sensors and other digital systems to create a comprehensive picture of the urban environment. This allows planners to test different scenarios and measure their results without affecting the city and its residents. Working solutions can then be implemented in the physical space.

Digital twins are an indispensable tool for smart governance, as they offer numerous advantages and can significantly improve the efficiency and effectiveness of administration. This technology enables precise real-time data analysis and the simulation of various scenarios. As a result, potential problems can be identified at an early stage and suitable measures planned before they manifest themselves in the real world. The possible applications are diverse: from monitoring and maintaining infrastructure to analyzing environmental data and social dynamics to crisis management in the event of natural disasters or pandemics.

Digital twins are detailed replicas of systems that are designed for a two-way flow of information with the real object. They enable a bidirectional exchange of real-time data and contribute to a better understanding of what is currently happening. This allows problems to be resolved in real time and the performance of the real object to be optimized.

If a digital twin can successfully emulate an entire district, could it then be extended to the individual level to function as a personal digital twin?

Many experts are convinced that this vision is achievable, and indeed, some of them are already working on highly ambitious applications. The assessment suggests that personal digital twins could become an everyday reality by the end of the decade – with significant impetus coming from the healthcare sector.

Former CEO of General Electric, Bill Ruh, for instance, predicts that every person will be equipped with a digital twin from birth. This digital twin will leverage the individual’s genome to provide personalized treatment recommendations as soon as diseases occur.

The fact that the Personal Digital Twin is more than just a vision is demonstrated by the circumstance that in 2020, the European Commission’s Joint Research Center (JRC) launched the project „MyDigitalTwin: Trusted Personal Digital Twins in a Transformed Society”. The information available on the Internet about this project is sparse. This link provides the following general information:

„MyDigitalTwin (MyDT) project aims to study how to utilize, supervise, and control the rapidly growing generation of personal data via PDTs, and PDT role in understanding complex/fast societal dynamics. The study wants to explore the challenges related to ethics and privacy, and the opportunities to move the existing PDT frameworks from a Business–to–Customer (B2C) to a Government–to–Citizen (G2C) context. Finally, MyDT will consider the PDT role for a European e–Identity.“

Further information on the EU Commission’s MyDigitalTwin (MyDT) project can be found in the eBook by Prof. Roberto Saracco entitled „Personal Digital Twins – A third evolution step of humankind?”. Prof. Saracco is not only one of the chairs of the IEEE Digital Reality Initiative, but also an active participant in the expert working group of the MyDT project.

To what extent should the PDT reflect the physical person?

This essentially depends on what is expected from the PDT. Currently, the use of PDTs is advocated in healthcare. A PDT designed for such a purpose would reflect physiological aspects of the person with a multitude of details (weight, height, gender, heartbeats, respiratory rate, metabolism, etc.) and may encompass various other health-related data (genome sequence, allergies, living environment, parental pathologies, occupational risks, etc.).

This promotional video „Forward CarePod™, the World’s First AI Doctor’s Office” by the US company GoForward demonstrates how quickly this can now be implemented in practice.

Google recently unveiled MedLM, a series of specialized generative AI models for the healthcare sector. According to Google, the performance of these AI models is equivalent to that of a medical specialist.

With the promise of personal 360-degree comprehensive health protection around the clock, 365 days a year, the majority of the population will voluntarily take the first step towards a Personal Digital Twin (PDT).

A large amount of personal data sets are obviously crucial for the operation of the PDT; a PDT without data does not exist. The article „The last bastion – The human body as a technology platform” provides an up-to-date overview of how this data is collected and processed technologically.

In this constellation, the basis of trust between the natural person and the institution that collects and manages the personal data records is essential.

For this reason, the European Union (EU) has introduced regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the ‚EU Data Act.‘ While the ‚EU Data Act‘ aims to make more data available for societal and economic purposes, the GDPR focuses on the protection of personal data and the rights of individuals. These regulations address different needs: data protection and confidentiality on one hand, and data use and sharing on the other.

This creates potential conflict. A harmonious alignment of the requirements of both regulations requires careful consideration to ensure that the objectives of the free flow of data and data protection are reconciled. And that is a real challenge for smart governance.